When Donald Trump stood up in Davos last month and delivered his speech to the rich and powerful, he was relying on a story he has been telling since his run for the US presidency in 2016. Characteristically meandering and brash in his delivery, he claimed that the US had been the great rescuer of the world after the second world war, and had ever since been taken advantage of by ungrateful allies.

“We give so much, and we get so little in return.” The solution? The acquisition of Greenland to ward against the threat from Russia and China. Only this, he argued, would make America, and the world, great again. It’s a familiar tale: America the insulted, with Trump as its great redeemer.

Contrast this with Mark Carney’s Davos speech. The prime minister of Canada told a very different – but related – story. In a carefully argued address, he declared we are in “a system of intensifying great power rivalry, where the most powerful pursue their interests, using economic integration as coercion”. He explained how the middle powers – the collective – were under threat, and must unite. O Only then will sense and harmony prevail. “The powerful have their power. But we have something, too – the capacity to stop pretending, to name reality, to build our strength at home and to act together.”

In Hollywood, Trump’s speech would be the knackered fifth instalment of an action-adventure franchise – Maga 5.0: Nuking Nuuk. We, the audience, know this script well; we’ve seen it many times before, but it remains a commercial juggernaut. Carney’s, in contrast, is the feelgood breakout hit precisely because it tells a different story – how collective good can overcome the evils of the self-interested few. He received a standing ovation from the room.

After reading John Yorke’s new book, Trip to the Moon, it’s hard not to read every big news development as evidence of the tectonic power of the story. Yorke started his career as a writer on the soap EastEnders, and went on to become a successful commissioner and producer at Channel 4, as head of drama, and at the BBC.

Here, he turns his focus not only to fiction and its structures (what he terms the “domesticated story”), but to the power of stories “in the wild”. Whether his subject is political slogans or religious belief systems, Yorke is a scaffolder dismantling and reassembling the structures of the story, making visible why some narratives work so powerfully (#MakeAmericaGreatAgain) and others flop so terribly (Hillary Clinton’s 2016 election campaign slogan #StrongerTogether).

Where Yorke’s first book, Into the Woods, was focused on film and TV, his analysis in this instance soars precisely because it escapes into the real world. He draws on history: in 1945, despite being the symbol of the resistance to Hitler and Nazism, Winston Churchill was beaten in the general election by a Labour landslide – one of the largest in British electoral history. Yorke attributes this to a message on Labour posters plastered across the country: “And now – win the peace.” A story in a slogan, he writes, that “was so simple, so impossible to disagree with, so clever in the way it called for change while inciting a patriotic emotion, it has rarely been bettered”.

Every political movement needs a narrative, and watching Keir Starmer’s weak response to Trump’s Greenland threats, it’s hard not to conclude that this government’s essential flaw is its failure to tell an effective story. In Starmer’s narrative, we cannot infer the protagonist, the antagonist, the intention and the goal. He is stuck in the wings, while the Tories and Nigel Farage’s Reform UK, which is now leading the polls, tell a tale so common in populist movements (which Yorke compares to the premise of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws). “It’s a ridiculously simple story: we are you, and we have a common enemy, one who is in the direct opposite of every value we hold dear. If you join with me, we will destroy them and our beaches will be safe for swimming once again.”

Related articles:

Yorke’s dismantling of how these stories work on us as citizens feels like a public service, granting literacy at a moment of bewildering global rupture.

At the heart of the book is a question: is the structure of storytelling innate, or is it a formula? It’s a problem that has been wrestled over by philosophers, psychologists and writers for hundreds of years. In the early 20th century, the notion that narrative archetypes exist as proof of an inner collective template gained credence after Carl Jung updated Plato’s archetypes, identifying the characters that recur, he argued, universally in narratives – the hero, the wise old man, the trickster.

In Starmer’s narrative, we cannot infer the protagonist, the antagonist, the intention and the goal

In Starmer’s narrative, we cannot infer the protagonist, the antagonist, the intention and the goal

Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949), later theorised that the “hero’s journey” is the “monomyth” on to which all stories are assembled. US film-maker George Lucas’s praise for Campbell after the release of Star Wars further elevated the idea into Hollywood’s own mythology.

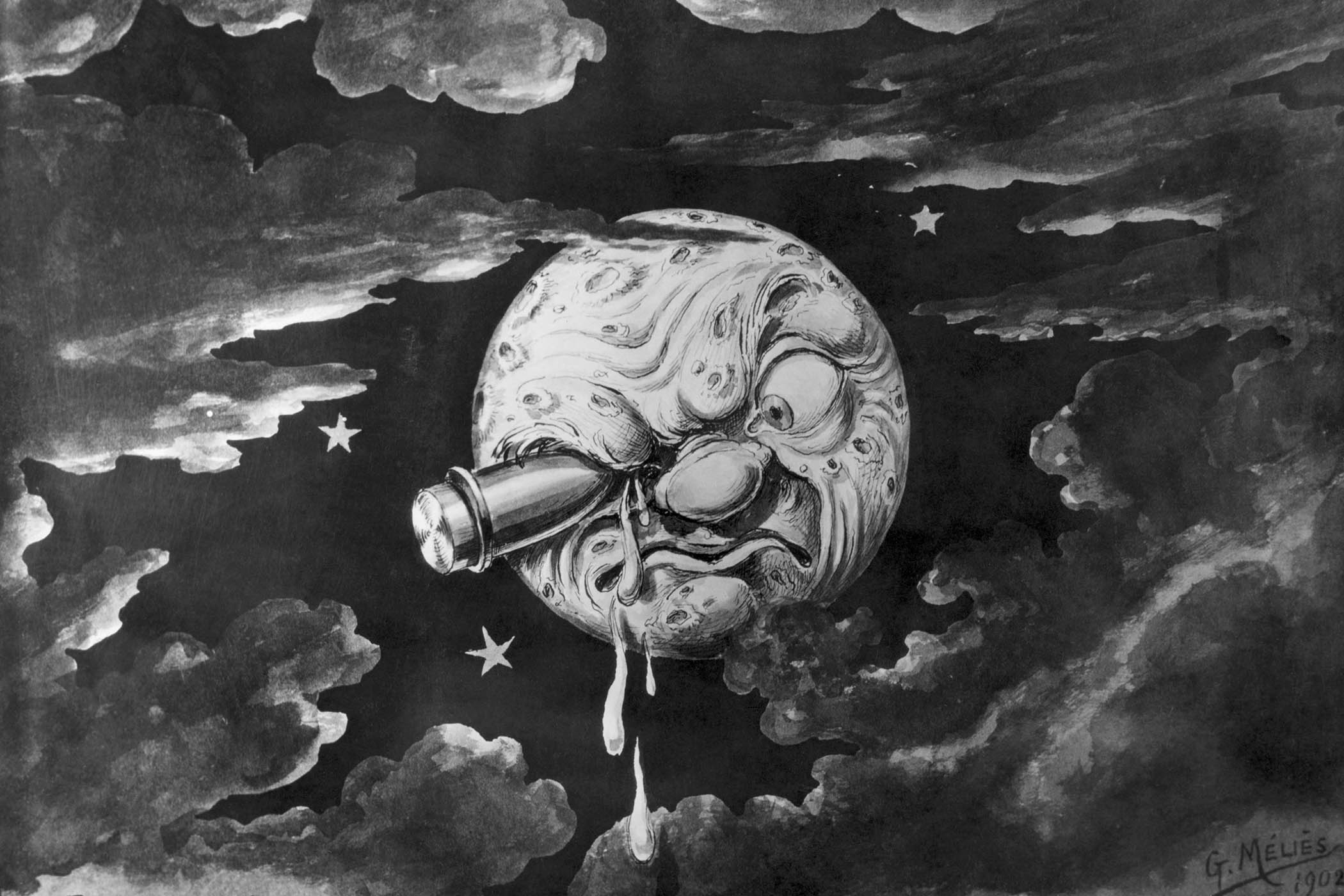

In Trip to the Moon (a reference to Georges Méliès’s 1902 film, among the first narrative fictions on film), Yorke, however, does seem to reject the systematic, structural approach. His book is far from a how-to, despite its many graphs and grids. Instead, he argues that that storytelling is “a product of the human brain as it kneads that complex and random clay, coaxing from it life”.

As AI is increasingly being used across film, TV and even publishing, this question is all the more pertinent. Yes, large language models have ingested the sum of the world’s narratives and can mimic successful storytelling; but is the spirit of the story something only humans can summon? After all, the critical and artistic success of films such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), or Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), lies in the rejection of formula, expectation, traditional timing and construction. Akerman’s 200-minute avant garde epic topped the best film of all time poll by Sight & Sound magazine in 2022. It has always been the case that we learn the rules to break them, and build something new.

Story is both a threat and a tool, and Trip to the Moon reads like a trippy guidebook that doesn’t take itself too seriously, gleaning joy from unlikely but convincing connections, including Coleen Rooney’s Instagram sleuthing (“It’s …………”), Narendra Modi’s political ascent and the opening scene of the TV series Happy Valley. While acknowledging it might seem trite, Yorke connects Hitler’s political message to the allure of the hit BBC show The Repair Shop.

When I interviewed Yorke in 2023, he said “a good story is like a drug”, and there is something undeniably giddy about his journey through history, politics, film and fiction to discover why a good story has the power to transform the world.

Trip to the Moon: Understanding the True Power of Story by John Yorke is published by Particular Books (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £21.25. Delivery charges may apply

Sketch for Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon (1902) courtesy of Bettmann Archive

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy