In 1983, when Mark Haddon turned 21, his parents asked what he would like as a birthday present. “I said art materials. They bought me a pair of monogrammed gold cufflinks. I lost one and I don’t think Mum ever really forgave me.” This reminiscence appears as one of several wry footnotes in the vivid memoir by the writer, best known for his 2003 novel The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Taken in isolation, that footnote is a rueful anecdote, but in the book’s wider context it represents something sadder and darker, another recorded example of a childhood endured without love or understanding.

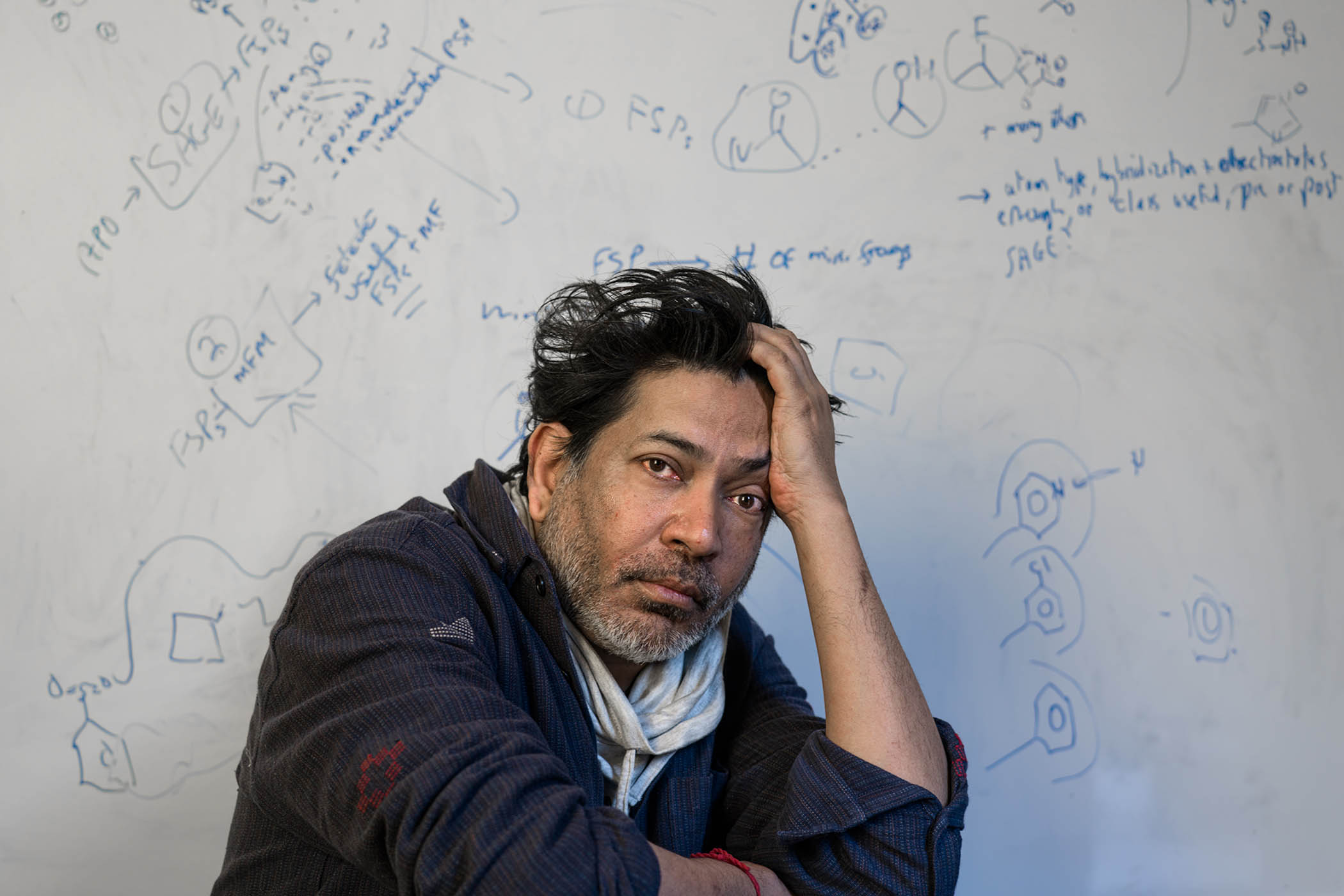

Haddon, in the opening pages, bills Leaving Home as “an exorcism”. It is unusually structured: he darts back and forth in a largely non-chronological way between childhood incidents and other consequential life events up to the present day, and it is illustrated throughout, scrapbook style, with photographs, memorabilia, ephemera and Haddon’s own striking artwork. The book brims over with anxiety, empathy and a kind of zinging, cleansing innocence. Despite being an atheist, Haddon is firmly in the mould of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress character Mr Valiant-for-Truth. There are monsters under every bed, and in the head too, as Haddon details his autobiography – one of extreme phobias, mental and physical health issues, and self-harm – with hyperactive humour and wincing honesty. (A selfie taken of the stitches needed for a cut arm as recently as 2024 is especially unsettling.) Thankfully there is also room for happiness: the sustenance of a long marriage, children, a hugely successful creative career and the satisfaction gained through helping others, from Haddon’s involvement with community service volunteers and the Samaritans.

A memoir is a slippery fish. What to include? What to leave out? Why write one at all? Yet for whatever reason the compulsion is there, often emerging once parents are safely dead, as Haddon’s are. Their deaths form some of the most poignant passages of Leaving Home: Haddon captures the blankness and ferocity of older age, and duty performed without love. The genre of memoir is itself highly subjective, impressionistic: forensic on certain points, hazy on others. (The 1970s, a period to which much of the book refers, is ripe for evocative, nostalgic references, from Babycham to Blue Peter.) Haddon repeatedly emphasises the fragmentary nature of his memories, which refer to a time when he was “often profoundly unhappy”.

‘There are monsters under every bed, and in the head too’: an example of the artwork from Haddon’s book.

Born in 1962, he grew up in a comfortable modern house in Northamptonshire with a younger sister, Fiona, to whom the book is dedicated, and his candour in including details from her life means that in some ways this is as much her memoir as it is Haddon’s. Materially, the siblings wanted for little; emotionally there yawned a deep, distressing abyss. Haddon’s father was an architect, self-made, from a working-class background, having displayed a talent for draughtsmanship during war service. His acute awareness of his own lack of education meant that Haddon was singled out – as the oldest and a boy (“to say I was the favourite would imply actual liking”) – for an academic path, which led to boarding school (Uppingham) from the age of 12, then Oxford. At school, Haddon was once caned until he bled through his pyjamas for taking the blame for a minor infraction. He stresses that the situation was much worse for others. The effects of relentless sadism – an enduring hallmark of the elite English boarding system – have been similarly explored in other recent memoirs such as Richard Beard’s Sad Little Men: Private Schools and the Ruin of England and Sebastian Faulks’s Fires Which Burned Brightly.

His mother, “an ardent Brexiteer avant la lettre… she believed that working women were the cause of unemployment”, seems to have spent most of Haddon’s childhood lying down in a darkened room. In later years she, like Haddon’s father, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, drank heavily. The couple were clearly psychologically estranged from each other, so how could they parent their children? Haddon doesn’t spare them, or us, from explicit details. The deceased can’t be defamed, only reckoned with. As Haddon writes: “What does it mean, the injunction not to speak ill of the dead? Which dead?”

Obsessed with science from childhood, Haddon is fascinated by the workings and failings of bodies – his own as much as others. (He had a triple heart bypass in 2019 and suffers from long Covid). Similarly, his enthusiasms – be it immersion in literature, music, art, a run or a river swim – are infectious, from an analysis of Georges Perec’s 1975 novel W: or the Memory of Childhood to his first experience of hearing the compositions of Benjamin Britten.

Every memoirist is asked if the experience of putting it all down is cathartic. In reality, it closes some wounds while opening others. Haddon eschews a conventional author photo for a self-drawn portrait sporting an earring. This is significant: as a student, Haddon had his ear pierced. His mother’s response was: “Only inadequate men have earrings.” In the same week, his sister was approached by an old friend in the pub who said: ‘“I’m so sorry to hear your brother is now a homosexual.” Rebellion against one’s upbringing can last a lifetime.

Leaving Home: A Memoir in Full Colour by Mark Haddon is published by Chatto & Windus (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £21.25. Delivery charges may apply

Related articles:

Photograph and illustration courtesy of Mark Haddon

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy