Two summers ago I walked past a street sign leading to my local park and stopped dead as I noticed two shiny googly eyes pressed into the “O”. They were pudgy and freshly shimmering and the size of chocolate coins. A thin felt-tip nose and a trembling smile had been drawn in there, too, both the blue-green colour of a faded tattoo. I thought about the laugh that was made by the people who did this – “Heh! Ha!” – and got annoyed. I thought about picking the googly eyes off with my fingernails but it was broad daylight and, as ever, I had to consider how insane my behaviour would look in public if a stranger perceived me doing it. Very insane. Instead I decided to do the normal thing and walk a different route to the park for a few weeks until the barrage of wind and rain and nature might have knocked them away. Then I would know peace.

But, no. The eyes multiplied. They were pressed on to the maps inside my Tube carriages and studded onto the policeman cut-outs they put in particularly rough branches of Superdrug. They were on the back of bus seats, gazing back at me, or thumbed onto posters and adverts for pie. Soon after, Labubus started to peer at me, too, their little clawed hands gleefully outstretched as they grew grubby and evil on the straps of various backpacks and keychains and bags. “Heh!”, they seemed to say. “Ha!”

The world – a dark and horrible place where quality of life has fallen down a flight of stairs in the last five years alone – is trying to raise a cheap little smile out of me. Why?

It is impossible to really know when googly eyes were invented, or why, but they’ve been here since you were born. The earliest reference to them is from the 1919 cartoon strip Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, where the titular Barney Google has, well, big white-and-black “google-y” eyes.

The plastic stick-on, zanily moving art-and-crafts-supply version became prominent in the early 1970s with the creation of Weepuls – those pompom-shaped creatures you get on bookmarks and stuck to the edge of office desktop monitors in the 1990s – which somehow sold in the number of 400m between 1971 and 2012. And then, of course, if you knew someone a bit tedious at university, you will be familiar with the concept of putting googly eyes on a cactus and giving it a name (“Hey, offer some of your beer to Spike!” “That’s great, man. Can we do the group project now?”) What I am saying is: googly eyes have been around.

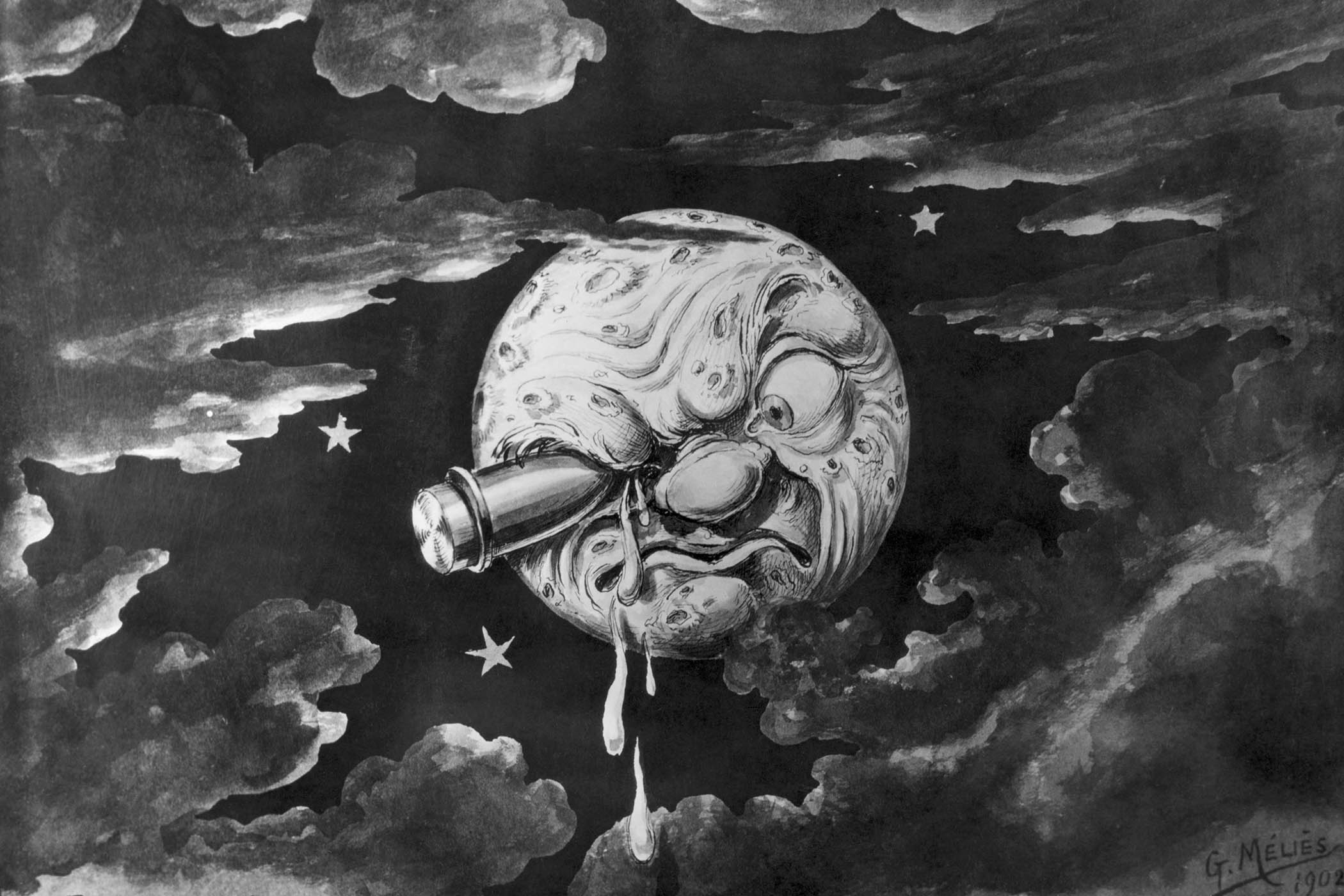

In 2013, there was a viral art project called “eyebombing” which encouraged the whimsical addition of googly eyes to public objects to inspire moments of “Heh! Ha!” in people’s day-to-days, but it stayed very much on a corner of Reddit until 2022, when everyone on earth watched Everything Everywhere All at Once at the same time and for some reason thought Ke Huy Quan’s character Waymond’s preoccupation with sticking googly eyes on washing machines was somehow important and good.

A scene from Everything Everywhere All At Once

After that, they started to turn up more and more on inanimate objects in the real world: fire hydrants, bollards, municipal plug sockets. A small semi-jokey protest in Boston led the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority to add googly eye-shaped stickers to the front of five of their trains (“As part of our ongoing efforts to bring moments of joy to our riders’ daily commutes,” a spokesperson said).

Last November, an Australian teenager was charged with property damage after fixing two of the things to a £68,000 sculpture known as the Blue Blob (the mayor of Mount Gambier described the act as “wilful damage to a valued public artwork,” and “inappropriate and disrespectful,” a reaction so joyless it has me on the side of the googly-eyer).

Related articles:

Now, eyes are peering from everywhere: every pizza logo is an anthropomorphic slice whistling a tune and looking at you, the new Anya Hindmarch x Boots collection is zanily multi-ocular, every TV ad is seemingly a monster made of bold-coloured fur with no features but eyes, to help you feel less dread about paying a utility bill (British Gas) or how little you’ve contributed to your pension (Nest). After the peering hype of the Labubu, there are dozens of pretenders, including Mirumi, a sinister handbag-clasping doll-bot. Go to the pub and cheers someone: eyes, eyes, eyes.

We react to the horrors around us with ‘micro-joys’

I have been trying to understand the eyes since they started following me around. I was trying to remember when the wider adult population was last so unashamedly enraptured by “cute”, and couldn’t shake the Beanie Baby craze of circa 1996-1999: the royal purple Diana baby, the tag protectors, the iconic photo of a divorcing couple on their knees in a court, sorting their floppy toys into two little sad piles. The Beanie Baby Bubble, as hindsight allows us to refer to it, didn’t have the right texture, though: people were muscling children out of the way of toy-store queues, sure, and deliriously outbidding each other on an early version of eBay, but because they thought the toys were no-miss investments rather than due to any feeling of whimsical warmth (they were wrong).

The closest thing we have to these now are Jellycats, which thankfully people seem to collect just because they genuinely want an avocado with feet and a smile on it instead of for financial reasons. Their popularity seems bafflingly outsized, though: occasionally you will walk through central London and have to cross through an incredibly well-behaved queue for something and 15 minutes later, when you get to the front of it, you realise they’re all there just to buy a little toy that’s a boiled egg. What’s happened to make us do that?

Well, everything. Rent has gone up, the unemployment rate is near a five-year high, you have to enter into a Faustian pact with Tesco’s Clubcard to get groceries for anywhere near a normal price. The other day a friend said: “I heard we’re going to have a world war. Probably this year!” with the same bored gossipy tone you might employ to talk about a neighbour’s divorce. Yesterday, I put some fancy teabags back on the shelf, because I couldn’t quite justify to myself that I would drink all of them before the bomb evaporated my body. Economically we are living through a scarcity of joy.

Eyes appear on everything from bollards and bins to designer bags (as seen at Anya Hindmarch's London Fashion Week SS18 show)

This isn’t the first time the economy has gone “a bit frowny-face”, and it isn’t the first time we’ve responded to it by telling it to smile. Walt Disney’s animated characters caught the American psyche during the Great Depression, where movie-going remained popular as an escape from the hard reality of eating dust for breakfast and dinner (there is not currently a section about this at Disneyland).

In Japan, the aesthetic culture of kawaii (meaning “cute” or “loveable”) started around 1975, with the popularity of the curvy-bubbly calligraphic style maru moji and the launch of Sanrio’s Hello Kitty, mutely gazing out of stickers and pencil cases and notebooks. Popular enough during the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Hello Kitty had a huge revival in the mid-90s – the middle of Japan’s “Lost Decade”, when the value of the yen collapsed and a number of major financial powerhouses went bankrupt – when Kitty White was joined by San-X’s Tarepanda.

As the millennium threatened to break everyone’s computers all at once, a final wave of cute poked out from behind the rubble of the banks: Pikachu and all the other original 151 Pokémon I can still name for some reason, as well as the doomed-to-die keyring pet, Tamagotchi. We want soft-edged adverts and playful little faces when the economy is as anxious as we are.

Enter “Heh! Ha!” Since 2008, when all those recessions started, there has been the economic concept of the “lipstick effect”, noted by Leonard “Estée” Lauder when detailing the increased sale of lipsticks in the wake of 2001’s terror events and subsequent worldwide financial disasters. The consumer trend towards very small luxurious goods – lipsticks, mascaras, underwear – increases in times of economic duress (when masking became common during Covid, and lipstick necessarily became less important as a result, the principle was deferred over to complicated nail art, now sometimes referred to as the “nail polish index”). We react to the horror around us with micro-joys. A Labubu smiling from a handbag is spiritually indifferent from doing a really stunning eyeshadow look because you can’t afford to go on holiday this year.

Then, of course, there’s the robots that are coming to eat our faces. The six-wheeled delivery robots that Amazon and other companies use are necessarily anthropomorphised with cheerful Wall-E-style features so we (the humans) don’t attack them and tip them over. In America, where they have supermarkets the size of counties increasingly staffed by eerie shelf-stacking robots, some of the larger machines have been retrofitted with googly eyeballs to make them less startling and weird.

Pareidolia – the psychological pattern-recognising phenomenon that makes us see faces in clouds or on the tops of pints of Guinness – means we’ve seen a rock or a tree or a drainpipe smile back at us. Now, we’re using it against ourselves, to make the robots look more comforting while they emotionlessly steal our jobs.

It doesn’t feel good. When I heard that rumour about a cleansing war that was coming I did think: “Well, at least I won’t have to worry about council tax.” But if I can’t take some comfort from a lamp-post smiling at me, and I can’t take comfort from the actual reality of the world, either, then what really is there?

A friend recently came back from the bathroom looking pesky. “What?” I said. “Give me some.” No, he explained. Above the second urinal over from the door. You’ll see it when you’re in there next. A third of a pint later and I was staring up at what he’d done: freshly affixed to the cistern, just starting to gently dew with beads of condensation, was a sticker of Everton goalkeeper Neville Southall from 1997.

I noticed this pattern of behaviour among the men around me as they turned into the deep part of their 30s in a way where they start getting very defensive if you playfully try and snatch their cap off their head: at weekends, after a few Guinnesses and perhaps a not-as-good-as-you-think-it-is watch of a Dulwich Hamlet game, they get a primal urge to put up stickers in pub bathrooms. Vinyl custom-made numbers they’ve printed out themselves. Circular-coloured dots that came free in the packaging for a £60 T-shirt they just bought. Or, the most enduring of the genre, vintage Merlin stickers of footballers they worshipped in their youth.

I stared up as Neville, in an iridescent with the Danka sponsor across the front, beamed down at me, hair brushed back, the grass behind him a shade of green that hasn’t been achieved on turf since the millennium. “Heh!”, I thought. “Ha!” Between the urinal and the bar I’d bought a dozen stickers of Ray Parlour off eBay, ready to nestle in my wallet and be deployed whenever I am alone in a bathroom in a place where pints cost more than £7.

If the bombs don’t get us, the robots will. Perhaps this really is all we’ve got at the moment.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy