Throughout the inimitable Septology, Jon Fosse’s artist protagonist, Asle, repeatedly returns to his conviction that every picture he’s produced, in a lifetime of painting, has sprung from a single source; a one true innermost picture about which he can never speak. The symbiosis of fixation and creation may be something of a commonplace but, as the novel-by-novel persistence of Fosse’s own preoccupations attest, it is still a potent catalyst for art. This remains true of Vaim, his first novel since receiving the 2023 Nobel prize in literature.

Consequently, it’s little surprise to find ourselves washing up on Vaim, the island home of elderly boatman Jatgeir, the first of the novel’s three vacillating narrators. Again, we are returned to the islets, fjords and small boats of Fosse’s inconcrete west Norway: its liminal nature indicated by the unusual passivity of its bewildered male inhabitants, as well as Fosse’s customary use of the old Norse “Bjørgvin” in place of modern-day Bergen. The novel opens with Jatgeir being cheated by a female shopkeeper out of the exorbitant sum of 250 kroner for a needle and spool of thread. Outraged as he is, Jatgeir convinces himself that, given the infamous rapaciousness of Bjørgvin-ites, especially towards country bumpkins – as he’s mortifyingly sure he appears to them – little better could be expected. To prove his theory, he heads to a country shop and asks another female shopkeeper for another needle and thread. When she too demands 250 kroner, Jatgeir is, once again, so paralysed by the shamelessness of her swindle he can only hand over the cash and reel back to his boat for a lie-down.

Cringing and rationalising his spinelessness – “the only thing I could do was pay and look happy about it” – he doesn’t realise worse is afoot. Before long, the immovable object of his inertia will meet the unstoppable force of Eline, and then his troubles will really begin. The secret love of his lost youth – and namesake of his beloved boat – Eline harbours no comparable reservations about acting in her own interest and has already staked Jatgeir out as the perfect vehicle for her latest drastic life change. Before he knows it, she has invited herself aboard, suitcase in hand, and they’re hightailing it back to Vaim before her fisherman husband, Frank, returns in his new boat – which will soon also be dubbed “Eline”.

The second section deals with Elias, Jatgeir’s similarly indecisive neighbour, who cannot bring himself to answer the repeated knocks on his door. Instead he ponders why, since the arrival of Eline, his friendship with Jatgeir has dwindled. Like Jatgeir, Elias is tormented with insecurities about how he is perceived, namely as a “prayerhouse” and church person. This wounds him, despite the fact he is a prayerhouse and church person. Although he doesn’t embrace it and isn’t a believer. Except when he is and does: “Not that I’m a believer, but I go to the prayerhouse and the church anyway just to be with other people, and I’m kind of a believer too, in my way, and I look forward to going to church on Sundays…”

When Elias finally opens the door, no one’s there. Shortly afterwards, a distracted Jatgeir drops by but leaves before discussing what he’d come to say. When Elias takes a walk to the pier, he discovers Jatgeir’s body had been pulled from the sea earlier that day – a sequence of events in line with Fosse’s recurring interest in populating the space between life and death.

Vaim’s third section features Frank and his appraisal of his convoluted relationship history with Eline. They met when she approached him in a bar, danced with him – although he was quite embarrassed by that – then told him to get in his boat and take her back to his house where they were going to set up home together. Echoing Jatgeir’s lack of assertion around women, and despite some perfectly reasonable doubts about marrying someone he’d only just met, Frank does as he’s told, even in the face of Eline’s refusal to call him by his actual name, which is not Frank at all but Olaf. That said, Jatgeir’s real name is Geir and, despite Eline calling herself Eline, her given name is Josephine, although everyone else calls her Franke-Frenke, which Frank-Olaf thinks is “pretty rude” because no one likes to be misidentified, except, perhaps, when they don’t mind: “It took me a long time to get used to also being called Frank, as well as Olaf, to tell the truth I never really got used to it… but actually it was fine to be called Frank too, I got used to it.”

Fosse’s intrepid, seductive, highly accomplished writing perfectly fits the intricate human truths he seeks to convey

Fosse’s intrepid, seductive, highly accomplished writing perfectly fits the intricate human truths he seeks to convey

Insecure and anxious, the male characters return time and again to reaffirm the veracity of their impressions while simultaneously questioning their understanding of events, casting doubt on their positions, reassessing all previous declarations, and gradually silting up the text with repetitive assertions and instantaneous reversions. As with Fosse’s earlier novels, this volte-face of logic features heavily throughout. In Vaim, however, it’s deployed to more comic effect than previously, adding an unexpected warmth. Without compromising the sting of existential confusion his characters suffer, Fosse has given the novel a tint of black humour that has more in common with Gogol than Hamsun or Ibsen.

The “double”, another Fosse fascination, resurfaces as well. Jatgeir/Frank – both older, single boatmen living in untidied houses bequeathed them by long dead parents – are the latest additions to Fosse’s alternative Norwegian universe, in which men may frequently live on islands but rarely turn out to be ones themselves. While, in Vaim, Eline remains individuated – apart from the more fondly regarded boats named after her – a long line of Fosse’s reins-taking women precede her too. Sometimes they exert a positive, transformational influence on the male characters. Sometimes, as here, they merely highlight his protagonists’ submission to the unknowableness of fate. But always they elicit the author’s backhanded admiration of their annoying willingness to assume responsibility.

It’s this enmeshment of characters, narratives, novels and landscapes that feeds the aggregate pleasures of reading Fosse. In its service here again – and wonderfully wrought by translator Damion Searls – Fosse’s prose continues to cunningly prioritise a plain, unliterary vocabulary. But this unfolds into a mobile, reactive, single-sentence structure that recedes and builds, in concert with his character’s many reiterations, until its rhythmic, poetical lure becomes irresistible to any reader with half an ear to hear.

“And I think that now I don’t understand anything, now I can’t be awake, because this must be a dream, and it’s not like it matters much, a dream is a dream and reality is reality, but in a way reality has probably always been, yes, no, no not like a dream, but reality has had something dreamlike about it probably my whole life, reality is in the dream the way the boat is in the water, I think, or maybe the other way around.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Fosse’s is an intrepid, seductive, highly accomplished writing that perfectly fits to the intricate human truths he seeks to convey. If this book initially appears somewhat slight, it’s worth noting – in familiar Fossian form – further Vaim novels will soon be layering up its terrain. Until then, as Frank-Olaf observes, “all was strange”. For so it is. And so it isn’t too.

Vaim by Jon Fosse, translated by Damion Searls, is published by Fitzcarraldo Editions (£12.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £11.69. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

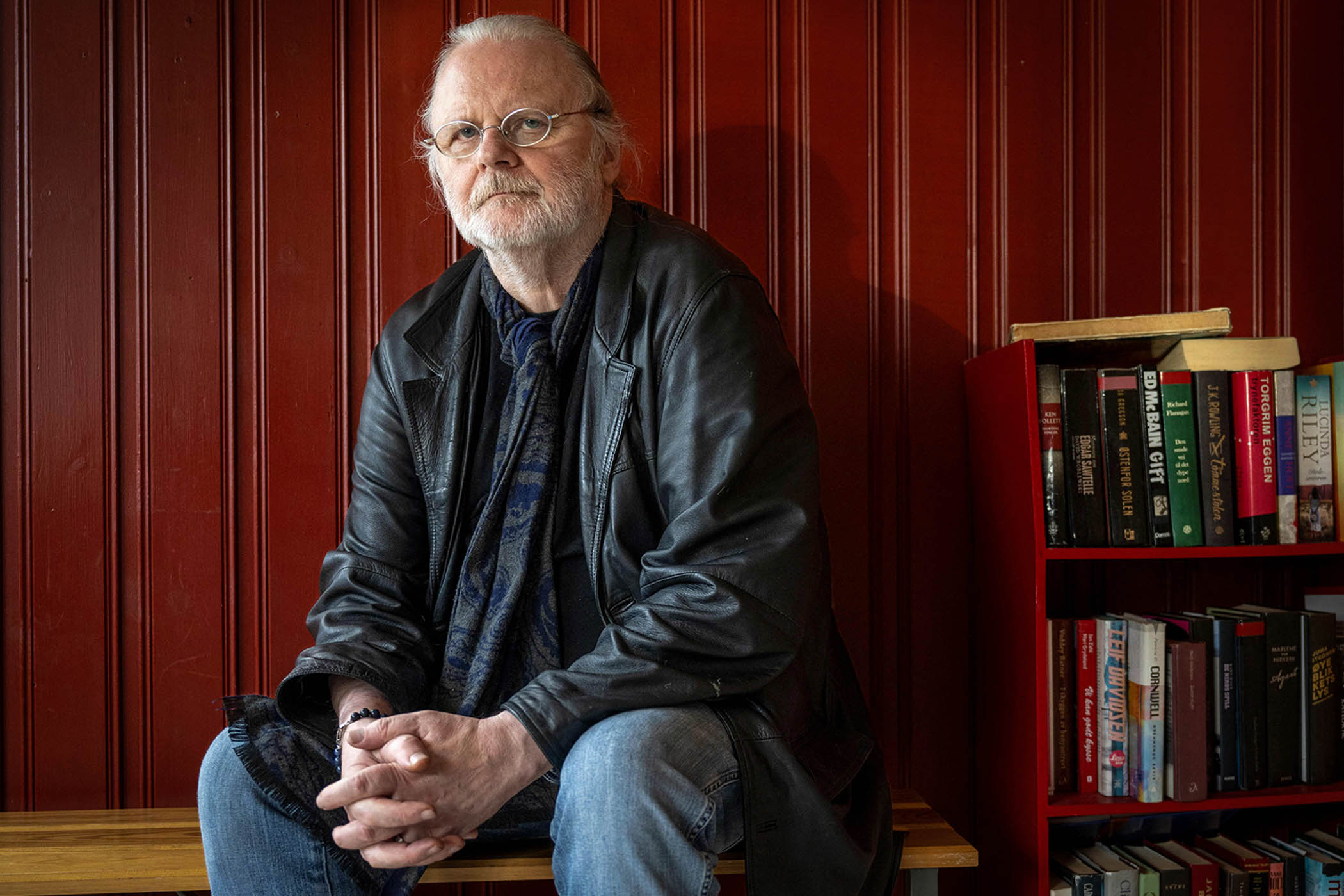

Portrait by Bergensavisen/AFP/Getty Images