Related articles:

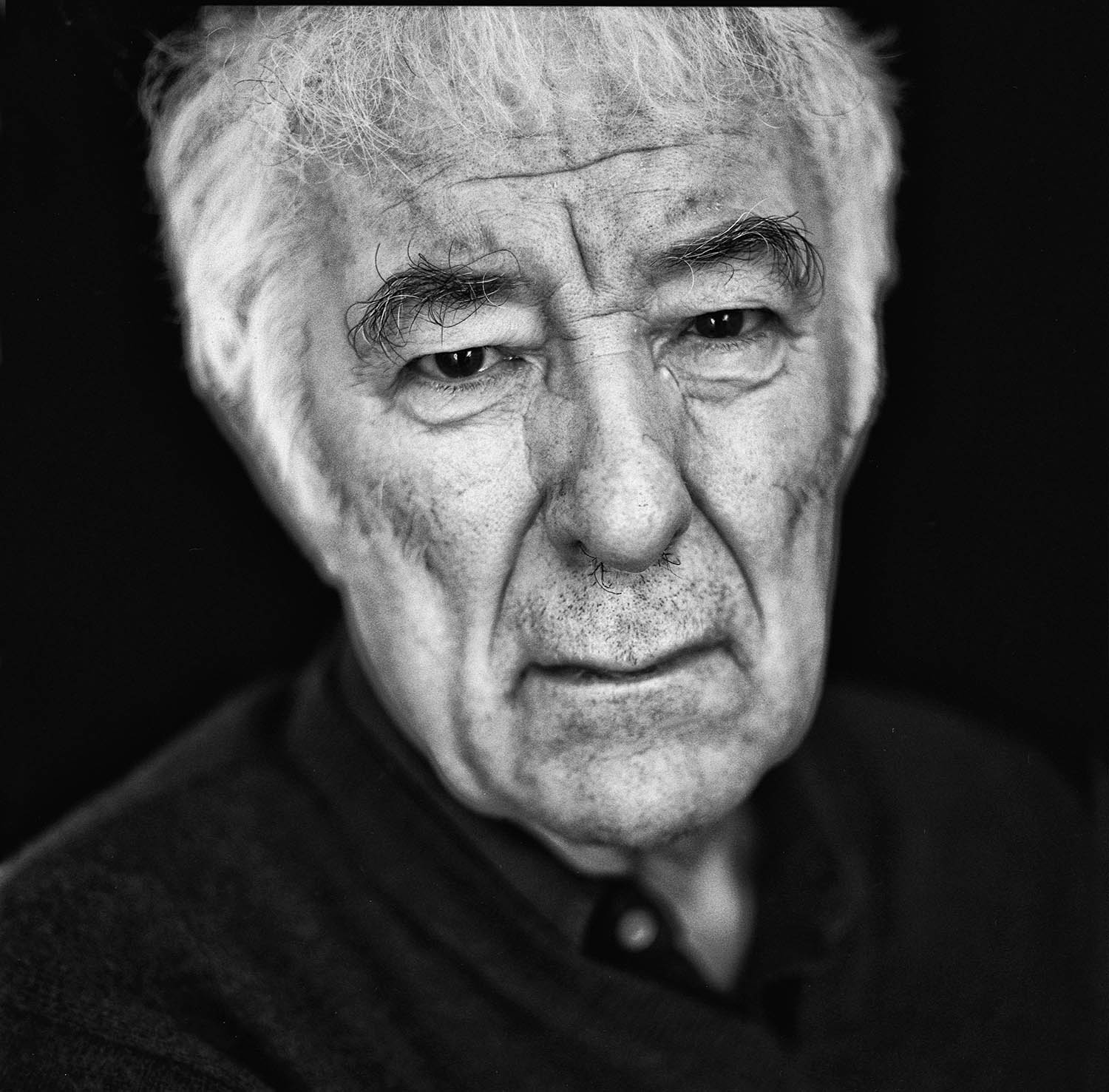

Portrait by Antonio Olmos

A place I happen to know very well is the Flaggy Shore, a thin spit of land that sticks out into the south side of Galway Bay. In the autumn of 1992, Seamus Heaney drove up the narrow tarmacked pathway with his wife Marie, the great playwright Brian Friel and his wife Anne. He does not seem to have bothered to get out of the car, or even to stop for a few minutes to take in the scene. Because the path is usually blocked by walkers, it’s a slow drive – but still it couldn’t have taken him much more than 10 minutes. He had, as he later recalled, a “quick sidelong glimpse of something flying past”.

Yet from that sidelong glance came one of Heaney’s most loved poems, Postscript. It came, indeed, very quickly – and was published in the Irish Times almost as soon as it was written. In the original version, the poet tells himself as he is driving along that it is “Useless to park and think you’ll capture it / More thoroughly or indelibly”.

And yet the place is indelibly captured in Postscript. Every time I walk the Flaggy Shore I am awestruck yet again by how precisely Heaney’s sidelong glance takes everything in, like a cinematographer sweeping his camera slowly across the scene: the wind and the light “working off each other”, the sea on one edge wild with “foam and glitter”, and on the landward side the strange little “slate-grey lake” that is always lit by the “earthed lightning of a flock of swans”. There’s a slyly brilliant paradox playing itself out here – the exact re-creation in memory of what, we are being told, memory could never apprehend.

There’s so much else going on in the poem’s 16 lines. As you come in to the Flaggy Shore, you pass a solid if unspectacular house called Mount Vernon, which used to be the summer home of Augusta Gregory, the great friend and collaborator of William Butler Yeats.

Yeats spent a lot of time here and, although he is not explicitly mentioned in Postscript, those swans in the little lake, “Their feathers roughed and ruffling”, are a flashback to Yeats’s Wild Swans at Coole that “drift on the still water, / Mysterious, beautiful”. Heaney is subtly placing himself, not just in this landscape, but in the flow of a living tradition of which he is part. This Postscript is also a PS I Love You to the great mage of Irish poetry.

The glorious gathering-in of his achievement that is The Poems of Seamus Heaney, edited with meticulous care and luminous clarity by Rosie Lavan and Bernard O’Donoghue (with Matthew Hollis), allows us for the first time to see his dozen formal collections as only the most visible peaks in a constantly rolling range of creativity. Among the 700-odd poems are around 200 that were published in journals and newspapers yet never included in Heaney’s collections, plus 25 unpublished pieces chosen by his family from the working papers he left behind at the time of his death in 2013.

This arrangement allows us to see Heaney’s oeuvre as a living, organic entity. Thus I was struck by how Postscript is also a PS to an earlier Heaney poem, The Peninsula, first published in 1966, the year of his thrilling debut collection Death of a Naturalist. This poem is also 16 lines and again finds Heaney (the poet laureate of the internal combustion engine) driving around a strip of land that juts into the ocean.

Related articles:

The Peninsula is written as a note to self – what to do “when you have nothing to say”. The trick, the young Heaney commands himself, is to get in the car and glide round a place that circles back on itself, “The land without marks so you will not arrive / But pass through”. Nearly 30 years later, middle-aged and globally celebrated (the Nobel prize he would win in 1995 already on the horizon), he is repeating the instruction, except this time with a higher voltage of ecstasy.

Postscript is written in defiance of the whole idea of having “arrived” in any sense of the word. It came to him while he was working on his lectures as professor of poetry at Oxford, high panjandrum of all versifiers. But it enters a hypnotic state in which everything material evaporates. Having given us his extraordinarily exact evocation of a real landscape, he lets it dissolve into pure possibility:

You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

Thus, in this one short poem, we have so many of the layers that make the experience of reading Heaney so rich. There is that common, otherwise banal, human experience to which almost any reader can connect – he is not tripping through hosts of golden daffodils but day-tripping with friends. There is the cinematic eye that brings the inanimate world into astonishingly sharp focus – “things”, as he puts it in The Peninsula, “founded clean on their own shapes”. There is the way he keeps alive the whole tradition of Irish and English poetry (Shakespeare, Herbert, Wordsworth, Hopkins and Hughes are as important to him as Yeats and Patrick Kavanagh) by remaining constantly in lively dialogue with his ancestors.

There is that sense, so wonderfully encapsulated in the echoes of The Peninsula in Postscript, of an artistic sensibility that is always true to itself, always engaged in what emerges here so marvellously as a unified life’s work, and yet always ringing the changes, having second thoughts, adding posts to all scripts.

And there is the release into a sense of wonder that is no longer religious. Heaney is marked by both the Catholic faith in which he grew up and by his move away from it. But one of the reasons he matters so much to so many people in our disenchanted world is that, as in that rapture on the Flaggy Shore, he keeps open our back channels to transcendence. For Heaney, as for Yeats, there are moments when “We are blest by everything, / Everything we look upon is blest”.

What is not in Postscript, though, is the other thing that makes Heaney matter: the dark. The poem is unusual in that it came so quickly and in a form not very distant from the final shape he gave it in his 1996 collection The Spirit Level. It has the miraculous feeling of something given purely and freely. Most of Heaney’s poems, as the scrupulous marking of variations in this volume attest, are not like that.

They are hard won from hard times. The freedom of having “nothing to say” in 1966 becomes the bitterly ironic Whatever You Say, Say Nothing five years later, a sardonic take on the violent collapse of his native Northern Ireland, first published in The Listener under the headline “Seamus Heaney gives his views on the Irish thing”.

There are no swans here. The mystic Yeats found himself having to write Meditations in Time of Civil War; Heaney had to confront a literally exploding Belfast: “Men die at hand. In blasted street and home / The gelignite’s a common sound effect.” The heart that would be “blown open” on the Flaggy Shore in 1992 is also the one that, in 1971, has to absorb the shock waves of “the bangs / That shake all hearts and windows day and night”. The lyric poet must say something in a world turned decidedly unlyrical. As he puts it so plaintively: “Yet I live here, I live here too.”

He didn’t live there much longer. Born in rural County Derry in 1939, Heaney had settled in Belfast as a student at Queen’s University, where he later became a lecturer. He was there for the optimism of the first civil rights marches, when it seemed that the sectarian Unionist regime could be forced into peaceful change – and for the slow slide into chaos and violence after 1968. In 1972, he moved from Belfast across the border to the safety of County Wicklow and became (as he wrote the following year in Exposure) “a wood-kerne/ Escaped from the massacre”. But his poetry, as he put it, would shift “from being simply a matter of achieving the satisfactory verbal icon to being a search for images and symbols adequate to our predicament”.

Heaney’s dozen collections are only the most visible peaks in a rolling range of creativity

Heaney’s dozen collections are only the most visible peaks in a rolling range of creativity

The great 1975 collection North opens with Sunlight, and Heaney at his most painterly: “The helmeted pump in the yard / heated its iron, / water honeyed / in the slung bucket / and the sun stood / like a griddle cooling / against the wall.” And then it darkens very deliberately into Funeral Rites: “Now as news comes in / of each neighbourly murder / we pine for ceremony, / customary rhythms.”

This shift is never total – one of the most remarkable aspects of Heaney’s music is that it so typically sounds out in stereo, with delight and dread, love and horror flowing side by side and sometimes, amazingly, melding into a spine-tingling harmony.Think of perhaps his most ostentatiously virtuoso performance, Two Lorries, written in 1993. It is a sestina, a form seemingly designed to drive poets mad with its requirement for the placing of six recurrent words in a complex pattern. Heaney’s sole attempt at it is technically breathtaking, a reminder, if one were needed, of how hard he laboured to perfect his craft.

But the poem is even more startling in its choreography of two Heaneys. There is the private Heaney recalling warm family memories: of a coalman flirting with his mother and offering to take her to the pictures in Magherafelt; of his mother meeting the young Heaney at the bus station in that town as he returns from boarding school in Derry. Then there is the public Heaney who must respond to the IRA’s brutal bombing of the same bus station in May 1993. A very good poet would juxtapose these two kinds of experience. Only a great one could fuse them so uncannily, as the coalman returns as the Greek mythological figure Charon to ferry the dead into the afterlife, the film he promised now a coat of dust from the debris:

So tally bags and sweet-talk darkness, coalman.

Listen to the rain spit in new ashes

As you heft a load of dust that was Magherafelt,

Then reappear from your lorry as my mother’s

Dreamboat coalman filmed in silk-white ashes.

Sweet-talking darkness was one of the things Heaney constantly accused himself of. “Forgive,” he asks the ghost of William Strathearn, a childhood friend murdered in 1977 by two RUC officers, “my timid circumspect involvement.” (Station Island). But that conjunction needs to be uncoupled. Heaney was indeed circumspect. A significant aspect of this collection is that it puts into general circulation directly political protest poems such as Craig’s Dragoons, aimed at the police who attacked civil rights demonstrators in Derry in 1968 (and originally performed on radio soon after), and The Road to Derry, which responded to the massacre of marchers by the Parachute Regiment in the city in 1972 but did not see the light of day until it appeared in the Derry Journal in 1997. It is telling that Heaney chose not to include either in any of his collections. He resisted gut instincts that could not be transmuted into art, steering clear, like Odysseus, of both the whirlpool of propaganda and the monster of indifference.

So, circumspect? Yes. But timid? No. Heaney maintained a brave vigil through the dark nights, waiting imaginatively with the dead. He is the greatest of elegists and reshaped a form previously used to sing the praises of the great and the famous so that it gathers into indelible memory victims as ordinary as the majority of the innocent dead always are. In The Strand at Lough Beg, he kneels in front of his murdered relative Colum McCartney to “gather up cold handfuls of the dew / To wash you, cousin”. This is no whitewashing of horror. It is the cleansing of humanity from the stain of obliteration and amnesia.

In Heaney’s penultimate collection, District and Circle (2006), there’s a lovely translation of an 18th-century Gaelic work by Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin. The poem is posed as a set of instructions to a blacksmith to make him a good spade. But it is, of course, really the command of poetry itself:

No trace of the hammer to show on the sheen of the blade,

The thing to have purchase and spring and be fit for the strain

The hammer is the tough labour of artistic excellence but it is also what Hamlet calls the “form and pressure” of time. That pressure pushes down very hard on Heaney’s art and gives it its great purchase on history. But it never dulls the sheen that radiates out with even greater lustre from this superb monument to his artistic grace and bracing humanity. He and his poetry were fit for the strain, and in these darkening times, his words help us to be so too.

Fintan O’Toole is working on the official biography of Seamus Heaney

The Poems of Seamus Heaney is published by Faber & Faber (£40). order a copy from The Observer Shop for £34. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy