Who and what are we? Answering that question means searching our souls, looking at ourselves closely, the good and the bad. Can we nurture the good so that at some future point in the evolution of mankind, violence will, possibly, cease to exist? Maybe. But right now, violence is here. Inherent in our nature. It’s something that we do. It’s important to show that, so that one doesn’t make the mistake of thinking that violence is something that others do – that “violent people” do. “I could never do that, of course.” Well, actually, you could. We can’t deny our nature.

Violence is, for me, a part of being human. The humour in my movies is from the people and their reasoning, or lack thereof. Violence, and the profanity of life. Earthiness, if you want to be polite about it. Profanity and obscenity exist, which means that they’re part of human nature. It doesn’t mean that therefore we are inherently obscene and profane; it means that this is a real aspect of being human. It’s not good, but it’s the reality.

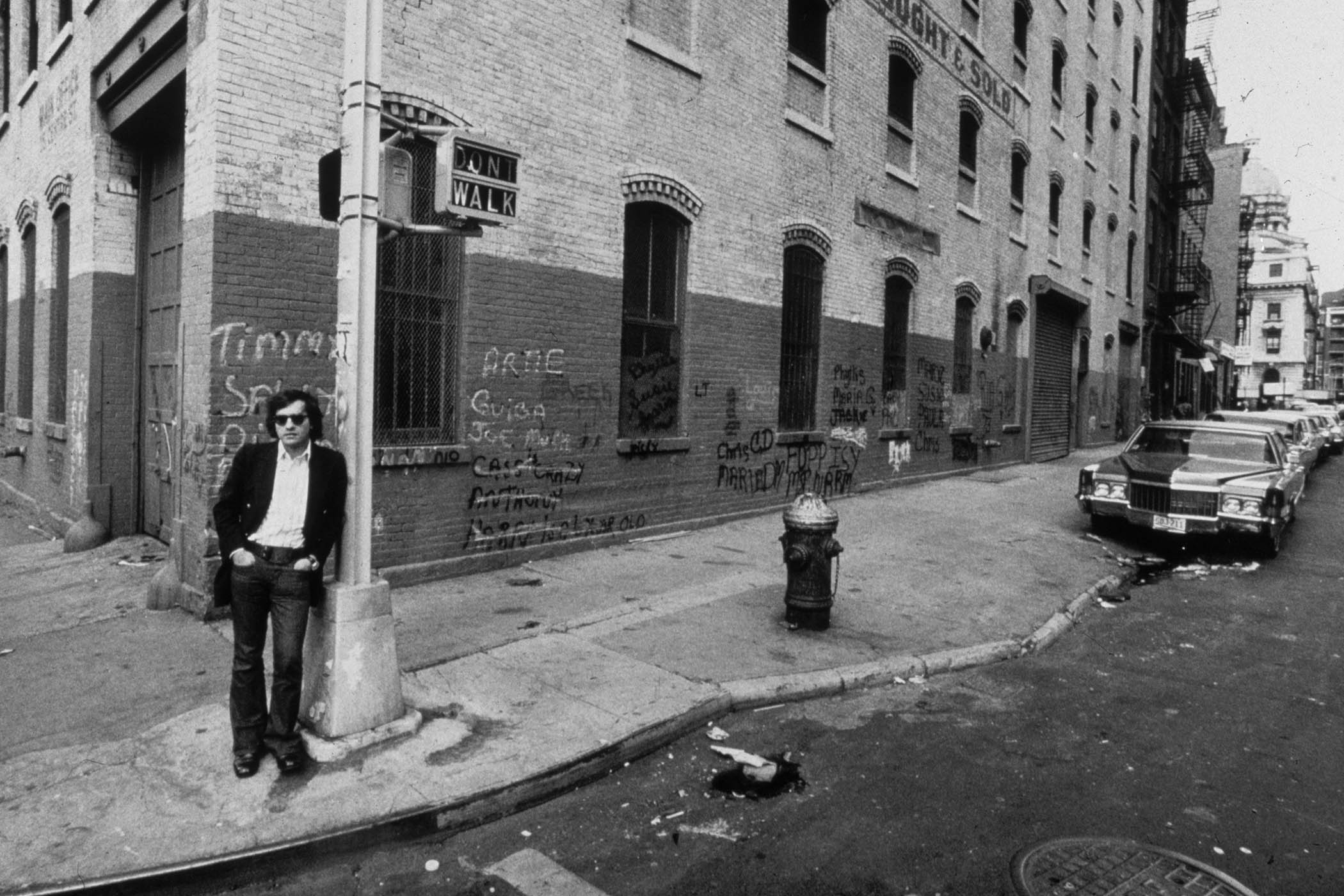

Some people don’t understand violence, because they come from cultures, or actually subcultures, from which it’s very distant. But I grew up in a place where it was a part of life, and where it was very close to me. Today, many people are growing up in very violent places. I’m not even talking about the parts of the world that are at war, which is a horror. Mass shootings in the US happen so often that we take them for granted. Never did I think that we would be facing such a reality, but we are. So, it’s an extremely violent life for a lot of people.

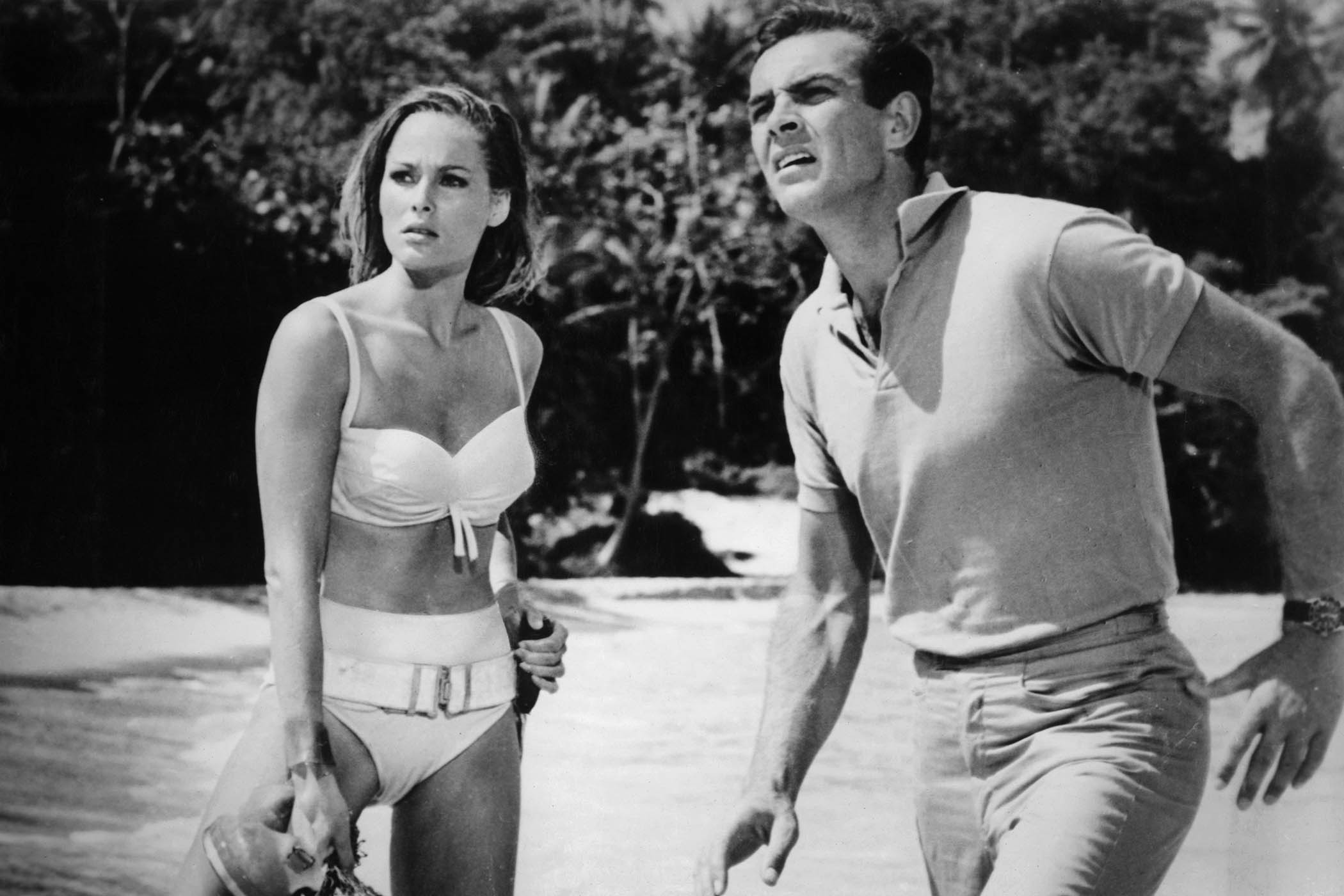

William Holden in Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, from 1969

In my case, the physical violence I saw around me and that I experienced was overshadowed by the emotional violence: in a way, that was even more terrifying. I think that there are two aspects to violence and its presence in my films. The major point is: who are we? Violence comes from within us; it’s part of the human condition. To deny that only prolongs the situation and puts off any way of reckoning with it. We have to face it in order to understand that it’s within our nature. I’ve encountered many people who are very sweet, and I wonder: what happens when they discover violence within themselves? Unless they’re prepared for it, it will come as a shock. Understanding that, and possibly overcoming its effects, is the key.

Back in the early 1970s, we were coming out of the Vietnam era and the end of old Hollywood. With Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and then The Wild Bunch (1969), everything opened up. Those were the pictures that spoke to us, not in a pleasant way.

About 20 years ago, I was in Washington with the Dalai Lama. I was speaking to a Tibetan monk who was travelling with him, and he said: “I saw your film Gangs of New York [2002].” I said: “Oh, I’m afraid that it’s a little violent.” And he said: “Oh, don’t be upset about it; it’s your nature.” I was suddenly very moved. Yes, it might be my nature. But then I have to deal with it. We have to know that we’re capable of it. That’s where we begin to understand it.

Every frame was teeming with emotional violence. You felt like it was going to explode. I could relate to that

Every frame was teeming with emotional violence. You felt like it was going to explode. I could relate to that

There was a writer who recently came to see my film Killers of the Flower Moon (2023). The film is based on a great nonfiction book by David Grann that reads like a novel. Around the turn of the 20th century, the Osage struck oil on their reservation. Pretty quickly, they became some of the richest people in the world. Then, of course, the white speculators, and swindlers, and opportunists, and thieves, and outright murderers descended. Some were “officially sanctioned”, you might say; most weren’t. They just smelled easy money. So, there was a concentrated effort to kill off pretty much all of the Osage community for their oil money, by every means imaginable: shootings, bombings, hard liquor, and slow poisoning; white men were marrying Osage women and then “helping” the women to die so they could inherit their property and their oil rights. It came to be known to the Osage Nation as the “reign of terror”, and with good reason.

I was talking to a famous writer and I said: “This man married this woman, they were in love with each other, they had children together... and then he started poisoning her. Is it possible we’re all capable of doing such a thing? It’s unimaginable.” And he said: “Well, if one person is capable of doing it, then we’re all capable of doing it.”

One can understand the violence in films, as a sort of heightened aesthetic experience, the way that Sam Peckinpah did in The Wild Bunch. The violence in that picture comes as a shock to the system, and part of the shock is the allure of it, the terrible beauty, the orgasmic release, so to speak. It’s extremely stylised, but somehow it reflects the effect and the exhilaration of real violence – the kind of exhilaration that the soldiers involved in the My Lai massacre probably felt. The Wild Bunch came out of the Vietnam era, and it really spoke to all the confusion, outrage and horror we were feeling as a country.

John C Reilly, Liam Neeson and Brendan Gleeson go into battle in 2002’s Gangs of New York

But for me, I don’t know any other way to shoot violence except as I experienced it. The ugliness of violence, the awkwardness, which [German director] Rainer Werner Fassbinder did so well in his early films – that was what I saw in my neighbourhood. But growing up there, I also had my own attraction to violence. That gets back to what the monk said to me about Gangs of New York. If you grow up around it, it’s not so surprising that you might develop some kind of attraction to it. Again, this is something that we have to understand and face in ourselves. We have to know and deal with that truth about ourselves.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In the neighbourhood I grew up in, there were always fights and they could be very exciting, but then there were killings. I didn’t witness any murders myself, but I knew some of the people who were killed, and that wasn’t funny, it wasn’t exciting and it wasn’t beautiful. I can appreciate the beautiful choreography of violence in the early John Woo pictures, in Zhang Yimou’s martial arts films, in The Grandmaster (2013) by Wong Kar-wai. But that’s ballet. It’s phenomenal, but it’s ritualised and extremely stylised, and it distances you from reality. That’s not a criticism yet I feel it removes you from the impact of actual violence. John Ford understood violence. So did Sam Fuller; he was an immensely powerful film-maker. Every frame of Fuller’s movies was teeming with emotional violence, and you felt like it was going to explode any second. I could relate to those pictures.

So, I find that when we distance ourselves from the experience of violence, we do ourselves a real disservice. It seals us off and, most dangerous of all, it creates the illusion that we can eradicate it, keep it at bay, and maybe even inoculate ourselves against it.

What we finally have to do is understand and embrace the violence in ourselves.

This is an edited extract from Scorsese on Filmmaking and Faith: A Conversation between Martin Scorsese and Antonio Spadaro (Sceptre, £14.99). Order a copy from observershop.co.uk for £13.49. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Jack Manning/New York Times/Getty Images, Allstar/Alamy, Collection Christophel/Alamy