“I was born on Christmas Day; my mother was very apologetic and the doctor said: Madame Bourgeois, really you are ruining my festivity.” Thus wrote Louise Bourgeois, portraying her own birth in 1911 as an irksome interruption to the oysters and champagne. “I was a pain in the ass,” she told Modern Painters in 1993. “When I was born, they abandoned me flat.”

But did they? It was 10am in that Paris apartment. Perhaps Madame Bourgeois had laboured all night and cherished her new baby (their letters ring with love, and the anecdote more readily imagines the doctor’s impatience). Surely the oysters had yet to be shucked. But none of this makes a better story than the tale of abandonment Bourgeois gave every journalist from 1982 – when her reputation sprang to life with a revelatory show at MoMA – until her death in 2010 at the age of 98. This genius of modern sculptors was an equally magnificent mythmaker.

Was her very first sculpture really an effigy of her father, modelled in spit and dough, its limbs amputated before his startled eyes? Was she really named after Louis Bourgeois to placate him for the disappointment of a girl child? Did he really have an incestuous love for her? Everyone who knows the art also knows the accompanying narrative of the long-suffering mother, the philandering father, the English governess who becomes his mistress in the 1920s (stout Sadie from Blackheath) and the pretty little girl they all spoiled. These early betrayals will inspire the grief and fury that sustain Bourgeois’s work. “All art,” she would tell pilgrims to her brownstone in New York, “is an exorcism”.

Marie-Laure Bernadac lived in that brownstone to research her book, first published by Flammarion in 2019, now translated for Yale by the writer Lauren Elkin. Venerable curator of three Bourgeois shows, Bernadac was given access to the colossal archive of diaries, letters, loose-leaf observations and psychoanalytic writings “discovered” in the 21st century. Bourgeois flatly denied ever undergoing analysis, yet she attended sessions several times a week for more than 30 years. Bernadac persuasively suggests that this aided the storytelling, and the stories allowed Bourgeois a measure of actual privacy. But she does not go any further. Discretion, prudence, professional tact: all these virtues mar her biography.

It appears a comfortable childhood of gardens, toys and picnics, of days in the family’s tapestry-restoration business or its elegant shop on Boulevard Saint-Germain. Photographs show Louise in Chanel in Cannes. To Bernadac, a group shot with father, brother and governess in Nice resembles a couple with their offspring, though it does not to me. Sadie looks away and M Bourgeois stands askance.

But perhaps there is a true intimation of the future in a school photograph from 1927 where Bourgeois has scratched out her own dead-centre face (apparently loathing a new haircut). This acute destruction turns the image into an enigma. Sex, suffering, motherhood, entrapment in the home, or by a man, or by children: all the acute power and mystery of her stupendous figures in cloth, latex, tapestry, wax and steel, her stuffed and limbless mannequins, woefully punished, deformed and pitied, have their inkling in the tip of that teenage needle.

Bernadac delicately implies that Bourgeois’s mother was sick for many years before Sadie’s arrival, possibly with emphysema, though we never discover precisely what. Nor is there any explanation of her father’s sudden death at 66 in a Paris clinic, barely remarked upon in Bourgeois’s diaries. And how exactly did she come to be married within 19 days of first meeting the American art historian Robert Goldwater in 1938, and why did she not set sail directly with him for New York? Bernadac glosses over it all: they were “very much in love”.

Within months, Bourgeois had returned to France on a family visit, where she adopted a three-year-old orphan, seemingly worried that she was not yet pregnant. Michel arrived by sea in 1940, accompanied by a nurse and refusing to disembark in New York, poor child, just six weeks before Bourgeois gave birth to her son, Jean-Louis. Dyslexic, farmed out to boarding school, eventually finding work as a building superintendent, Michel died suddenly in 1990. Bernadac does not tell us how or why, though public records must be available.

Discretion, prudence, professional tact: all these virtues mar this biography

Discretion, prudence, professional tact: all these virtues mar this biography

A third son was born 15 months later; how readily this invokes so many of Bourgeois’s female figures, weighed down by life and offspring. All three Goldwater sons were renamed Bourgeois in the 1950s out of fear of antisemitism and taken to France to escape the policies of Senator McCarthy. Bourgeois claimed to have been investigated by McCarthy several times. Bernadac’s acknowledgment that there is no evidence of this at all is tucked away in an anxious footnote.

Indeed the author keeps so dutifully behind the lines she has been granted that direct quotations from Bourgeois dominate the entire book, too often padded out with Bernadac’s own weak restatements. She scarcely ever puts her head above the parapet. This is a shame, as Bernadac is surely right – for instance – to believe that Robert Goldwater was an extraordinarily supportive husband, although Bourgeois barely mentioned him after his sudden death in 1973. The love letter reproduced here is extremely beautiful, yet Goldwater has almost no presence in this book.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

For a time, Bourgeois was in love with Alfred Barr, first director of MoMA. The extracts from her diaries are passionate, irate and astonishing. If there was the slightest reciprocation from this monkish intellectual, Bernadac is not telling us, any more than what happened with the many other men in the book. It is as if readers, and curiosity, are beyond her brief.

Almost the most vexing lacuna concerns Jerry Gorovoy, artist, companion, keeper of the flame. Bernadac quotes from Bourgeois’s diary of their journey to Italy in 1981. Someone called Mark Snyder turns up on the trip and Bourgeois is so appalled by the “sudden violence” of the situation that she is afraid of having a heart attack. Is he Jerry’s lover? Is this another betrayal? Who on earth is Synder? He exists only in one sentence, unexplained and never mentioned again.

Bernadac is stronger on art than biography. She understands why Bourgeois sidestepped all discussions of influence, despite the obvious connection between her exorcisms and the totems and fetishes witnessed through her husband’s directorship of the Museum of Primitive Art, as it was then known. In 1947, Bourgeois even created a tall metal prong to “get rid of” a rival artist named Catherine Yarrow. As Bernadac observes, Bourgeois hammered nails into the place where her chest might be, warding her off like an African sculpture.

That Bourgeois was frightening is well attested, a queen bee in a brownstone buzzing with awed acolytes. The sculptor Gary Indiana once described Bourgeois during her Sunday salons as a “hilarious terror”. Most of the tributes published in her lifetime suffer from servility, and even so long after her death this biography is still too timid. Bourgeois’ art is almost paraverbal in its directness and universal emotion; none of its meaning is obscure. Bernadac even takes her title from one of Bourgeois’s female torsos, headless and stumped, fitted with a terrifying knife, as if too respectful to come up with her own. The contrast turns out to be exemplary: between this dutiful book, with its careful quotations and unanswered questions, and the fierce life and art of this raging genius.

Knife-Woman: The Life of Louise Bourgeois by Marie-Laure Bernadac, translated by Lauren Elkin, is published by Yale University Press, £30. Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £27. Delivery charges may apply

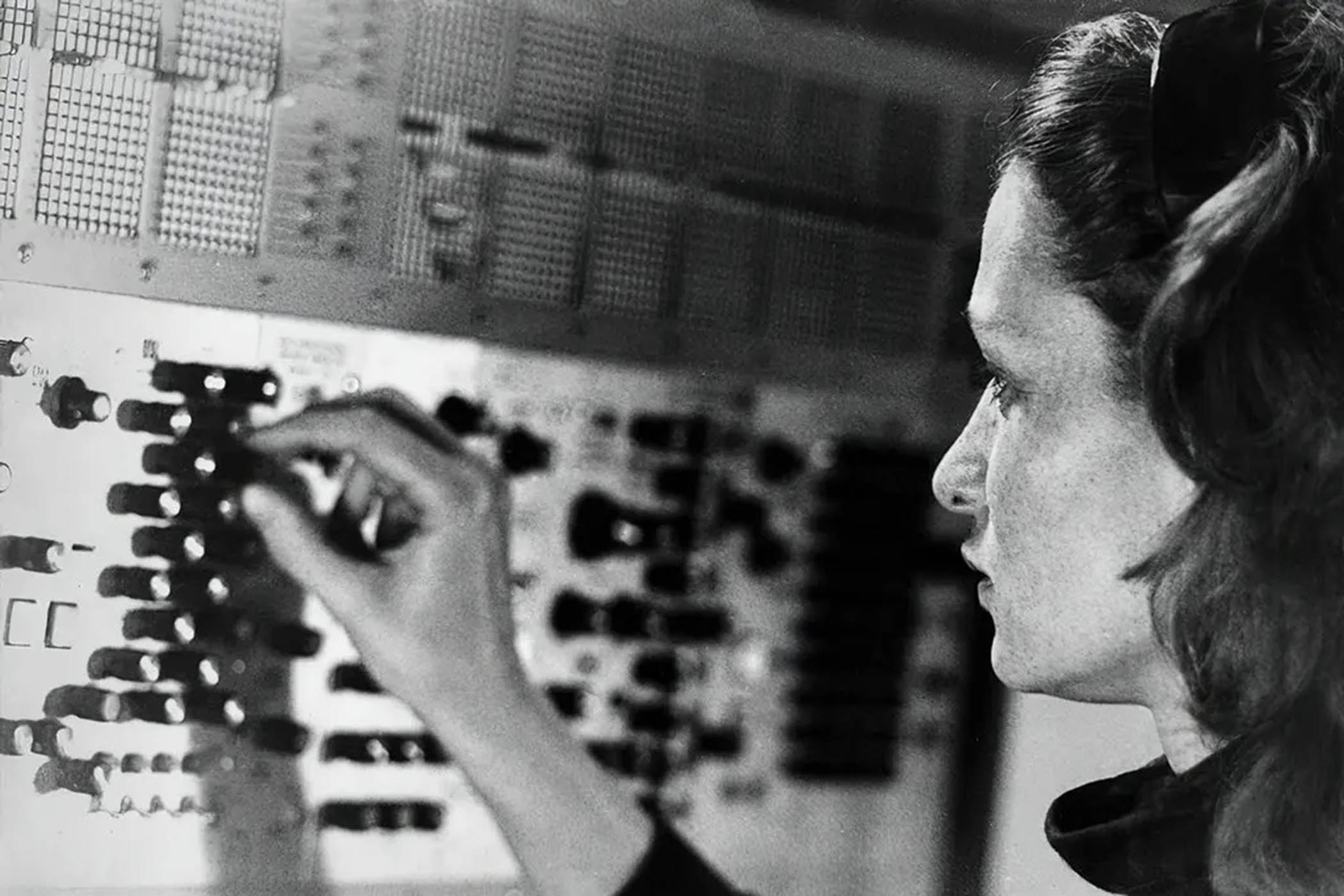

Photography by Raimon Ramis/Louise Bourgeois Archive via Sipa Press/Alamy