For Mona Fastvold and Brady Corbet, film-making is life and death. Together they write and direct fearless movies that divide audiences but demand everyone listens. “It has to be deeply meaningful because it’s too hard if not,” says Fastvold. “If you don’t care about every frame, every moment of what you’re creating, then it’s just too challenging.”

“I know in the first five minutes of a movie what the last five minutes are gonna look like,” adds Corbet. “It’s so hard to make a movie. Why not attempt to make something pretty new?”

Their last film, The Brutalist, was a three-and-a-half-hour epic – including intermission – about a Hungarian architect’s path to and through post-second world war America. The couple wrote it together and Corbet directed, and last year it won three Oscars, including best actor for Adrien Brody. While the pair were wrapping up that film, they were in the thick of making their next, The Testament of Ann Lee, directed by Fastvold this time. The biopic follows the 18th-century religious leader Mother Ann (Amanda Seyfried) who founded the Shakers, a radical group derived from the English Quakers, and named because of the ecstatic, spasmodic singing and dancing that was part of their religious practice. The Shakers believed sex was the root of human suffering, and Ann Lee instructed her followers – small in number to begin with but reaching the thousands after her death – to renounce it.

Corbet says he and Fastvold were tired of stories about sex cults, and instead they set out to tell Ann Lee’s story without cynicism. “There’s always a turning point in these types of stories about religious or political leaders, where their ego takes over or they do something horrible or manipulative. With Ann it just never came,” Fastvold says. “I think that struggle and wish for paradise on Earth, as she would call it, is something we all are trying to create in everyday life for ourselves.”

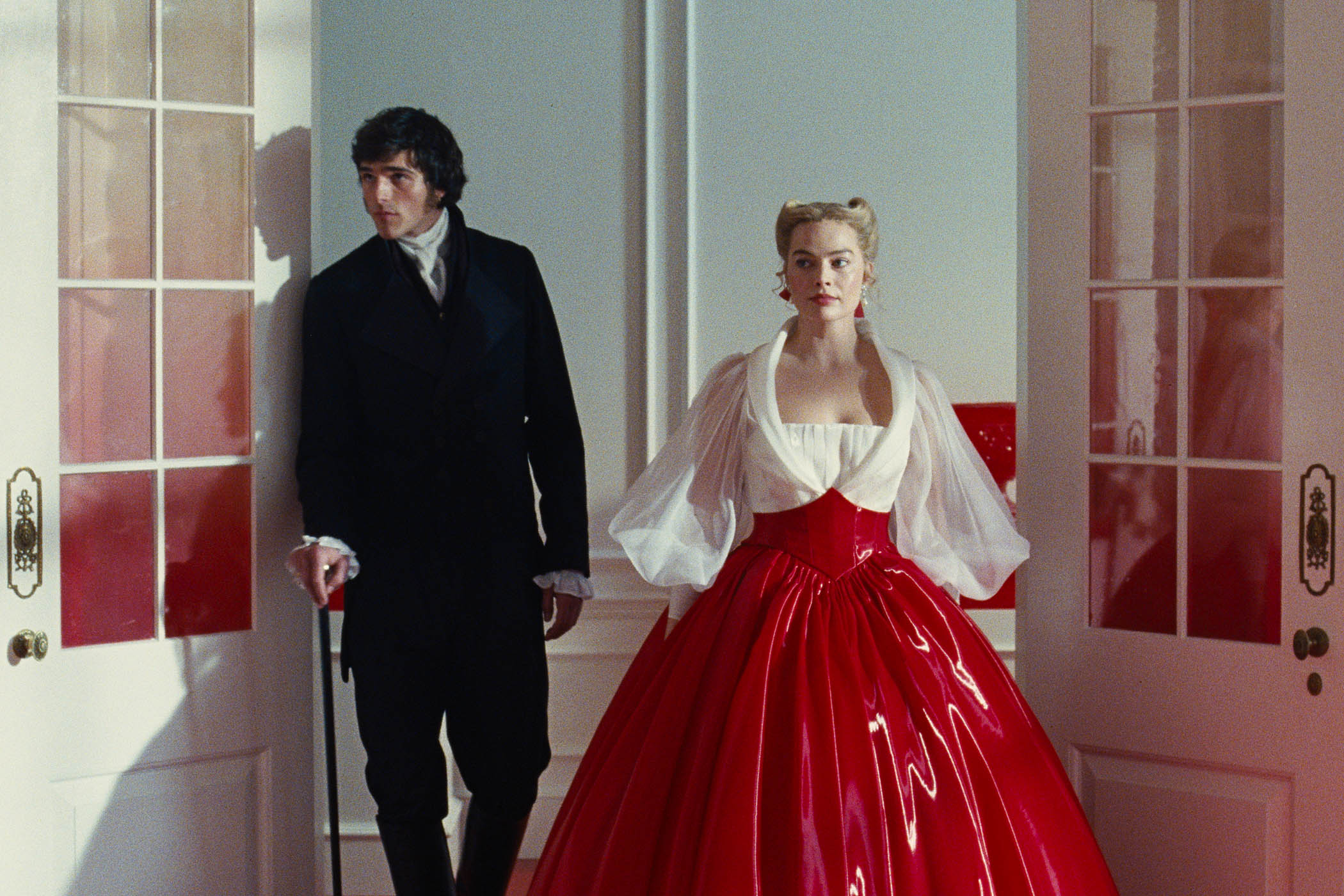

Amanda Seyfried, centre, plays the title role in the ‘ambitious, unusual’ musical The Testament of Ann Lee

We are speaking on a video call ahead of the film’s UK release. Fastvold and Corbet, 44 and 37 respectively, are at home in New York. where they live with their 11-year-old daughter. The couple are sitting side by side with a poster of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1986 film The Sacrifice tacked on the wall behind them.

Traces of Tarkovsky and his slow cinema can be seen in both Fastvold and Corbet’s long camera shots and dreamlike sequences, but The Testament of Ann Lee enters even stranger terrain. When Fastvold was researching the hymns of the Shakers and how they would suddenly burst into song, she realised the film had to be a musical. “That was my goal, for it to be so intoxicating and really pull you into it,” says Fastvold, who trained as a ballet dancer in her native Norway. “You’re spun around and thrown upside down. You’re not allowed to just hang back and look at the pretty dancing.”

There are several astonishing musical numbers in the film, as when a group rhapsodically beat their chests and their bodies tumble around one another like waves, or in a brutal, beautiful sequence in which Ann Lee gives birth and then loses all four of her children over a period of years.

It was vital to Fastvold and Seyfried that they captured this particular montage with truth and specificity; the midwife who appears in the scenes had come from delivering a real baby that morning. “We have umbilical cords that bleed and really exquisitely made prosthetics for vaginas and bellies. I spent a lot of time trying to create a great visual effect of breast milk squirting out of her nipple. All these things are very much part of the female experience that for some reason we’re constantly being kept from seeing,” Fastvold says. “It’s very dangerous, especially [in the US] when maternal health is completely under attack. We have to remember how this is how we are put on this Earth. There’s no other way,” she laughs. “Everyone’s been born.”

Over the course of their career, Fastvold and Corbet have come to believe that the only two real taboos are birth and death, and responses to this montage only support their theory. “We were told that 15 male critics walked out at Venice film festival during the birthing sequence and didn’t come back because they were very provoked and upset by it,” says Fastvold.

Provocation is what the pair are trying to achieve, and yet both are mystified that provoking audiences these days often seems to result in anger, not curiosity or excitement. “For us, a provocation’s purpose is to transcend,” says Corbet. “And we are looking for transcendental experiences, not only in our lives but in cinemas.”

‘We were told 15 male critics walked out at Venice festival during the birthing scene and didn’t come back’

‘We were told 15 male critics walked out at Venice festival during the birthing scene and didn’t come back’

Fastvold acted and danced as a child; Corbet grew up near a casting hub for child actors in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and had roles in films such as Thirteen and Thunderbirds as a teenager. The actor Christopher Abbott (Girls, Poor Things) introduced them after working with Corbet on the 2011 film Martha Marcy May Marlene. The pair began writing together on Fastvold’s The Sleepwalker (2014), which Corbet also starred in, and were friends and writing partners before becoming a couple.

They will usually write side by side in a process Fastvold describes as “very symbiotic”. “We talk for years about something before writing it, and then once we sit down and write, it’s kind of a faster process because it feels so obsessive. We work day and night until we have a first draft and then it turns into endless tinkering until the movie’s done,” she says. Do they find time for anything but work? They laugh. “It’s very bad. We work seven days a week,” says Corbet.

Fastvold adds: “We try to carve out time for our kid and she’ll tell us to put our phones away and not talk about work. She’s 11 but she’s pretty good at policing us now. But no, we don’t have a work-life balance. I don’t know what that is.”

Fastvold makes a comparison between film-making and architecture, pointing out that they like to avoid changes to the script after filming starts because it can be “quite dangerous to start messing with your blueprint while you’re building”. Much like The Brutalist’s stubborn architect László Tóth (Brody), who refuses to let his art be tainted by others, and Ann Lee, with her innocent vision of a better world that she clings fiercely to against all odds, both directors are resolute defenders of what they want to make, and how they want to make it. This results in ambitious, unusual projects that inspire discussion and feel brilliantly vivid in a sea of reboot and franchise churn.

Mona Fastvold with Amanda Seyfried, right, on the set of The Testament of Ann Lee

I left both films dazed from the experience of living totally inside another world, and they stayed with me for weeks afterwards. As a review of The Testament of Ann Lee in the New York Times put it: “When an artist takes a swing this colossal and stays true to their vision in every way, the resulting work deserves respect, and is always worth seeing.”

Yet the success they have earned has steered them not towards Hollywood, but in another direction. Both films were made in Hungary partly to maintain the same crew, and partly to avoid shooting in the US where, as Fastvold says, “half your budget doesn’t end up on screen”. They are baffled that, unlike in European cinema culture, it is the studio and not the director who gets the final cut.

“This is not a fucking advertisement, you know?” says Corbet. “Somehow the process where there are a million cooks in the kitchen interfering with what you’re trying to make has been really normalised in America. We want to be in dialogue with our partners, but it’s different to go through that process with a gun to your head.”

The Testament of Ann Lee and The Brutalist are risky projects. Both were financed independently and found distributors after premiering at the Venice film festival. This means both were made on an incredibly tight budget. “We have sequences here in Ann Lee that were made with a skeleton crew, and then we have days on backlots where we built massive things and had hundreds of extras, and so many goats,” says Fastvold.

“So many goats,” Corbet agrees.

Made for under $10m and earning more than $50m globally, The Brutalist was a rare example of an original story outperforming its budget. But Corbet is discouraged by the tendency towards critical pile-ons when films do stumble at the box office. “It basically just means studios are in a position where they have to just put out more [franchise] IP that they know is going to work. After a while, it’s like, how much cape and tights can you fucking watch?” he says. “I don’t have a problem with the fact that these things exist; my problem is that, at the moment, it seems to be the majority of the output. Even noir didn’t last this long. It’s been like 25 years of this shit, I’m ready for a new era.” They recently watched Harry Lighton’s eccentric biker “dom-com” Pillion – starring Harry Melling as Alexander Skarsgård’s mouthguard-wearing play thing – and loved it. “It’s just the most lovely romance, but with super hardcore sex,” Fastvold says happily.

In an interview on Marc Maron’s WTF podcast in 2025, Corbet revealed they earned “zero dollars” on the last three films they made. That fortune has changed with The Testament of Ann Lee – the film received finishing funds and the crew, including Fastvold, were able to earn a modest fee. But the money is not what motivates them, as Corbet’s next project shows. “I could have made my next film something more lucrative for our family if it was not NC-17 [rated 18 in the UK] and four hours long, but that’s a choice that I’ve made,” he laughs.

“We will never compromise on how we’re going to make films. It would be a wonderful surprise if they happened to be financially lucrative for us but that’s not really the goal,” says Fastvold. “We’re very privileged people. We have a cosy house and some days we drink champagne, others cheap prosecco.”

The Testament of Ann Lee is out in UK cinemas on 20 February

Photograph by Weston Wells for The Observer. Plus Searchlight Pictures

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy