From bravura fiction to playful poetry, great lives to graphic novels – these are the best books of 2025, selected by The Observer’s team of editors and critics. And if you’re looking for children’s recommendations, here is our guide to the year’s best books for young readers.

FICTION

Flesh by David Szalay (Jonathan Cape, £18.99)

The 2025 Booker prize winner is a tale of masculinity, money and migration. Beginning in the 1990s, it contains nine snapshot-like episodes in the tumultuous life of István, who grows up in Hungary, spending time in juvenile detention and in the army before moving to London and eventually joining the ranks of the super-rich. István’s interior life is out of bounds, and David Szalay’s prose is so spare it’s barely there. That may sound like an austere reading experience, but the effect is thrillingly addictive, with a central character whose curiously passive nature is at odds with the high drama of his narrative arc.

Will There Ever Be Another You by Patricia Lockwood (Bloomsbury Circus, £16.99)

Reading this novel is an experience of disorienting novelty and sensory overstimulation – like walking into a funfair having just sustained a minor concussion. In her distinctively comic style, Patricia Lockwood recreates the chaotic absurdity of the 2020 lockdowns (“People were up at three am, contemplating the purchase of apple-flavoured horse deworming paste”) and the alienating strangeness of being ill (“The light hurt, as if she were evil”). You won’t read another book this year quite like this.

The Benefactors by Wendy Erskine (Sceptre, £18.99)

Wendy Erskine’s Belfast is a city of voices. More than 30 of them swell the pages of her terrific debut novel, disclosing their innermost fears and desires while making reference – often only glancingly – to the dark incident at the story’s heart: the assault of a teenage girl, Misty Johnston, by three local 18-year-old boys. Amid the cacophony, several key characters take shape, including that of Misty herself, made vivid by Erskine’s gift for capturing the rhythms and idiosyncrasies of their respective internal worlds. By the second half, this hurtles along with the pace of a thriller.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai (Hamish Hamilton, £25)

Kiran Desai took 20 years to write this sprawling, 700-page epic about love and family, a time in which she says she “vanished into an ocean of stories”. The story follows Sonia Shah and Sunny Bhatia, two young Indians working as writers in the US who meet on a train years after their grandparents’ failed attempts to matchmake them. Their romance unfolds over the following years, circling ideas of colonialism, belonging, work, ambition and familial estrangement. Desai adds to this a rich tangle of subplots that give the reader the feeling of having lived many lives.

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (Fitzcarraldo, £12.99)

Georges Perec’s 1965 novel Things: A Story of the Sixties was less concerned with its central couple, Jerôme and Sylvie, than their beautifully furnished surroundings. Here, the Italian writer Vincenzo Latronico updates the book for the era of flat-lay breakfast shots on Instagram and the sort of half-hearted activism that has the main aim of being noticed online. Anna and Tom are freelance digital creatives, haunted by their own digital avatars, who they can never live up to. Excellently translated by Sophie Hughes, it is an all too recognisable snapshot of a generation that wants to be original, just like everyone else.

Endling by Maria Reva (Virago, £20)

The unlikely collision of Ukraine’s underground matchmaking industry and endangered snail conservation fuels this deeply original novel, which takes a kidnap-inspired road trip through Ukraine at the time of Russia’s invasion. Maria Reva was inspired to write the book after a passing comment made to her sister about the subservience of the women in her native country. She writes as though powered by a jolt of adrenaline, and as a result the story is constantly shifting underfoot. Endling conjures the deeply online sense of the darkly funny material that emerges from unprecedented times, as churning events whip past at warp speed.

Fun and Games by John Patrick McHugh (Fourth Estate, £16.99)Coming-of-age comedies don’t come any funnier or more intelligently written than this outstanding first novel from John Patrick McHugh, whom Sally Rooney has credited as an influence. Set over one summer on a remote Irish island, it follows a hormone-addled school-leaver, hungry for sex but even hungrier for acceptance, as he strives to make the starting XV of his Gaelic football team amid the fallout of a socially ruinous sexting fiasco involving his own mother. With warmth and wit, John Patrick McHugh has us rooting for the beleaguered protagonist, even as we cringe at his unerring knack for self-sabotage.

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Fourth Estate, £20)

Like Americanah and her story collection The Thing Around Your Neck, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dream Count is set between Nigeria and the US. Where those earlier books eyed American mores from immigrant vantage points, her first novel in more than 10 years is a bumper compilation of middle-aged life experience, built around the friendship of three Nigerian women whose lives haven’t panned out as imagined with respect to marriage and motherhood. With its light-footed dialogue, witty satirical flourishes and generous social portraiture, Dream Count offers the thrill of time spent in the company of richly imagined flesh-and-blood characters.

On the Calculation of Volume 1 by Solvej Balle (Faber, £12.99)

In this first part of Solvej Balle’s septology, decades in the making, the most ordinary details of a woman’s life in rural France – the sound of a boiling kettle, birds in the garden – are supercharged with tension and mystery due to the extraordinary predicament in which she finds herself: she is stuck inside the 18th of November, unable to progress to the 19th, and nobody – including her husband – can help her out. Balle has published six out of seven volumes in Danish, the first three of which came out in English this year, and book one, translated by Barbara J Haveland, is a superb scene-setter.

Helm by Sarah Hall (Faber, £20)

A master short-story writer and undersung novelist, Sarah Hall writes fiction in which language and landscape are equally animate. In her new novel, she breathes life into Britain’s only named wind,: Helm:, the north-easterly that blows down Cumbria’s Cross Fell. The capricious, witty, puckish voice of Helm is heard across the ages, as we meet a cast of characters who fall under its spell: a Neolithic shaman, a present-day meteorologist, a 19th-century couple getting frisky in a hot air balloon. If there is an elegiac quality to this novel, written during an accelerating climate crisis, there is also a ferociously exuberant energy, not least in Hall’s restless, expressive, irresistible prose.

The Director by Daniel Kehlmann (Riverrun, £22)

GW Pabst was the Austrian film director who fled Germany for Hollywood after Hitler came to power but then, without intending to, ended up back there making wartime films under the Nazis. His story is told by the endlessly inventive German novelist Daniel Kehlmann (author of the marvellous Tyll) not as a straightforward recounting but a sly, shapeshifting entertainment that manages to be both tragic and tricksterish at the same time, while asking uneasy questions about art and political compromise. Louise Brooks and Leni Riefenstahl have memorable walk-on parts, while a cameo from Joseph Goebbels brings a whiff of sulphur to the proceedings.

Every One Still Here by Liadan Ní Chuinn (Granta, £14.99)

Much of the coverage of this short story collection focused on the identity of its pseudonymous author – but is it so surprising that a writer frankly addressing the still-open wounds of Northern Ireland’s bloody sectarian conflict would choose to remain out of sight? What’s more notable is the astonishing skill on display. In precise, direct prose, the half a dozen stories anatomise a post-Good Friday agreement generation caught between the forward momentum of their lives and the backward pull of the past. Whoever they are, Liadan Ní Chuinn is a writer to watch.

NONFICTION

John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs by Ian Leslie (Faber, £25)

Instead of fading over time, Beatles songs take on a richer colour. The effect of Ian Leslie’s John & Paul is that a song we thought we knew suddenly sounds even better. This is a book that offers not only a lesson in listening (again) but an enthralling narrative of friendship, creative genius and loss. At its centre is the songwriting partnership of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and the unprecedented peaks the two of them scaled in remaking popular music in Britain. You may find it impossible not to be awed by their achievement all over again.

Attention: Writing on Life, Art and the World by Anne Enright (Jonathan Cape, £20)Anne Enright is best known as a novelist, but this collection of 24 of her best essays from across the past decade demonstrates how adept she is at the form. Among the subjects she addresses are life (Enright’s family history; how society and fiction control women’s bodies), art (the work of writers including Alice Munro, Toni Morrison and James Joyce) and the world (the Honduras cocaine trade; her native city of Dublin). Enright’s writing has a sense of searching, as though you are thinking along with her – a style that renders her insights no less brilliantly sharp.

Children of Radium: A Buried Inheritance by Joe Dunthorne (Hamish Hamilton, £16.99)

Narrated with the twists and turns of a detective story, Children of Radium is a family memoir that records Joe Dunthorne’s discovery of just how little he knew of his German Jewish heritage, and his grandmother’s childhood escape from the Nazis. His journey starts when he finds a 2,000-page unpublished memoir by his great-grandfather Siegfried, a scientist who worked at a secret chemical weapons laboratory near Berlin before he and his family left for Turkey. As revelations and ambiguities mount, the book plays out as a tangled investigation of complicity, courage and cowardice, oscillating between potential indictment and mitigation.

How to End a Story: Collected Diaries by Helen Garner (Wiedenfeld & Nicolson, £20)

The Australian writer Helen Garner seems to be finally getting her due. This year, she co-wrote a book reporting from the mushroom murder trial and won the Baillie Gifford prize for this collection of her diaries, spanning from 1978 to 1998. As in her court reporting and fiction, Garner has a way of telling it like it is in her diaries, and by publishing her innermost anxieties and furies while she’s still alive, her frankness and stubborn refusal to dress up the truth makes for a record of a life that, despite its heft (more than 800 pages), feels urgent on every page.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This by Omar El Akkad (Canongate, £16.99)

From its agonising opening pages, this short but immensely powerful book by Egyptian-American author Omar El Akkad (American War) is essential reading for anyone in the west grappling with the horrors of Gaza and other conflict zones that are far enough away to put out of our minds. El Akkad asks us to look back at the present from the future, where the distance in time allows us safely to “acknowledge all the innocent people killed in that long-ago unpleasantness”. It’s a potent conceit at the heart of a fierce and riveting piece of writing.

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry (Jonathan Cape, £18.99)

Sarah Perry cared for her father-in-law in his final moments: David Perry, the ordinary man of the book’s title, died just nine days after his diagnosis of oesophageal cancer. The author draws the last weeks of his life in such vivid detail that he starts to take on a mythic quality. Her account of the messy, physical business of caring, and of how ordinary life rolls on even during unimaginable tragedy, captures both the strangeness of living and the inevitability of death.

A Year with Gilbert White: The First Great Nature Writer by Jenny Uglow (Faber, £25)

Our present glut of lavish, emotionally attuned nature writing owes a debt to Gilbert White, an 18th-century curate who documented his Hampshire garden in his nature journals, The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. Jenny Uglow revisits 12 months of his entries as he records, with awe, sightings of “sweet weather”, “fleecy clouds” and the northern lights “flaming red and vast in the night sky”. Uglow neatly draws a line from White to the present, demonstrating his profound impact on nature writing, what of the natural world has been lost to the climate crisis, and the wonder of how much beauty still remains.

This Is for Everyone by Tim Berners-Lee (Macmillan, £25)

The creator of the world wide web, who gave his creation to humanity for nothing, Tim Berners-Lee is vastly more influential than he is known. Weaving his own history with the backstory behind his invention, Berners-Lee rails against the deterioration of the internet as a whole, describing how authoritarian governments, grasping tech companies and their billionaire owners have sullied its early promise. But as the book’s title suggests, this is a call to arms – one that outlines how we can fight for the future of the internet instead of succumbing to the swamp of slop surrounding us.

The Power and the Glory: A New History of the World Cup by Jonathan Wilson (Abacus, £25)

Placing the tournament within a social and political framework, Jonathan Wilson expands our understanding of the World Cup to show how it offers reflections of moments in history: from its 1930 origins, when Fifa sought an international audience for the sport, resulting in a disaster-struck inaugural contest in Uruguay, to West Germany’s triumph in 1954, a moment of postwar global reintegration. Wilson also gets into the growing “haggling and skulduggery of the bidding process”, where autocratic nations seek to launder their reputations in order to host – an honour with almost as much glory as actually winning the trophy.

All Consuming: Why We Eat the Way We Eat Now by Ruby Tandoh (Serpent’s Tail, £18.99)

What shapes our eating habits in the age of online recipes and viral food trends? Why do we all suddenly go out and buy harissa, or queue en masse for chocolate-covered strawberries? In this witty, incisive exploration of our appetites, Ruby Tandoh ranges from TikTok food reviewers to medieval cookbooks via Elizabeth David and Victor Hugo Green. It could have been an ambitious mess, but in Tandoh’s hands, it’s a compulsive, opinionated delight. The chapter on bubble tea is as good as any piece of food writing you’ll read all year.

The Age of Diagnosis: Sickness, Health and Why Medicine Has Gone Too Far by Suzanne O’Sullivan (Hodder & Stoughton, £22)

Are we a society that is sicker than ever, or are we instead turning healthy people into patients? The neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan examines a subtle but crucial shift in the ways we see sickness and health, wherein diagnoses for conditions such as long Covid, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and allergies have grown exponentially, providing fertile ground for medical disinformation to flourish. Delicately walking us through a handful of patients affected by conditions including autism and Lyme’s disease, O’Sullivan uses her own clinical experience to question our dogmatic age of overdiagnosis, overmedicalisation and overdetection.

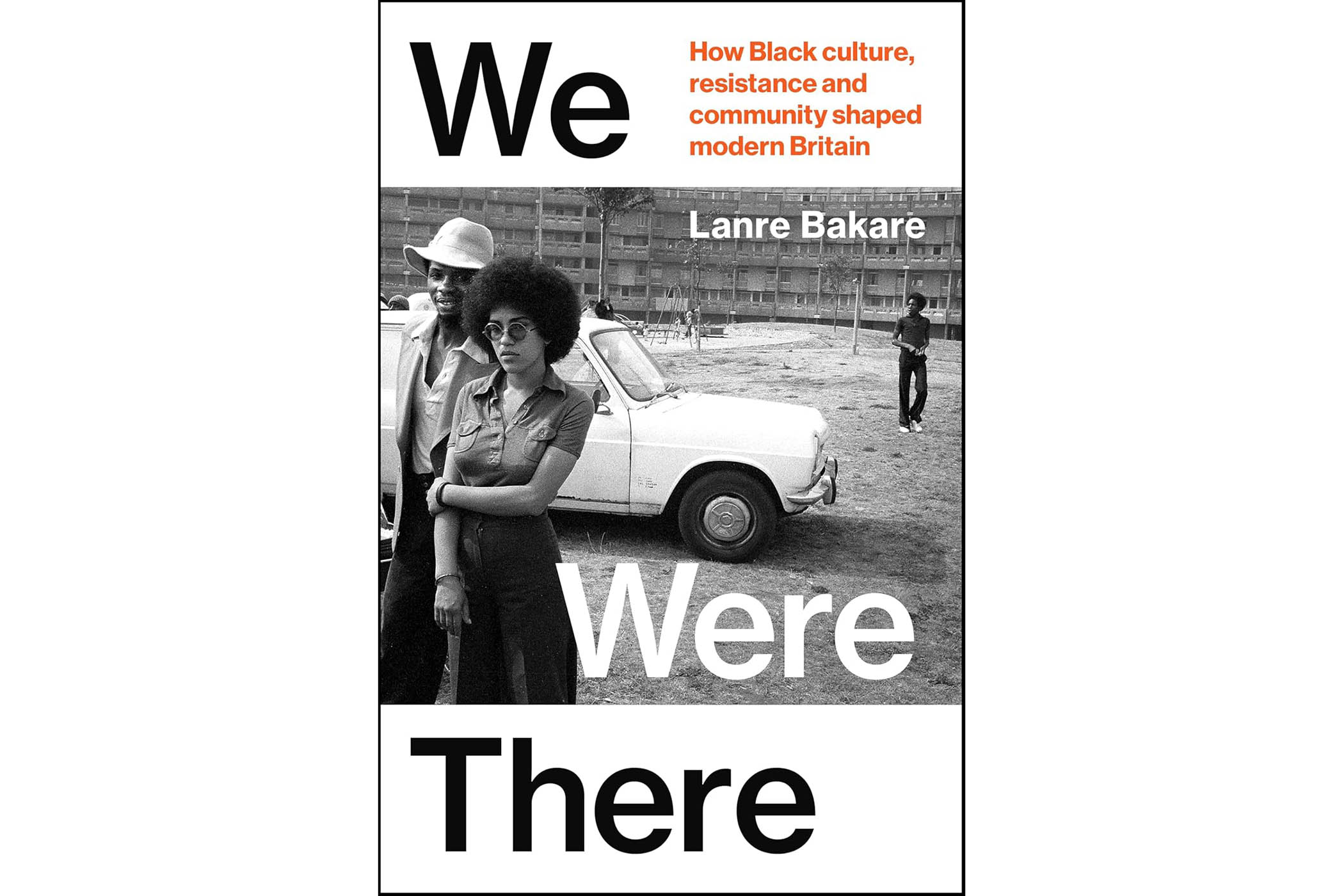

We Were There: How Black Culture, Resistance and Community Shaped Modern Britain by Lanre Bakare (Bodley Head, £22)

What if the contributions of Black Britons to the nation’s history were not simply overlooked but purposely obscured? Focusing on the 1970s and 80s – when, the author argues, modern Black Britishness was forged – Lanre Bakare unearths forgotten stories of black participation in cultural movements, restoring the true tapestry of British culture. In doing so, We Were There skilfully brings together diverse examples of Black people’s wide-ranging influence on the UK. If these stories are only told in isolation “they can be dismissed as curiosities”, writes Bakare, “that don’t alter our sense of what constitutes British culture”.

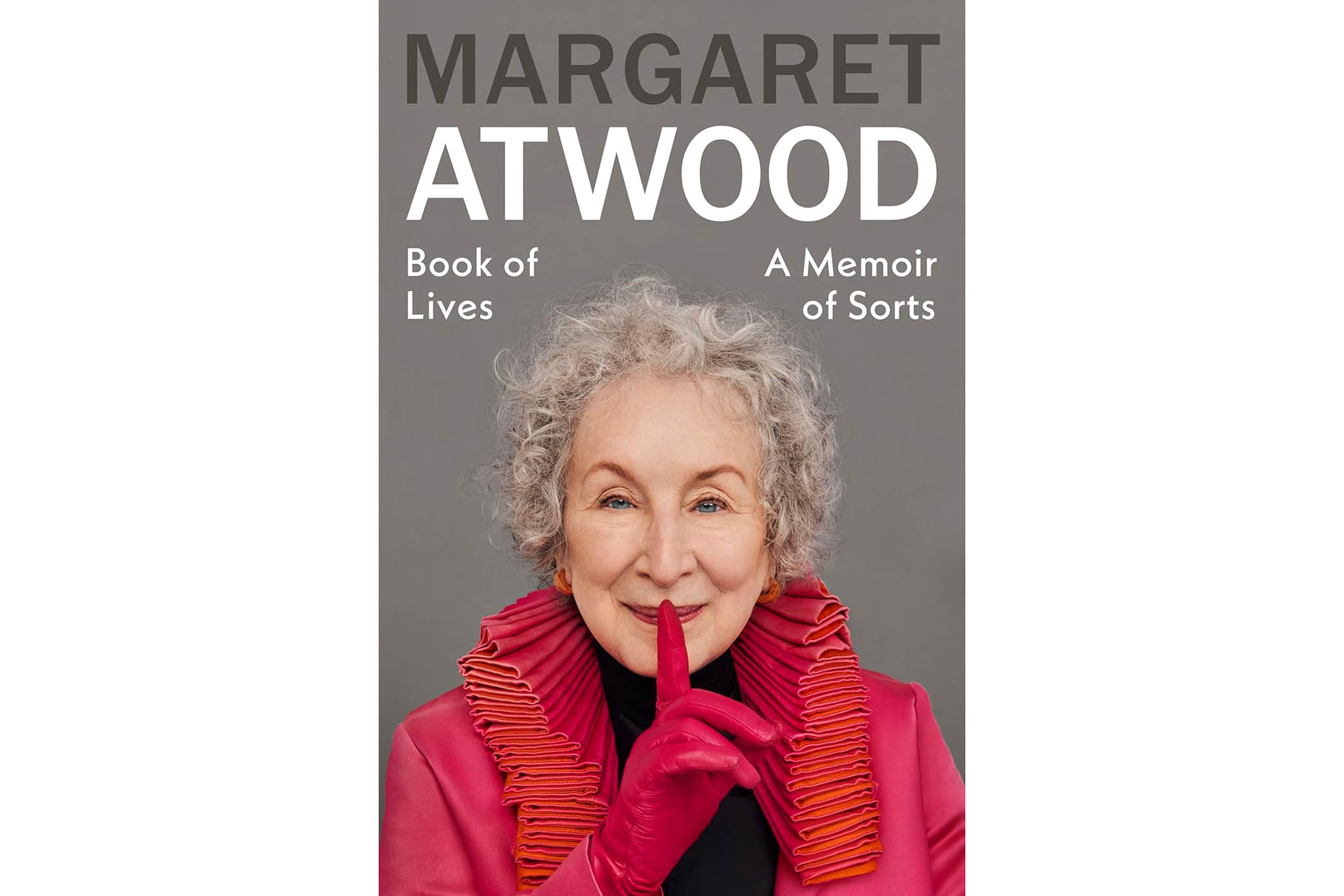

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood (Chatto & Windus, £30)

Margaret Atwood’s memoir opens with a two-page list of more than 50 works of fiction, poetry and essays that she has written. It’s an early hint of the many lives she has lived, which are recalled in this fat and satisfying book – from an early childhood spent in the woods during freezing Ottawa winters to the “intoxicating” four-line poem she composed in her head as a teenager that turned her – over the course of strolling across a football field – into a poet. Atwood revisits the phenomenal success of The Handmaid’s Tale, as well as the instructive failure of the first novel she wrote, a near-plotless work influenced by Samuel Beckett. But the most striking and moving passages reflect on her relationship with Graeme Gibson, her dear, lifelong companion, who died in 2019, as Atwood was in the throes of her career’s remarkable second act.

POETRY

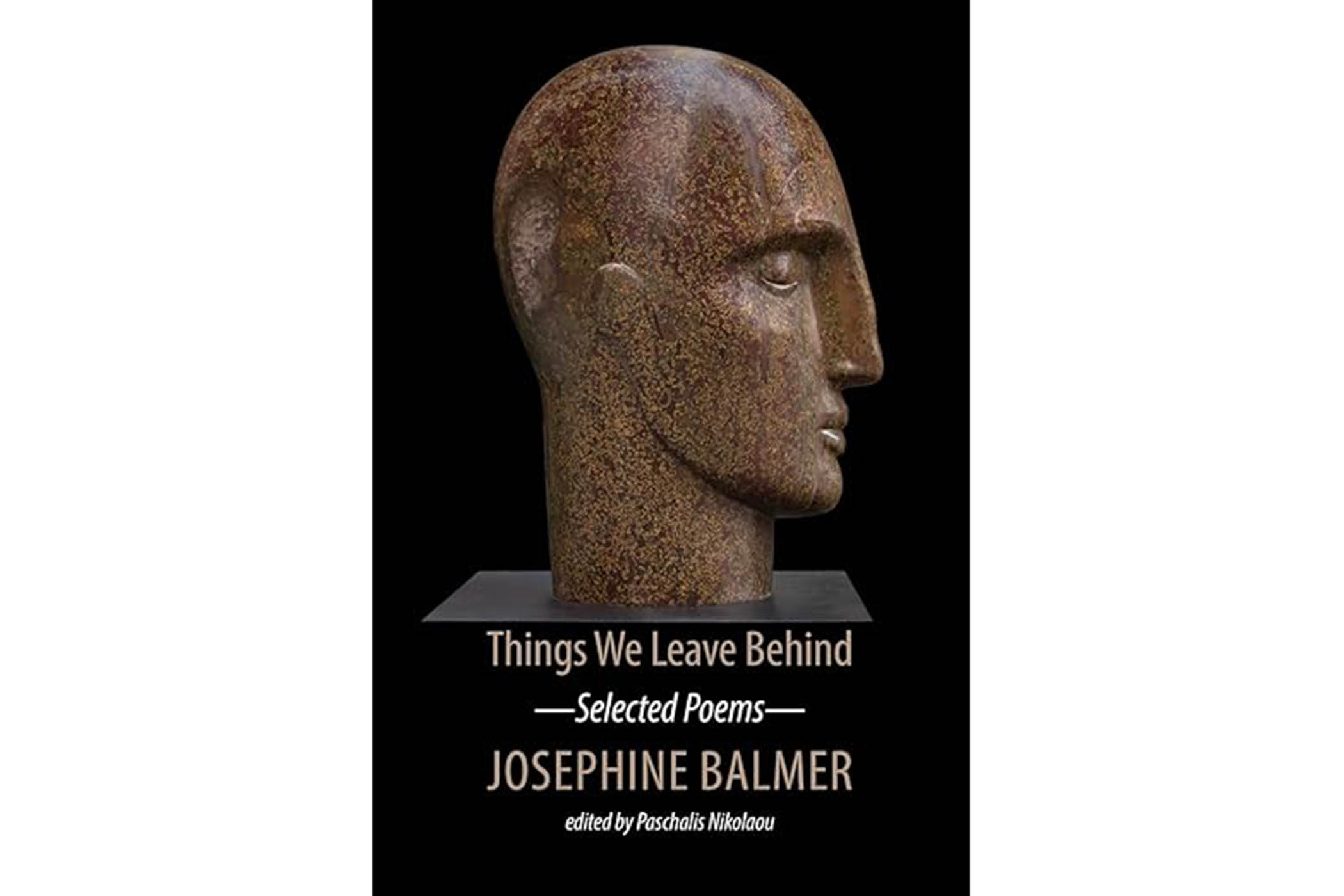

Things We Leave Behind: Selected Poems by Josephine Balmer (Shearsman, £14.95)

It’s well known that some wines improve with age – the same applies to certain poetry books. Josephine Balmer’s Things We Leave Behind is drawn from five collections and four decades of work as a classical translator, and its riches reveal themselves over time, like the fascinating archaeological finds she excavates from the earth. The longer one sits with Balmer’s meditations on mortality – her unsettling proposition about our own “snug” plot in the soil – the more one is seduced by her promise of stillness, that “wrench of nothingness, / stark lacunae we all must someday face”.

The Xenotext: Book 2 by Christian Bök (Coach House Books, £13.99)

In this audacious work – arguably the world’s first example of “living poetry” – the poet and Leeds Beckett University professor Christian Bök chronicles the completion of his 25-year experiment, in which he used a “chemical alphabet” to encode a sonnet into the genome of the almost indestructible bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans – which can survive radiation, acid, freezing and even outer space. Miraculously, the microbe “writes” a poem back. Although his text is shadowed with apocalyptic gloom, Bök stokes a romantic idea: that poetry might live in more than just our hearts, perhaps even outliving humanity itself.

Wellwater by Karen Solie (Picador, £12.99)

Karen Solie was deservedly named, alongside the brilliant Vidyan Ravinthiran, as joint winner of best collection at the 2025 Forward prizes. The judges rightly praised both poets’ “philosophical depth” – though Solie’s honesty and humour are equally admirable. The landscapes of Wellwater are riddled with fungicide and glyphosate, and as “terminator seeds” cough up things “more dead than alive”, Solie confesses: “I don’t know how to make this beautiful … Can we go back?”

New Cemetery by Simon Armitage (Faber, £14.99)

In his first full-length poetry collection since The Unaccompanied in 2017, the poet laureate makes a marvellous if macabre return (think pickled cadavers and putrid intestines) with a haunting and moving sequence of poems that draws on the wonder of moths (each poem is named after a species) and the sudden death of his father in 2021. Simon Armitage also teases humour from his spry tercets, making the experience rather like playing hide-and-seek between tombstones.

GRAPHIC NOVELS

Cry When the Baby Cries by Becky Barnicoat (Jonathan Cape, £25)

Becky Barnicoat may be in love with her new son, who arrives thanks to IVF, but she’s also lonely and exhausted. Here she records her experiences with bracing candour in visual form, employing brilliant pastiches and checklists, and mercilessly sending herself up throughout. From leaking breasts to dubious stains, no subject is off limits in this very funny, sardonic book – an analogue antidote to the Instagram version of motherhood.

Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy by Paul Karasik, Lorenzo Mattotti and David Mazzucchelli (Faber, £20)

In 1994, Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli created a graphic adaptation of Paul Auster’s City of Glass, but only now – in a book overseen by the novelist before his death last year – is the cartoon form of his trilogy of stylish postmodern detective novels at last complete. Sketched in black and white, the stories have a concise, noirish, cinematic feel, even as they play hugely inventive games with pace and scale. This single-volume edition is an instant classic that will be read for decades to come.

Illustration by Luke Best

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism.