Family photographs courtesy of Geoff Dyer

When I say, truthfully, that I have no memory of the picture being taken I’m conscious that this is meaningless because, of course, the photograph is memory. I have no idea who took the picture. As a result, and because it includes all three of us – it’s not like there was an older brother or sister who, by taking the picture, rendered it incomplete because of their absence – something strange happens.

We’ve clearly just parked the car, in a car park with few cars as was the norm back in the days before traffic. The relative brevity of the number plate – 3489 AD, the first number I ever memorised – attests to that. AD identifies it as a vehicle bought in Gloucestershire but it was a source of pleasure to my dad because they were his initials – Arthur Dyer – even though everyone called him Jack or John. I prefer to think of the number plate as offering a kind of internal dating, AD 3489, as if this image from the past were a sci-fi projection – obsolete and erroneous as these things often turn out to be – of what the future might one day look like.

The bus in the background hints at a less distant future in the form of the raves and festivals – Tribal Gathering, Pendragon – I went to in the 1990s, though there is no indication as to what kind of gathering this might have been. Again, the absence of evidence suggests that back in this uncongested golden age of British motoring, the car park was the festival.

It may seem equally bizarre that my dad’s sweater is tucked into his trousers but since he tucked his shirt into his underpants an internally layered logic is at work. That red sweater (never as red as it looks here, more rust-coloured) and my blue one would have been knitted by my mum. I grew out of mine but eventually grew into his, wearing it – untucked – well into my 20s. (By the 1980s, the technology of film had changed so that the red dulled into literal truth, never again achieving the fictive bloom recorded here.)

Girls made up half the population of the world – except in Cheltenham, where the figure seemed to have dwindled to 10%

Girls made up half the population of the world – except in Cheltenham, where the figure seemed to have dwindled to 10%

My parents were, as my mum used to say, good with their hands, though his left hand looks rather odd, like a three-fingered, flesh-coloured glove. My mum is covering up her right wrist with her left hand. She always did this. For now consider the grumpy little fella in the cowboy hat. You can tell he’s an only child by the way he’s so attached to his inflatable companion – so adorable as to render any doubts about its species irrelevant. On another of our Sunday excursions into the Cotswolds I sang, over and over, a song about a cowboy and his horse called Old Faithful, how they roamed the range together in all kinds of weather, and how they looked forward to sharing their retirement years together, when they were put out to pasture, after their round-up days were over.

Sickness

That I was such a sickly child – dreadful eczema, bandaged fingers covered in warts, constantly off school with colds and the numerous other illnesses that childhood is heir to – meant that my parents were always taking me to see either Dr Bracey or Dr Wingate at their surgery on Cheltenham’s Leckhampton Road, a five-minute walk from home, straight up Fairfield Avenue.

We went there once because, my dad told Dr Bracey, I was having trouble with my “toy-oy”.

“What?” snapped Doc Bracey.

“His penis,” my dad confessed under this first bit of cross-examination.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

It pained him to say this, though on reflection it seems strange that his preferred term was toy-oy since my parents tried to instill in me the belief that it was wrong to play with myself. (If only I’d had the wit back then to ask: “What am I supposed to do with a toy-oy except play-ay with it?”) It was around this time, during one of our war games, that I began imitating the speech of a Japanese officer by saying: “Ah, so…” Nowadays people might say that this was the oral equivalent of pulling one’s face into a slanty-eyed expression, but my dad’s objection, while no less vehement, was quite different – and somewhat bewildering. I must not say that, must not say “Ah, so,” because it sounded like a “very rude word”, so rude that he wouldn’t even reveal what it was.

Swimming

My parents could not swim. So they were full of admiration for Mr Grinnell, a teacher dedicated to making sure that every kid at Naunton Park acquired this skill at the earliest possible age. Once a week a battered double-decker bus transported us from school to Alstone Baths. These baths bore roughly the same relation to pools at upmarket health clubs that the Victorian workhouse does to a luxury hotel. Alstone Baths opened in 1887 and were, by the 1960s, in an advanced state of disrepair. The clangy, heavily chlorinated acoustic amplified this tale of decline but we did all learn to swim. At a less than uniform pace we progressed from water-winged doggie paddle to a width and then a length (for which a certificate was issued), but the real proof of our increasing aquatic adaptation came in the form of the foot badge known as a verruca.

En route from the wet changing rooms to the pool itself we had to step through disinfectant footbaths intended to prevent the spread of verrucas but it was difficult to avoid the suspicion that this was where we caught them. They were like little aquariums, those footbaths, invisibly swimming with verrucas. Visible horror, on the tiled floors of the changing rooms, came in the form of pink sticking plasters that had floated off raw heels and toes, and water-bloated cigarette ends. Though they were a source of intense pain, it’s difficult, now, not to feel a certain fondness for the verruca as the municipal sole of the welfare state.

Sweet treats

My childhood was saturated in sugar. I loved sugar on and in everything: Corn Flakes, Weetabix and porridge (Quaker Oats and Scott’s oats), obviously, but also bread and butter, tomatoes, raspberries. Fizzy drinks (Corona). Heaped spoons of sugar in tea and coffee (tainted, always, by the crinkled skin that formed on the surface and had to be delicately removed). All forms of Cadbury’s chocolate. Lucozade. Sugar and sugar-drenched jam in semolina. Sugary rice pudding. Sugar anything. So thoroughly did sugar permeate everything I ate – even, slightly later, yoghurt, the first suggestion of what would later come under the heading “healthy eating” – that I was not even conscious of sweetness, only of its intolerable absence. Nothing was ever too sweet – how could it be? – though certain things inevitably required more sugar (rhubarb: a multi-tablespoon dumping) than others (strawberries: a single teaspoon sprinkle).

It wasn’t that I had a sweet tooth; I had a normal tooth, a tooth that craved sugar. Far from discouraging this fondness for sugar, my parents instilled and then endorsed it by their own gradually increasing sugar intake, their absolute abhorrence of – more a kind of astonishment about – anything lacking in sugar. Tea without sugar was not just horrible to them; it was practically an abuse of their human rights.

The assumption was that nothing really tasted of anything because the only taste that counted – the only requirement – was sweetness, sugariness. I must not exaggerate. We did not put sugar on chocolates or sweets, did not add sugar to Corona (pop) or Kellogg’s sugar-coated Frosties, or the aptly named Sugar Puffs, because they were already so loaded with sugar, it would have been impossible to make them taste more sugary. These were not drinks or food with sugar added; they were sugars in liquid or cereal form. Everything else cried out for sugar.

Sugar, lovely sugar! Not the cause of obesity and harbinger of diabetes as we now think of it, but a source of pleasure, nutrition, energy and happiness. We are talking exclusively of white sugar. Even brown sugar was too sophisticated; an acquired taste with suggestions of a health fad, it was practically muesli or brown rice in granular form. My parents took pride in the way that we didn’t eat sliced bread, never bought those limp packets of Mothers Pride, but it was always white bread that we prided ourselves on buying and slicing (though I was never allowed to cut it myself for fear that I might amputate a thumb), white bread that formed the basis of my favourite sandwiches: sugar sandwiches, loaded and crunchy with white sugar.

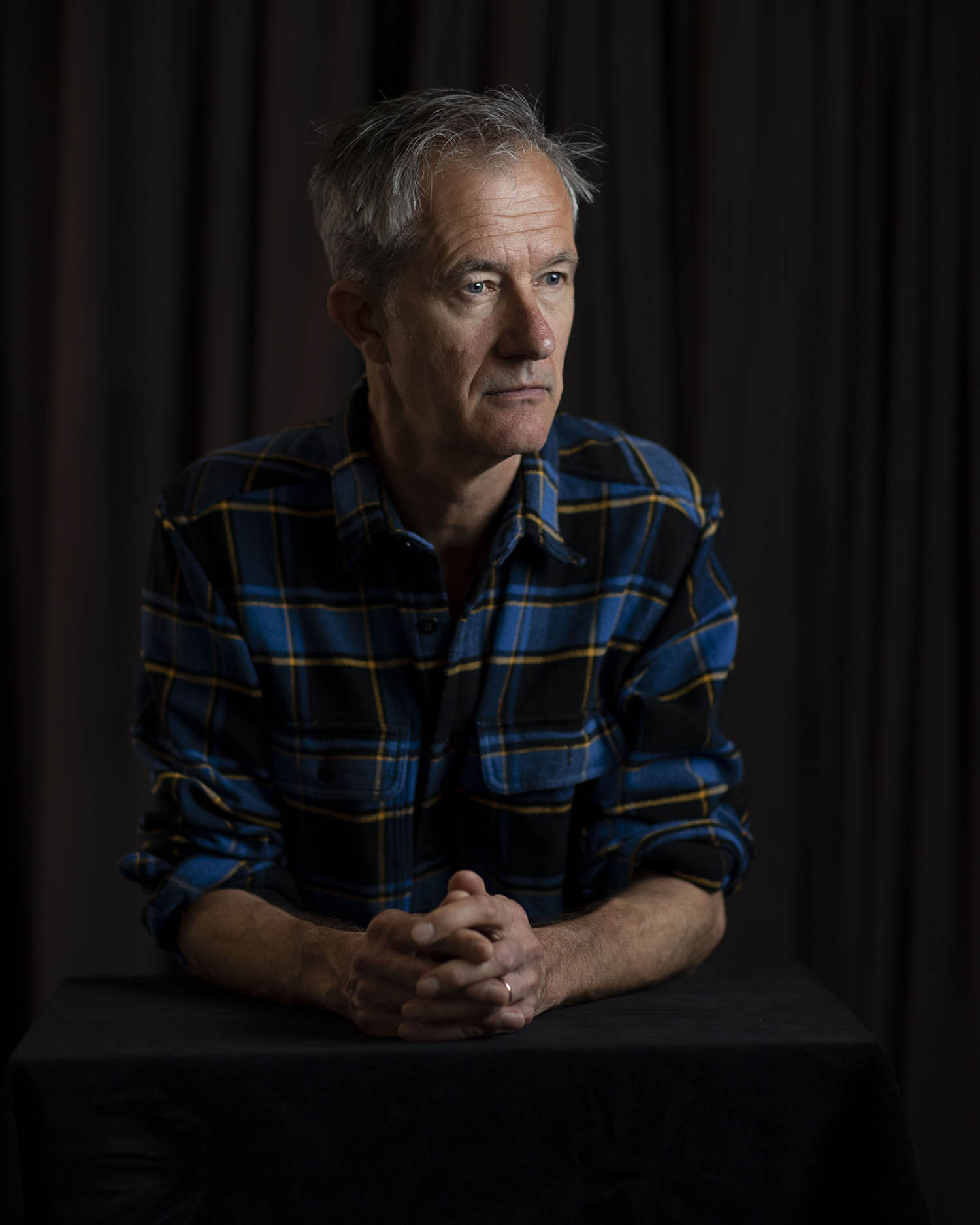

And the extraordinary thing? It did us no harm! My mum and dad lived to 85 and 90 respectively and for the last 20 years of their long lives the tea they drank was so dense with sugar it was more like a thick, highly sweetened brown sludge than a drink. Have I got diabetes? Have I turned into a fat slob, a fat anything? Look at me: whippet-thin, fiddle-fit and raised almost exclusively on a diet of white sugar.

Girls

Talking to girls meant one thing back then: chatting them up, a skill so mysterious no one had any idea how or where one might set about acquiring it. Being at a single-sex school, without sisters whose friends I may have met, meant I had no casual contact with girls, no experience of getting used to them; I lacked grammar and vocabulary, every component that made communication possible.

Still, whenever I saw these two sisters, I’d pull over and try to think of something to say. In the cumulative awkwardness of one of these non-chats, the older of the two, the one I liked, with long dark hair, mentioned that she knew another boy from the grammar school, Pierre Laprade, who, along with Myles, was one of the bad boys in our year. In response to this unwelcome news, the only thing I could think to say was: “I like competition.”

After delivering this line I pedalled off, pleased to have swaggered spontaneously into the linguistic realm of chat-up. It took less than 24 hours for news of this declaration to be conveyed to Laprade and his friend, the slightly scary Martin, who did weightlifting. (If a fight was simmering between Martin and an opponent, onlookers would encourage Martin to “Pick him up.” Obviously there were worse things that could happen. Better to get lifted off your feet than have your head duffed in, but the knowledge that he was capable of doing this filled everyone with dread because it was obvious that you could, at any moment, be flung to the floor.) For the next several days, every time I saw Laprade and Martin at school, one of them would say: “He likes competition.”

Except I didn’t. Another linguistic shortcoming: I didn’t know the word “mortifying”. But I didn’t need to know the word to experience everything that it meant. From then on I sulked past the smirking convent girls without a word.

School dinners

The dinners at junior school had been inedibly horrible. This proved good preparation for grammar school, where they were every bit as horrible. During one meal, I tried to swallow a piece of meat – more like two blobs of meat connected, like weights on a bar, by a length of gristle. One lump was halfway down my throat, the other was still in my mouth. Faced with a choice I had no time to make – chew and swallow the latter or get the former back up into my mouth – the outcome was to gag.

I did like some things – it’s just that I didn’t like most things. My parents alternated between trying to make me eat and resigning themselves to the conclusion that “If he was hungry he’d eat”: another instance of the way that everyday life was measured against a baseline of survival and subsistence. The opposite of Oliver Twist, I was always wanting either less or, ideally, none at all. How did I survive given that I ate and drank nothing before cycling home where I’d have a glass of squash before my mum served some slop for tea that was marginally less horrible than the slop we’d been served for dinner (lunch)? Those school meals! Toad-in-the-hole: sausages – made entirely of fat – served in batter. Grey lamb – nothing but fat and gristle – with mashed potatoes that were watery and lumpy. Pale, wilted chips. Evaporated carrots, swamp-boiled cabbage. Stink-fish on Fridays. Worst of all was the veiny liver, a dense concentrate of horror in appearance, texture, colour and smell.

I haven’t included "taste” in this list of charges because there was none. I don’t mean it was lacking in taste; I bet it wasn’t, am sure it packed a punch, but I never got that far, never actually tasted it. The smell of all the food was disgusting and this smell, congealed and lingering, contaminated the school, from the time it was being prepared in the morning to the afternoons when the remains of one day’s slop were being disposed of and the kitchens cleaned prior to the preparation of the next day’s slop.

The smell of food typically makes one hungry but this miasma of frying fat, of vegetables boiled to extinction, made me dread the prospect of eating. I’d really like to see that slop now, have it transported from the past and properly examined by someone from the Jamie Oliver Ministry of Food. It would fall below every EU-established standard of what is fit for human and possibly even animal consumption.

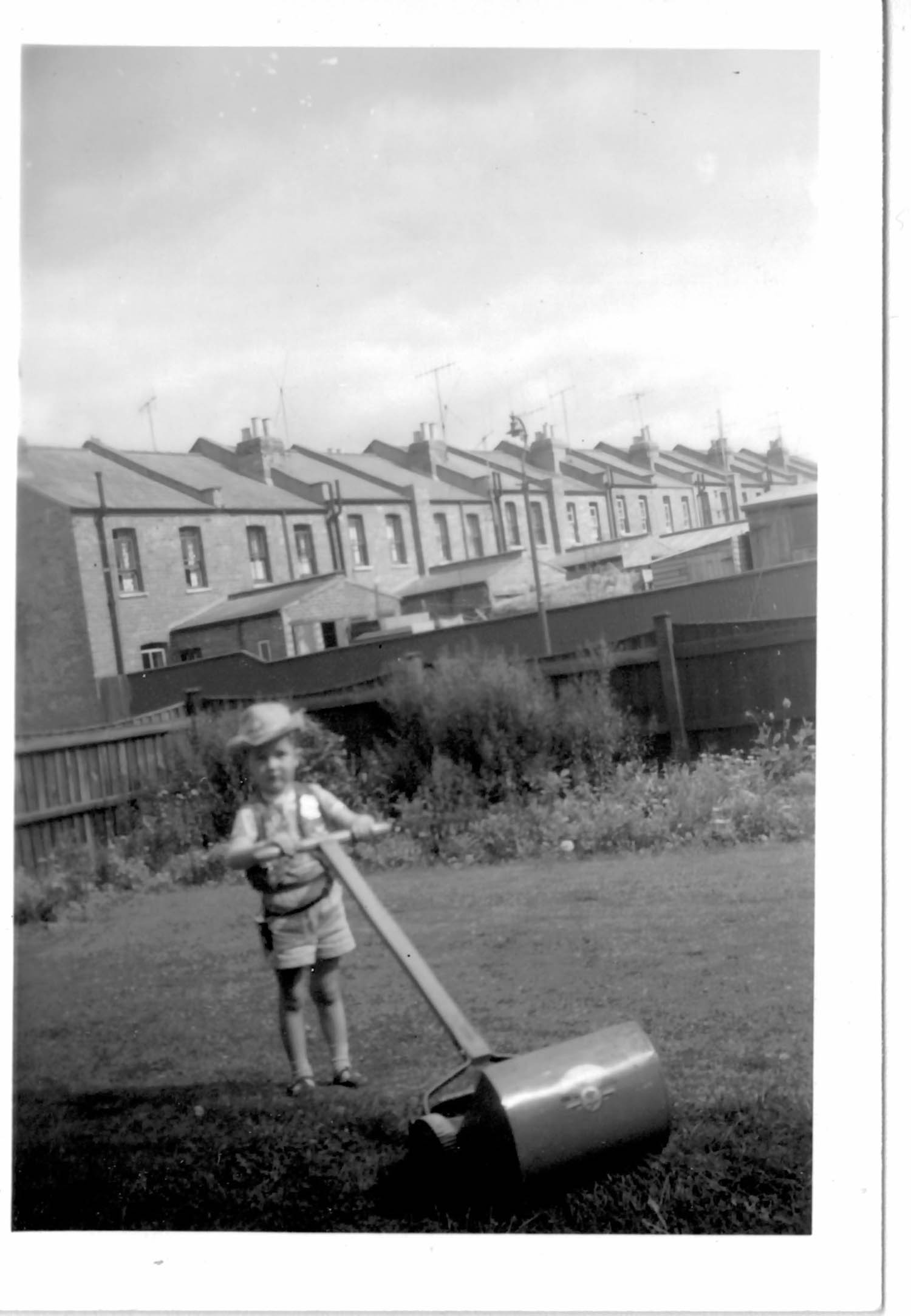

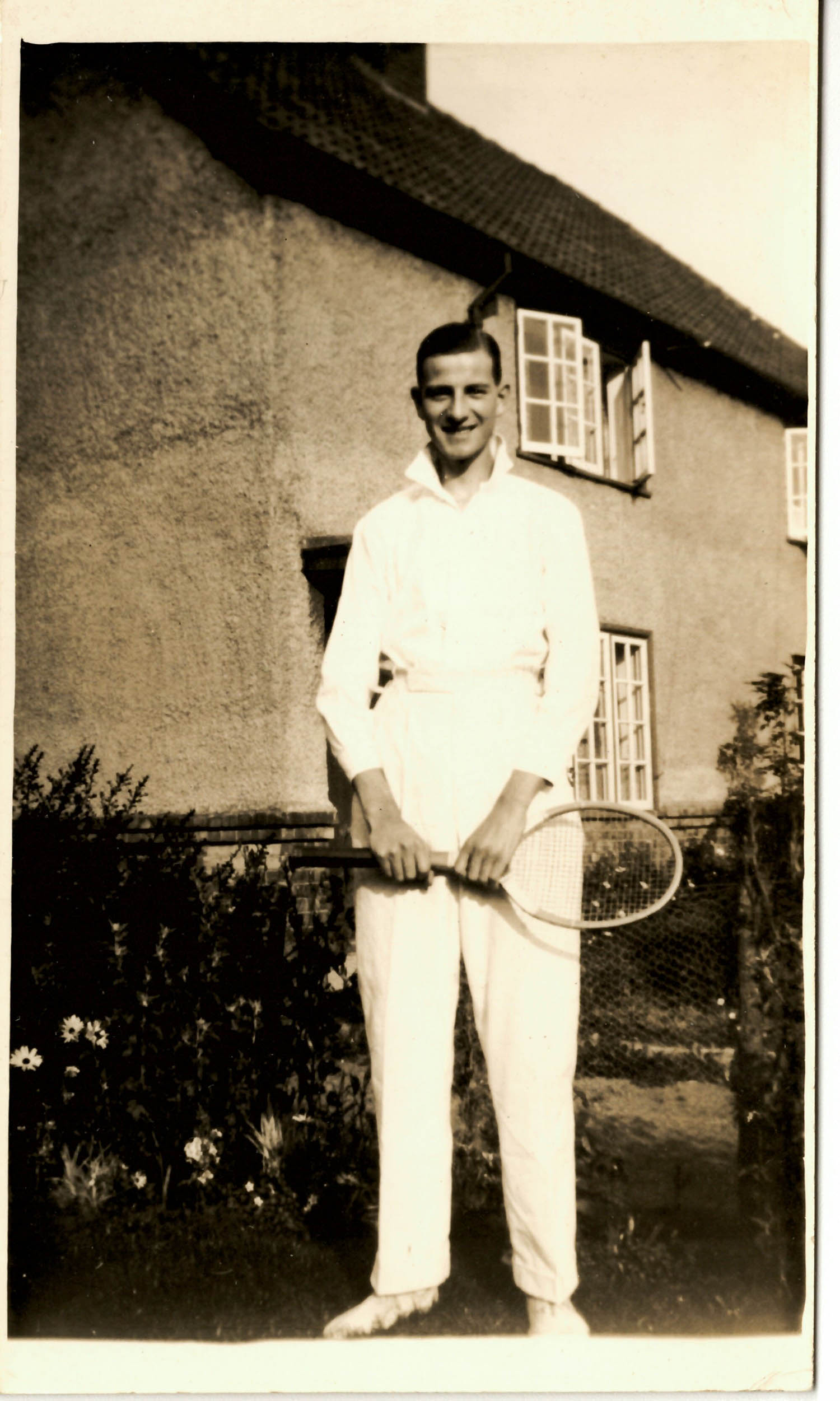

Tennis

I started playing tennis in the garden at home after watching Wimbledon during the end of my first year at grammar school. This is not quite as splendid as it sounds. Repeatedly rollered, doggedly refusing to be flattened, the lawn was just about big enough for badminton but not wide or long enough for a tennis court (let alone for the extra space needed beyond base- and tramlines). At first we didn’t bother with a net as we would just be hitting. My dad had been a good player in his youth – there’s a photograph of him in his late teens, in tennis whites, lankily holding his racket outside the family home on Leckhampton Lane – and he stroked the ball towards me. I swiped it back but it flew over the hedge – past the slips, in cricketing terms – into next door’s garden. We stopped playing and clambered over the fence to look for the missing ball. After 10 minutes we found it in the hedge separating next door’s garden from their neighbour on the far side. Frustrating though it was, this search-and-rescue mission defined my attitude to tennis equipment in two important ways.

First, I understood that although it is called a tennis racket, the function of this implement is not confined to hitting a tennis ball but also includes the capacity to prod and poke into hedges, thereby transforming the person wielding it from a tennis player to a fringe participant in a hunt, a beater flushing out game (more exactly, the means by which the game might continue) from the vegetation in which the ball has secreted itself.

Second, that a tennis ball was not a disposable thing but a rare and valuable item, the loss of which was to be neither countenanced nor endured. It was a point of principle that we would not start playing again until we had found the missing ball and, since the ball went missing every three or four minutes, an hour’s tennis only included about a quarter of actual tennis, the remaining three-quarters being spent poking and prodding the bushes in our neighbour’s garden.

There was an element of the good shepherd about my father’s unwavering determination not to let one of our balls go missing but there was also a stronger hint of miserliness. Couldn’t we just let it go and use – and then buy – another? The idea was a literal definition of nonsensical. It made no sense.

For our game the following day, my dad tied a length of frayed string to two rusty poles driven into the ground so that we had a net of sorts, or at least a line – the horizontal equivalent of a plumb line, reminiscent of the string at the strawberry-picking fields – over which we tried to hit the ball, though mainly I continued spraying it over the hedge-net, into next door’s garden.

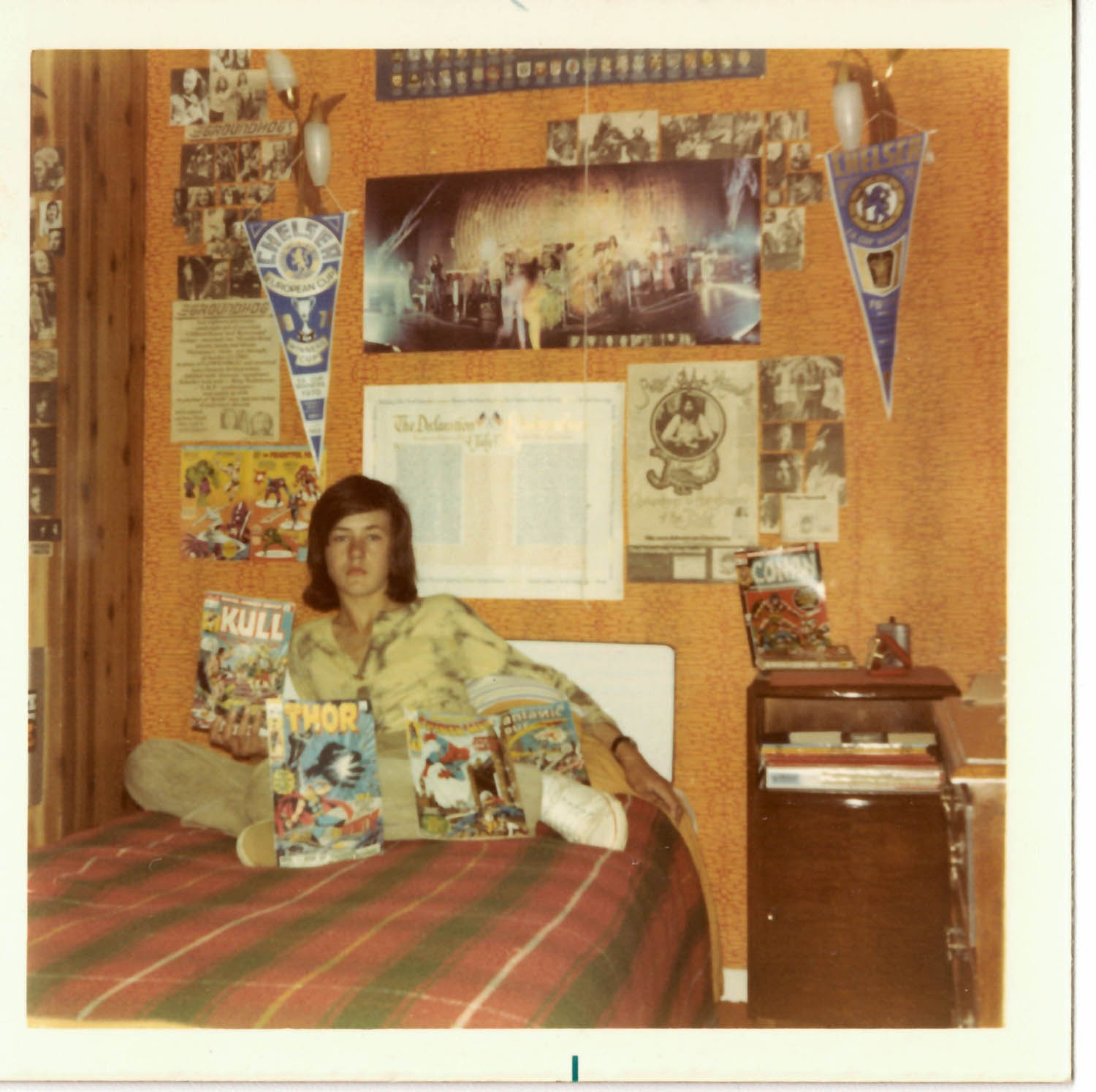

Counterculture

A picture of me [above] in my bedroom shows the tie-dyed phase when Chelsea paraphernalia and prog rock held each other in brief equilibrium. Internal evidence – album covers, the advert cut from the NME for Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night, the solo album Peter Hammill put out after the breakup of Van der Graaf Generator – suggest this was taken when I was 15, probably just shy of my 16th birthday. Chelsea pennants and rosettes are draped from the light fittings but the centrepiece of exhibit A is a long horizontal poster of Hawkwind on stage. Although I had the merch, I didn’t realise that Hawkwind were a deeply druggy group. The word acid kept coming up in interviews with them but I didn’t know what this was and it didn’t worry me that I didn’t. On that same trip to London when I bought In Search of Space, I’d also bought a paper called Frendz that seemed devoted almost entirely to Hawkwind. On the cover was a picture of balding and bearded Del Dettmar (synth), happily reading the Dandy. The agenda of this radical underground publication meant almost nothing to me. I didn’t even know what “underground” meant except, courtesy of the Oz trial, obscenity and sex. A printed letter in Frendz read something like: “Nick Kent must be a pretty far-out screw, huh? He writes like a pig brick.” What did that mean? Did it matter that I didn’t know?

What mattered – the point that needs to be made – is that by 1973 a version of hippy style had percolated down to the third and fourth form of Cheltenham grammar. Our most egregious, and therefore frequently thrown insult, was “plastic hippy”. On a wish list for Christmas at about this time, I asked for a pair of “bell bottom hipsters. Colour: purple.”

Pubs

There were so many pubs, and although we liked some more than others, there were none that we disliked – except the ones where you couldn’t get served. That was all that mattered: getting served, and as long as you could pass for a day over 16, it turned out that most places were more than happy to oblige. The only thing we liked more than the word “pub” was when it was followed by the word “crawl”.

A pub crawl was the ultimate form of social life, though we loved any pub we were in so much that it was difficult to muster up the willpower to crawl to the next one. Another disincentive was that all pubs, the one we were in and the ones we might move on to, suffered from the same glaring deficiency: a shortage of girls. In this respect, life in a pub was no different to life outside it. Always that same unanswerable question: how to meet girls. The problem with pubs was the problem with girls; they didn’t like them (pubs) as much as we did, didn’t go to them nearly as much as we did, and didn’t seem to like us as much we liked them (girls).

And remember, it was the pub or bust back then. There were no alternatives: no cafes, no nightclubs (except in the form of the discos we went to after the pub for the simple reason that the pub had shut). Girls made up half the population of the world – except in Cheltenham, where the figure seemed to have somehow dwindled to about 10%. Where were they? Another problem with pubs, though it wasn’t really a problem, was some of them weren’t very nice. Not that it mattered: they were still pubs. As an example of a pub that I went to a lot, with no redeeming qualities other than proximity to 1 Woodlands Road, I present to you… the Double Barrel.

It was just down the hill from our house, right across the road from the depressing stretch of shops where we’d vandalised the clock at the launderette, a five-minute walk away and therefore significantly closer than the Shurdington Arms (unappealing) and the other boozers at the top end of Bath Road, notably the Exmouth Arms (nice beer garden) and the Five- Alls.

A more characterless boozer than the Double Barrel is hard to conceive. It fulfilled the basic definition of a pub in that it had chairs on which you sat and beer you could swill. Once, when I was four pints into an evening with friends from school, our next-door neighbour Mr Meetens came in for last orders. Wobbling up to him and slurring a few boozy words felt like the most grownup thing I had ever done. I could look forward to a lifetime of this, a lifetime of boozy chat in boozers.

Homework: A Memoir by Geoff Dyer is published by Canongate (£20). Order it at observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Myung Chun/Contour RA by Getty Images