Blueprints: How Mathematics Shapes Creativity

Marcus du Sautoy

4th Estate, £22, pp304

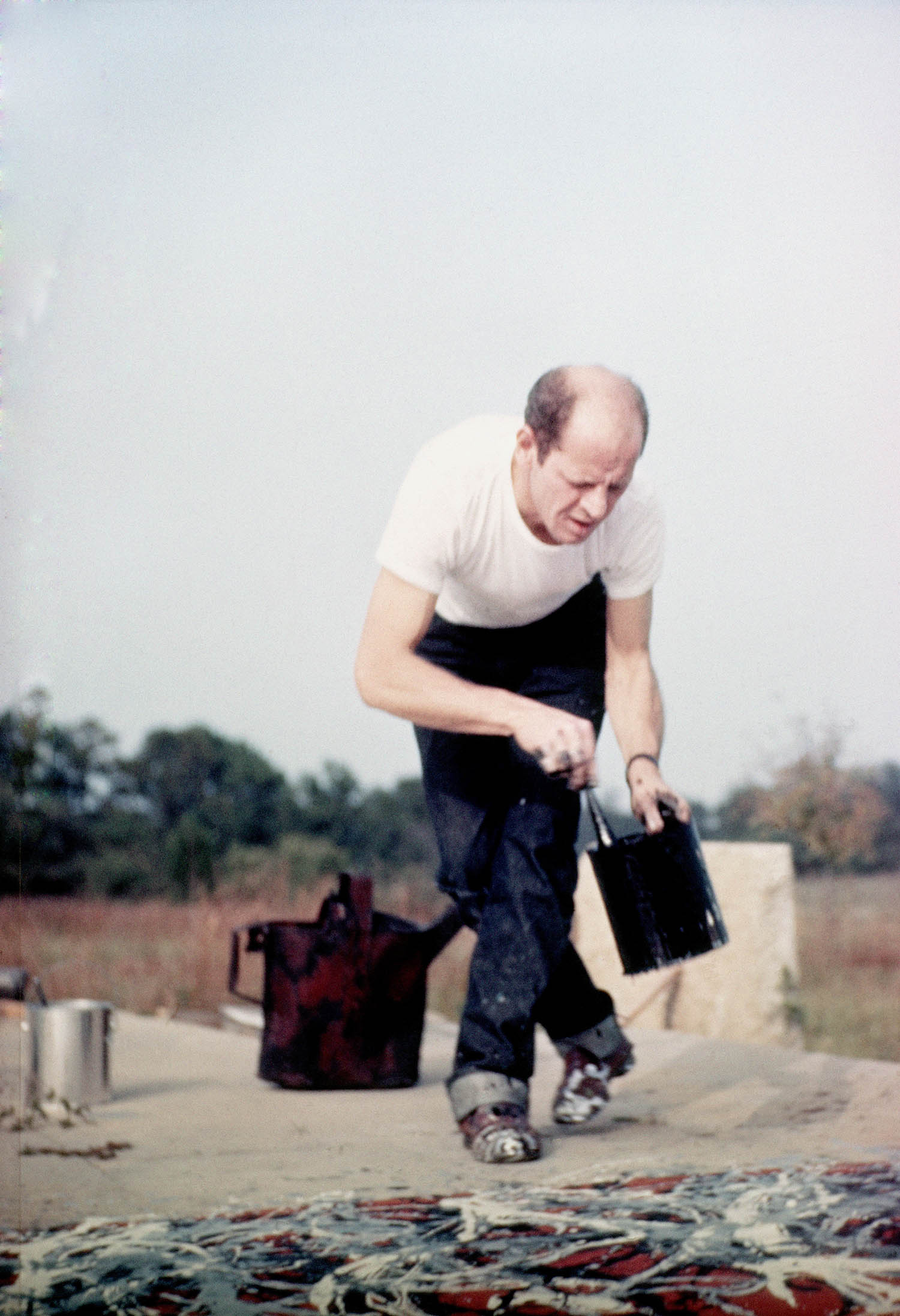

Nothing could be further from the iron-clad laws of mathematics than the US abstract expressionist artist Jackson Pollock sloshing paint over his canvases. Or so you might think. But when a trove of previously unseen paintings by Jack the Dripper came to light after his death, dealers hoping to authenticate them turned not to a curator or art historian but a physicist, Richard Taylor.

In the gouts of paint that went into a Pollock, Taylor discerned a signature of the artist as characteristic as one of Monet’s lily pads or a sunflower by Van Gogh. It was a mathematical structure called a fractal, says Marcus du Sautoy, professor for the public understanding of science at Oxford University.

He calls fractals “the geometry of nature”. No matter whether you look at them from a distance or under a microscope, their shape doesn’t appear to change.

Taylor worked out that fractals such as the ones in Pollock’s work were consistent with the actions of a painter almost losing his balance. That accorded with film of Pollock’s strenuous exertions in the studio, not to mention his well-documented struggles with alcohol. Thanks to maths, Taylor was able to show that the “new” Pollocks were fakes.

It often seems as though art and numbers only go together when money is involved: a box-office take or a new record price set at auction. CP Snow’s influential 1959 essay The Two Cultures argued that educated people were either familiar with the arts and humanities or they understood science and the natural world, but never all of it together.

This may not be true of all societies but it certainly sounds like the Britain that many of us recognise, where clever men and women laugh off their ignorance of maths but would hate to admit that they never open a book.

This may be changing, now that there is more than one generation of digital natives among us. Du Sautoy argues that maths is at the root of a great deal of creativity, whether artistic types are aware of it or not. It supplies what he calls blueprints.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“The mathematics provides the plan or framework. The artist provides the flesh that realises the structure in the medium of their choice: words, paint, music or building materials.” From Anish Kapoor to Zaha Hadid, Du Sautoy fills four pages with just the names of creative people who owe a debt to mathematics. Does this suggest it’s had a big influence on our cultural life? You do the math.

As it happens, you don’t have to, because the author guides us through it himself. The earliest cultures used circles to represent the sun and the moon. Shakespeare’s iambic pentameters follow a pattern of prime numbers. Le Corbusier designed his brutalist masterpiece, the self-contained high-rise commune of L’Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, according to Fibonacci numbers (“each number is obtained by adding together the two previous numbers in the sequence”).

You don’t have to be a book-loving maths dodger to find some of the theory hard going.

Du Sautoy might be a professor of public understanding but I wouldn’t want to go public with how much of the pure maths I understood. Blueprints is a welcome corrective to the complacency of the numerically illiterate but it is hardly news.

Paul Cézanne, the father of modern art, said that painting was a matter of geometry: “Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.” Frida Kahlo’s husband, the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, “loved mathematical construction... and his obsession with geometry was to be of great help when he turned to the problem of making huge, static, formally coherent frescoes”, according to the critic Robert Hughes. Neither of these artists appear in Du Sautoy’s account. Nor does he offer a scientific explanation for the enigma of genius. Although the circle is one of his blueprints, he also recounts how the artist Giotto got himself hired by the Pope by drawing an apparently faultless one freehand. Rembrandt was perhaps alluding to this feat when he added two perfect circles to a 1660s self-portrait.

No one could doubt Du Sautoy’s enthusiasm for his subject: at moments of high excitement, he says, he recites the formula for solving quadratic equations to himself. In this informed and wide-ranging study, he shows that imagination is not the preserve of the artistically inclined – sometimes the so-called nerds are the cool kids with the brilliant ideas (it turns out those laws of mathematics aren’t so iron-clad, after all).

Even if you might struggle with the arithmetic, this is an invigorating read, greater than the sums of its parts.

Order Blueprints at observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Tony Vaccaro/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Science History Lessons/Alamy