As faith grows in the transformational possibilities of artificial intelligence, a huge stock market bubble seems to be forming. The potential overvaluation of shares may run to trillions of dollars, threatening devastating economic consequences when it bursts – as bubbles inevitably do.

This is hardly unprecedented. From tulip mania and the South Sea Company onwards, frothy markets have formed and collapsed, particularly in periods of economic change – none more notable nor perhaps misunderstood than the Wall Street bubble and crash of 1929.

In his groundbreaking book The Great Crash, the economist JK Galbraith called “Black Tuesday”, 29 October that year, “the most devastating day in the history of the New York stock market, and it may have been the most devastating day in the history of markets.”

Seven decades after Galbraith, Andrew Ross Sorkin has returned to the scene of that catastrophe to find “remarkable parallels between that era and today’s political and economic climate”. These include rapid innovation: now in AI; then through the mass production of desirable consumer durables, from cars and radios to dishwashers. These made millionaires and celebrities of the corporate bosses and Wall Street titans who bet on them. But behind the upbeat Roaring 20s headlines, Sorkin notes, it also created “a set of underlying imbalances, a massive bifurcation of American society”. Then, as now, businessmen played politics and became statesmen – including Thomas Lamont, the sophisticated de facto head of JP Morgan, who shuttled between America and Europe to negotiate German reparations for the first world war, before turning to help the government deal with the aftermath of a crash his bank had helped to bring about.

Other parallels include a fierce debate over the role of the Federal Reserve (an institution then in its infancy, which was accused – as it is now – of straying beyond its narrow legal mandate) and a country deeply divided over the role of the state, as the laissez-faire Republican Calvin Coolidge was followed into the White House by the cautiously technocratic Herbert Hoover and then Democrat New Dealer Franklin D Roosevelt. It was Hoover who unwisely reframed the 1929 crash from a market panic into a depression, helping embed a pessimistic state of mind in the American people that it took over a decade and another world war to shake off.

Above all, there was an abundance of credit available in the late 1920s, allowing the rich and middle-earning members of the public alike to borrow heavily to buy “on margin” shares, whose value they believed was destined always to go up. Debt is the “almost singular through line behind every major financial crisis”, explains Sorkin – which is why recent explosions in the private credit markets have set alarm bells ringing today.

Churchill’s own losses were to take him to the edge of bankruptcy, where he remained until becoming prime minister

Churchill’s own losses were to take him to the edge of bankruptcy, where he remained until becoming prime minister

Whereas Galbraith saw the crash through the lens of economics, Sorkin comes at it as a scoop-driven storytelling business journalist, of which he is one of the best. Having written the definitive fly-on-the-wall account of the financial crisis of 2008, Too Big to Fail, and co-created the hit hedge fund television melodrama Billions, Sorkin is again strong on character, drama and narrative, bringing events and long-dead personalities to life in all their complexity and colour.

Sorkin’s choice of main character is Charles Mitchell, head of National City Bank, whose unfailing optimism earned him the nickname “Sunshine Charlie”. As he struggles to save a merger that would have created the world’s biggest financial institution, he takes out a huge personal loan to buy shares in the bank in a failed effort to support its tumbling share price. Later, widely seen as the villain behind the crash, he is prosecuted for tax evasion only (spoiler alert) to be unexpectedly acquitted.

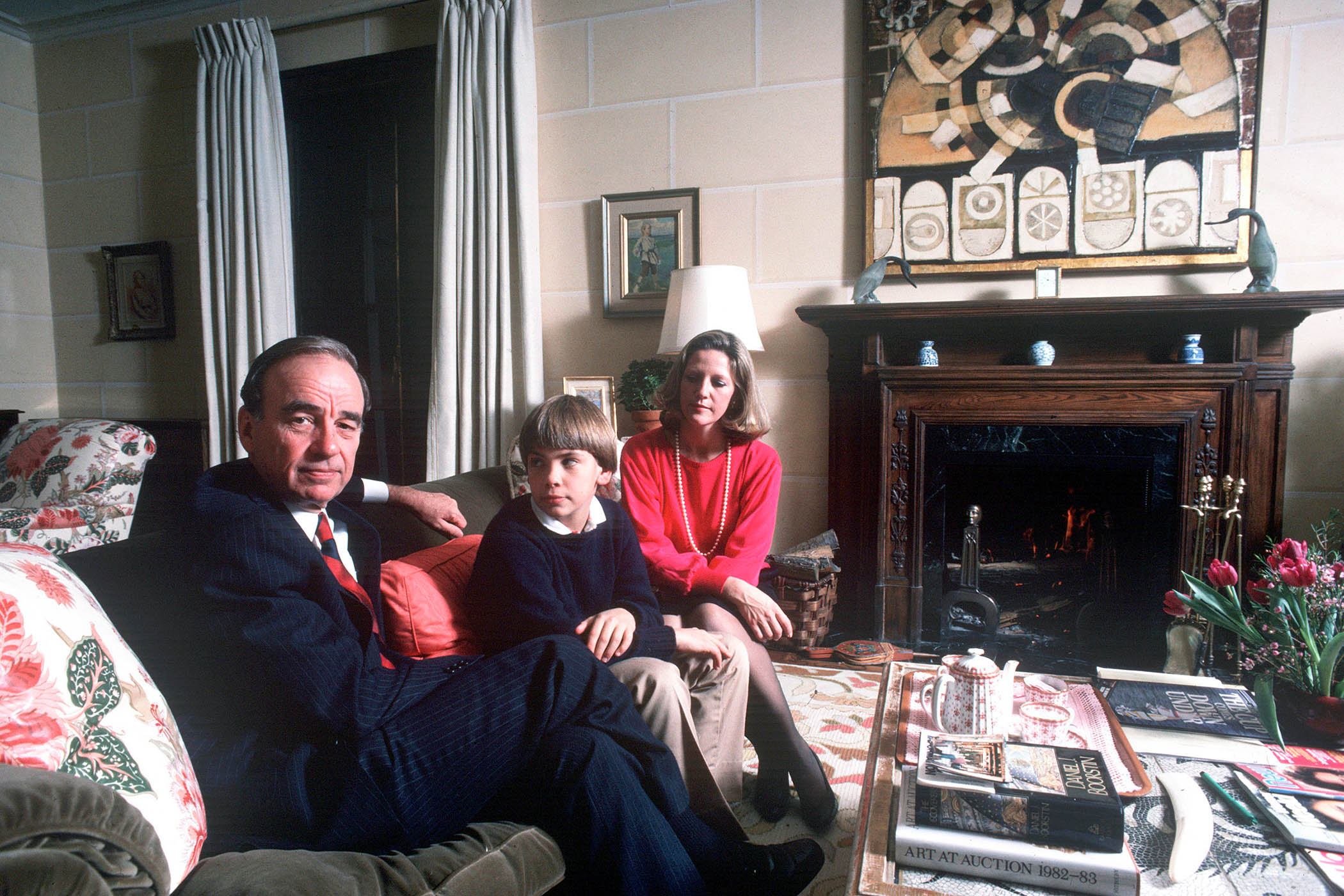

But the potboiler story of 1929 contains an entire repertory of compelling characters. Many, like Mitchell, tried to maintain their public reputations for probity while privately – and, in some cases, illegally – acting in their own interests, as market conditions worsened. There’s Lamont, playing the Jamie Dimon financial saviour role while failing to stop a secret Rockefeller initiative to break up the House of Morgan. The short-seller Jesse Livermore, who made a fortune betting on lower prices on Black Tuesday, only to return home to a wife convinced they were financially ruined and ready to sell her art and jewellery. The crusty old senator Carter Glass, who couldn’t stand congressman Henry Steagall, though they co-sponsored (and gave their names to) the main legislation to repair the financial system after the crash. And the legendary investor Bernard Baruch, who hosts a grand dinner party for Winston Churchill at his mansion on the eve of the crash, attended by Mitchell.

Churchill, who some blame for creating the easy money era in the US when he was chancellor by returning the pound to the gold standard, had become addicted to debt-fuelled share trading during a grand tour of America in the summer of 1929. His eventual losses were to take him to the edge of bankruptcy, where he remained until becoming prime minister. Staying at the Plaza hotel as the crisis took effect, Churchill wrote of witnessing a “gentleman cast himself down 15 storeys” who “was dashed to pieces”, but Sorkin notes that the great statesman didn’t seem unduly troubled by the broader ramifications of the crash. “The English critic would do well to acquaint himself with the inherent probity and strength of the American speculative machine,” Churchill cautioned. “It is not built to prevent crises, but to survive them.” We may soon find out if that remains the case.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

1929: The Inside Story of the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History by Andrew Ross Sorkin is published by Allen Lane (£30). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £27. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photograph by Martin McEvilly/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images