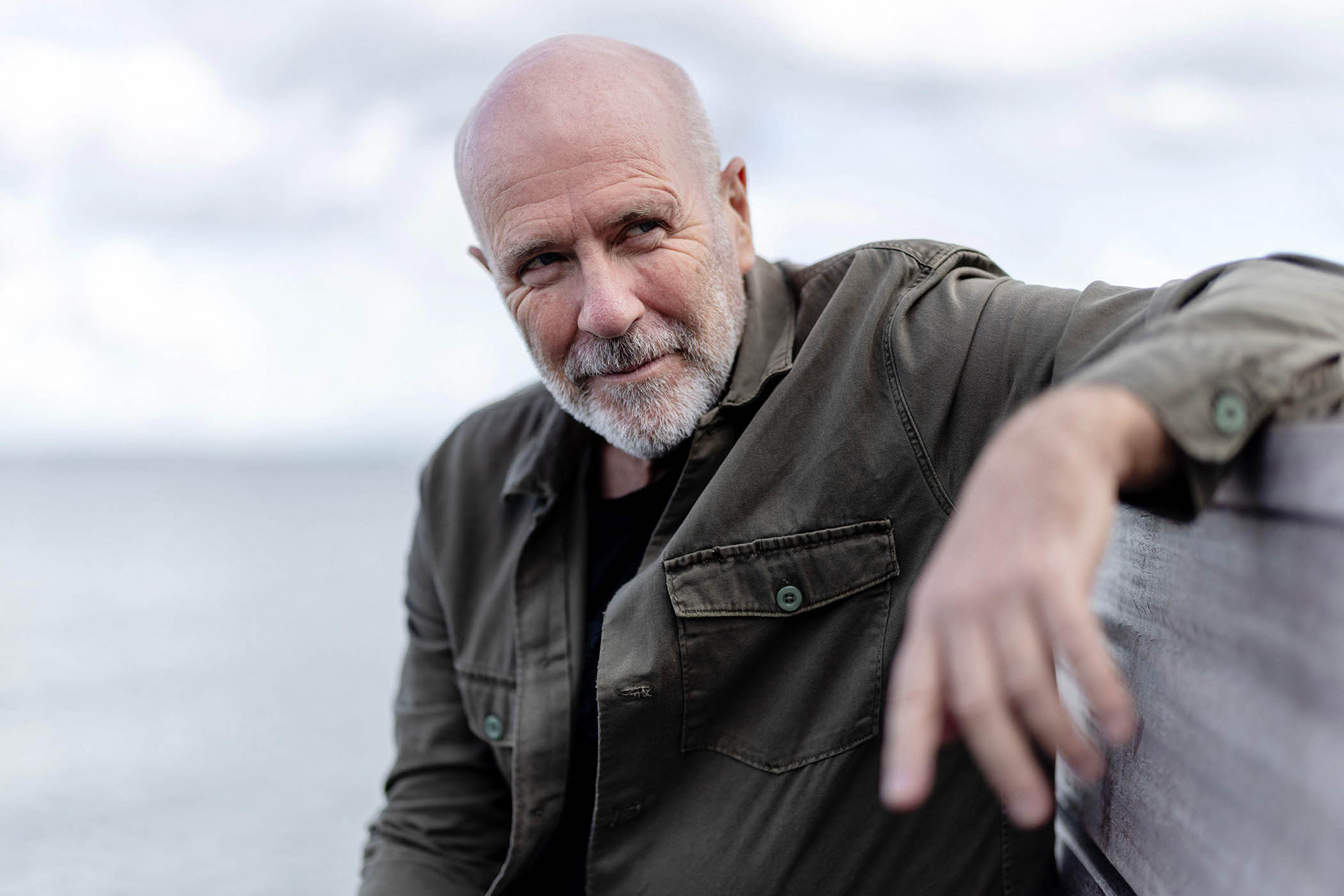

Richard Flanagan was born in Tasmania in 1961. He won the Booker prize for The Narrow Road to the Deep North in 2014, and the Baillie Gifford prize for nonfiction for Question 7 in 2024. This is an edited version of an interview that took place at the Jaipur literature festival last week.

Question 7 is both an intimate family memoir and a book unafraid of asking the big questions. What was the impetus for writing it?

When the book first came out, I wasn’t entirely honest about its origins. Writers rarely are. But what had happened was I’d had a diagnosis of early onset dementia, which was troubling, as [my brain] was about the only functioning organ I thought I had left. I was given 12 months to settle my affairs, after which, you know, things were going to get bad very quickly. I decided I wanted to write a book about what it is to live and what it is to love. So I spent these 11 months when I was meant to be getting my affairs in order writing this book. I sent it off to my publisher of 30 years and I waited with some trepidation. After about a day, she rang and my very first question, which I stammered out, was, “Does this show signs of cognitive collapse?” And she just started to laugh. A couple of weeks later, I saw the neurologist again, and there had been a mistake in the radiologists original readings of the MRIs. There was no early onset dementia.

In retrospect – and given the happy outcome – does the original diagnosis now feel like something of a gift to you as a writer: the urgency about having to make this kind of statement of account?

Well, yeah. I mean, writers are dreadful procrastinators. I could have spent that year sharpening pencils. I recall that Anthony Burgess was given a terminal cancer diagnosis in 1964 and in the following year he wrote three books: two of which are lost to anyone’s memory, but one being A Clockwork Orange. And, of course, he then didn’t die.

It is no surprise then that this is a book of memory. In writing it, were you almost testing what you could recall against what you knew to be true?

I think we have this idea in the west that memory is an act of testimony. But memory is also an act of creation. It’s very odd as a novelist to revisit events which you believe are foundational to you, and find that perhaps many things never happened at all – that you’ve just invented certain ideas about yourself, and you’ve lived in those stories. Writing this book, I came to think about time a lot, and the way we conceive of time. European ideas of time never felt very satisfactory to me. I grew up in a culture [in Tasmania] where time was circular and people told stories that never really began and never really ended, but digressed endlessly. The book is written in a way where the past is always alive.

Part of that past is concerned with your father’s history as a prisoner of war in Japan – and the fact that his life was almost certainly saved by the dropping of nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, without which you would not have been born. You trace that history back to the moment when the idea of a nuclear bomb first appeared in the human imagination – which you isolate, brilliantly, in an amorous encounter in 1912 between the writer HG Wells and the free-spirited Rebecca West.

Yes, immediately after that Wells felt he had to escape to the house of another lover in Switzerland – he had a complicated love life – where he continued reading deeply about advances in understanding radium, and went on to write a book called The World Set Free, in which he first imagined the atomic bomb. That book was very influential in the thinking of a young Jewish émigré in London, Leo Szilard, who first understood the physics of [the bomb], and proposed the idea to Roosevelt of what became the Manhattan Project… without which my father would not have survived the war and I would not be sitting here talking about this book.

Question 7 gets its title from a question posed by Chekhov. What was that?

Chekhov famously said that what made Anna Karenina a great book was that “it frames the questions correctly”. Among Chekhov’s earliest writings, when he was an impoverished student trying to support his family, he used to write these comic sketches for newspapers to supplement his income. One of these very early stories is a series of absurdist jokes, and it’s presented in the form of those mental arithmetic problems you’re given in school. Question seven of the 12 questions asked by a mathematician goes like this: “On 17th of April, a train leaves station A at 3am and arrives at station B at 11pm. Just as the train is about to depart, an order comes that it must arrive at station B at 7pm. Who loves longer, a man or a woman?” [Laughs] In that question, I think you have the genius of Chekhov. His stories always begin in a seemingly real world, a dinner party, but finally he goes to this other place, this subterranean place where great books go. That’s where the real world is, the world of those questions that actually haunt us in the middle of the night: Who do we love? How should we live?

Very few of those questions have rational answers.

There’s that great line of Dostoevsky’s where he says, in Notes from Underground, that reason is a very fine thing but the rivers run with blood and wanting is the sum of all human life. In part, Question 7 deals with how inadequate rationality is when set against the strange wantings and irrationality of us as human beings.

You write about how you had a hearing problem as a child – corrected when you were six – which meant you found it hard to form words. There’s a sense that the writer was created in that time: you couldn’t communicate, but you were desperate to communicate. Is that how you look back on it?

I’m not really much interested in myself. So even with this book, which pretends to be about me, it’s about other people. I guess what I did learn from this period of deafness is that once you have these disabilities, you become written upon. You’re told who you are, you’re defined. I think books did seem to me a way out of that; or the written word did, because I didn’t have the spoken word. But the other thing that helped was two generations of free state education. My grandparents were illiterate. But my father, who was the only one of his family to get something beyond a two or three year education, had this profound sense of the magical power of the written word. He understood that in English, the 26 abstract symbols of our script are magical in their power to conjure up worlds, that they are liberating and transcendent. He said to me: “The written word was the first beautiful thing I ever saw.” He could recite long passages of poetry. I think all those things were very powerful in shaping me. My parents didn’t respect success or money much. But they did think that someone who could write, that was a sacred thing.

They must have been thrilled that you became a writer.

They were terrified at the beginning because it wasn’t clear how you’d make money. After I wrote my first novel, my mother said to me: “Well, you’ve done that, now you should find a real job.” I remember a TV crew came to interview me once and my father knew it was a well-known show. He said: “Why are they doing that? They only do famous people.”

There is a great moment in the book where you go to tell your father that you’ve won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford, and he is out in the garden.

Yes, they were so hugely uninterested and unimpressed by these things. I went to tell my mother, who was in the kitchen making bread, and she sort of looked up and she said: “Oh, that’s interesting. Tell your father, he might be interested.” So I went out to my dad and he was in the backyard forking compost, which is what he spent much of his later life doing. So I go up and tell him and he doesn’t turn around. He just keeps walking through the peat and the worms. He says: “If you should meet with triumph or disaster, treat these two imposters just the same.” That was the end of it, and I just laughed.

What did you learn above all from that extreme year writing this book?

I think perhaps the problems of our age are not just the awful things happening around us, but that we too easily take our compass from power. If you look at your phones and your screens all the time, all you see there is power’s propaganda. And if you take your compass from that, there is only despair. But that’s not the real world. The real world is the people around you: your family, your friends. If you look to them, you see flawed people like yourself, but you see kindness and goodness every day. And that is a source of enormous hope.

Question 7 is published by Vintage (£10.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £9.89. Delivery charges may apply

Portrait by Anders Hansson/Alamy

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy