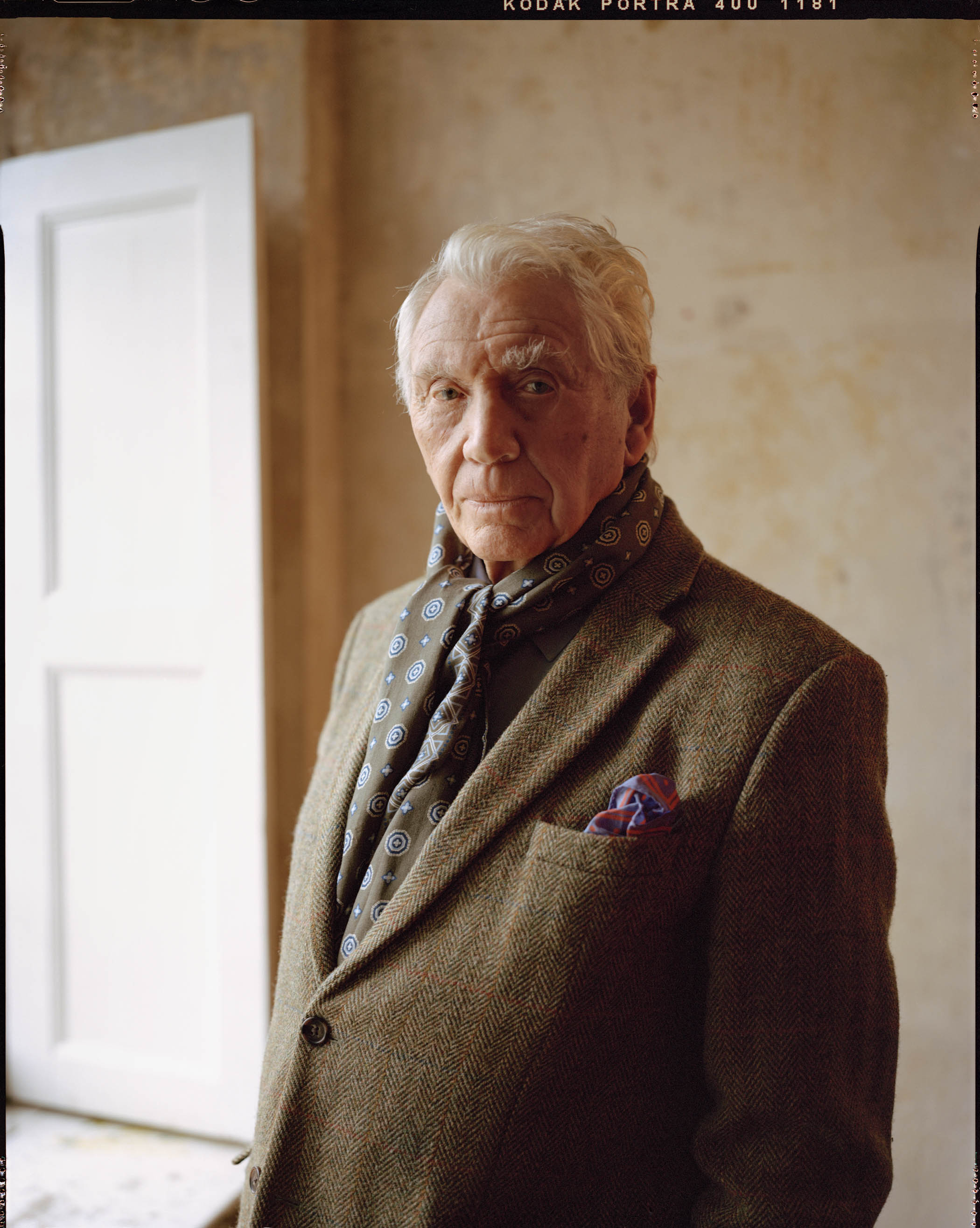

Portrait by Jane Hilton for The Observer

By dint of what they do and how they do it, there are some people whom we never envisage reaching a ripe old age. Back in the 1970s, few saw Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones making it to 82. But he’s a whippersnapper compared with the great photojournalist Don McCullin, who is now 90, though he could pass for 15 years younger.

In the days when Richards was risking oblivion with needles, McCullin was dodging bombs and bullets to produce some of the most memorable images of war in photographic history. Now in his tenth decade, he is impressively upright, immaculately dressed and strikingly handsome. With his thick silvery hair, full lips and pale grey-green eyes, he is a walking portrait, a photographer’s dream.

I meet him not far from his Somerset home at the Hauser & Wirth gallery in Bruton, which is staging an exhibition entitled Don McCullin 90 celebrating his work across seven decades – and coinciding with a show of his more recent photography at the Holburne Museum in Bath.

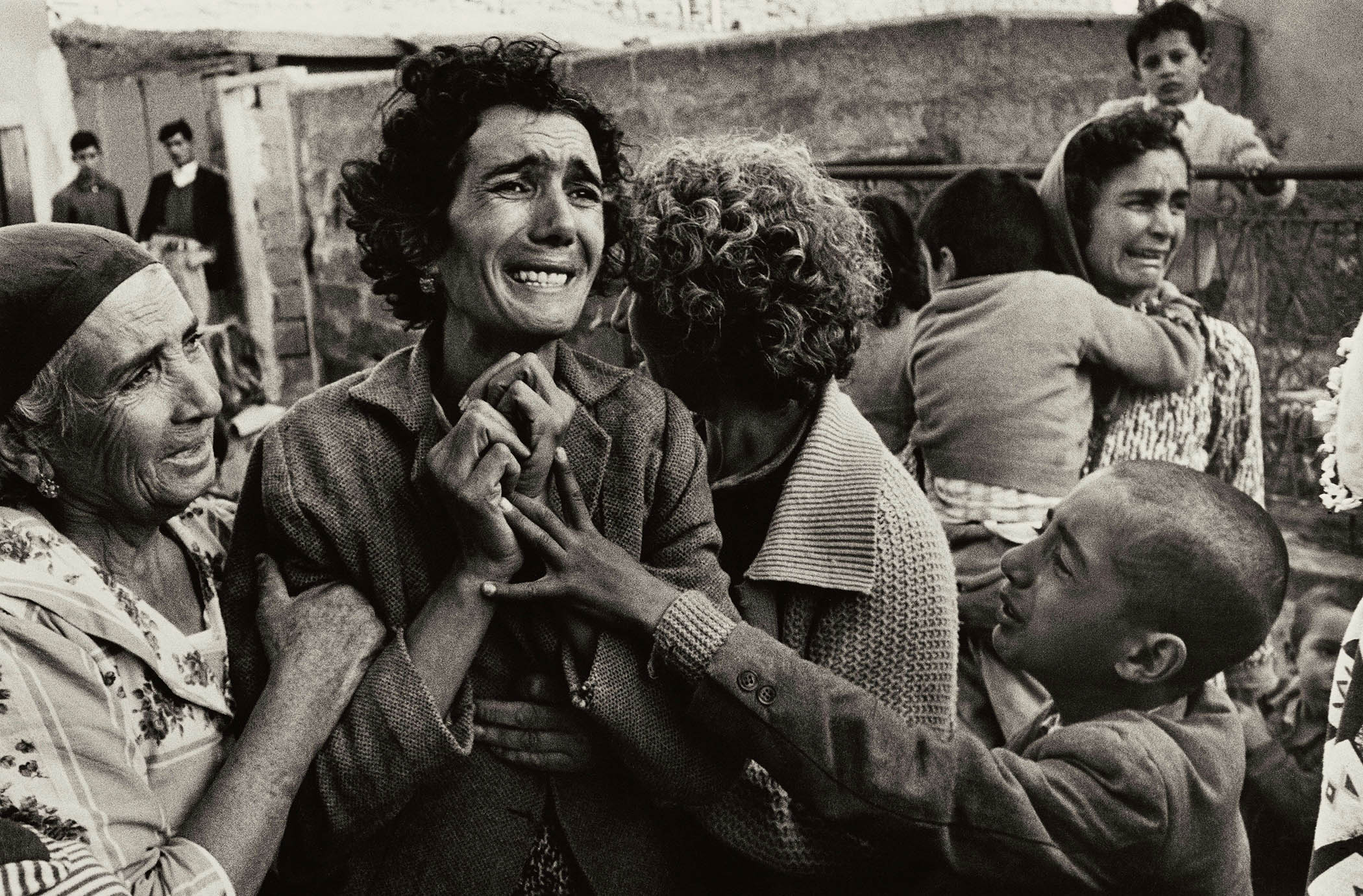

A Turkish woman mourns the death of her husband in 1964

If weeping widows have since become something of an editorial cliché, no photograph has conveyed the heartache and grief of sudden widowhood quite as hauntingly as McCullin’s 1964 shot of a Turkish woman whose husband had just been killed by Greek forces in the Cypriot civil war.

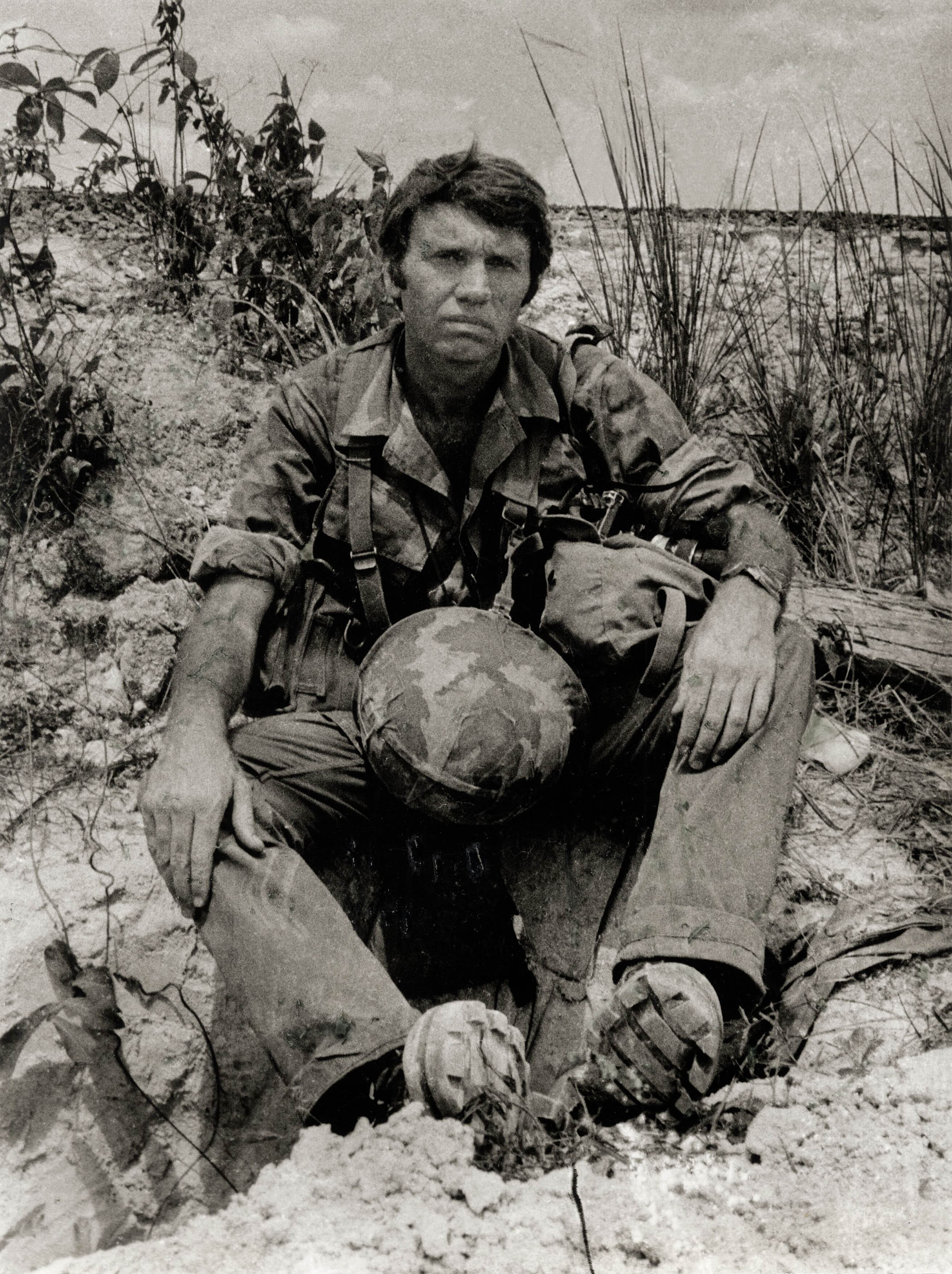

Nor has anyone ever captured the paralysing horror of shell shock as graphically as McCullin did with his 1968 image of a hunched US marine in the Vietnam war holding his rifle and staring blank-eyed into a mental abyss. So familiar are these portraits that they have formed a distinctive photographic style that has been much imitated but never equalled.

A shell-shocked US marine in Hue, Vietnam, in 1968

Yet he rejects the title of war photographer.

“I hate it,” he says.

This seems strange, given how frequently he went to conflict zones in the 1960s and 1970s, and he continued to do so – albeit less regularly – into this century. Cyprus, Congo, Vietnam, Northern Ireland, Biafra, Lebanon – wherever there was bloodshed, he was there with his camera in the belly of the beast.

By his own reckoning he was, for a long while, a “war junkie”, a type he knows well. “Vietnam was crawling with them,” he says. “Spooky people, dodgy people, all kinds of mavericks and gunslingers. Errol Flynn’s son used to have pearl-handle revolvers.”

Sean Flynn, a photojournalist, was killed in 1970 in Cambodia. “I got there a week after they were all captured,” says McCullin. “I didn’t want to be murdered with a shovel over the head at night in a jungle.”

Don McCullin in Vietnam in 1972

Of course, one way of avoiding such an outcome is by staying away from jungles and war zones, but that kind of basic logic has never seemed to hold much sway with McCullin. “My timing has always been good,” he says. “I think fate has been guiding me.”

Good timing is a relative concept. McCullin was injured by an explosion in Cambodia in 1970, though that did not prevent him taking a photo of the Cambodian paratrooper who’d received most of the impact of the mortar, as they were both ferried on the back of a lorry to receive treatment. The paratrooper died en route. As McCullin put it in his autobiography, Unreasonable Behaviour: “It could so easily have been my dead corpse rattling.”

Along with a healthy serving of good fortune, McCullin’s illustrious career has been a product of raw talent, hard work and enormous courage. Born in 1935, he grew up in poverty in a house in north London with an outdoor lavatory and a tin bath that he was allowed to use once a week. I mention that children tend to see their own conditions, however reduced, as normal. “Well,” he says, “I felt that I deserved better.”

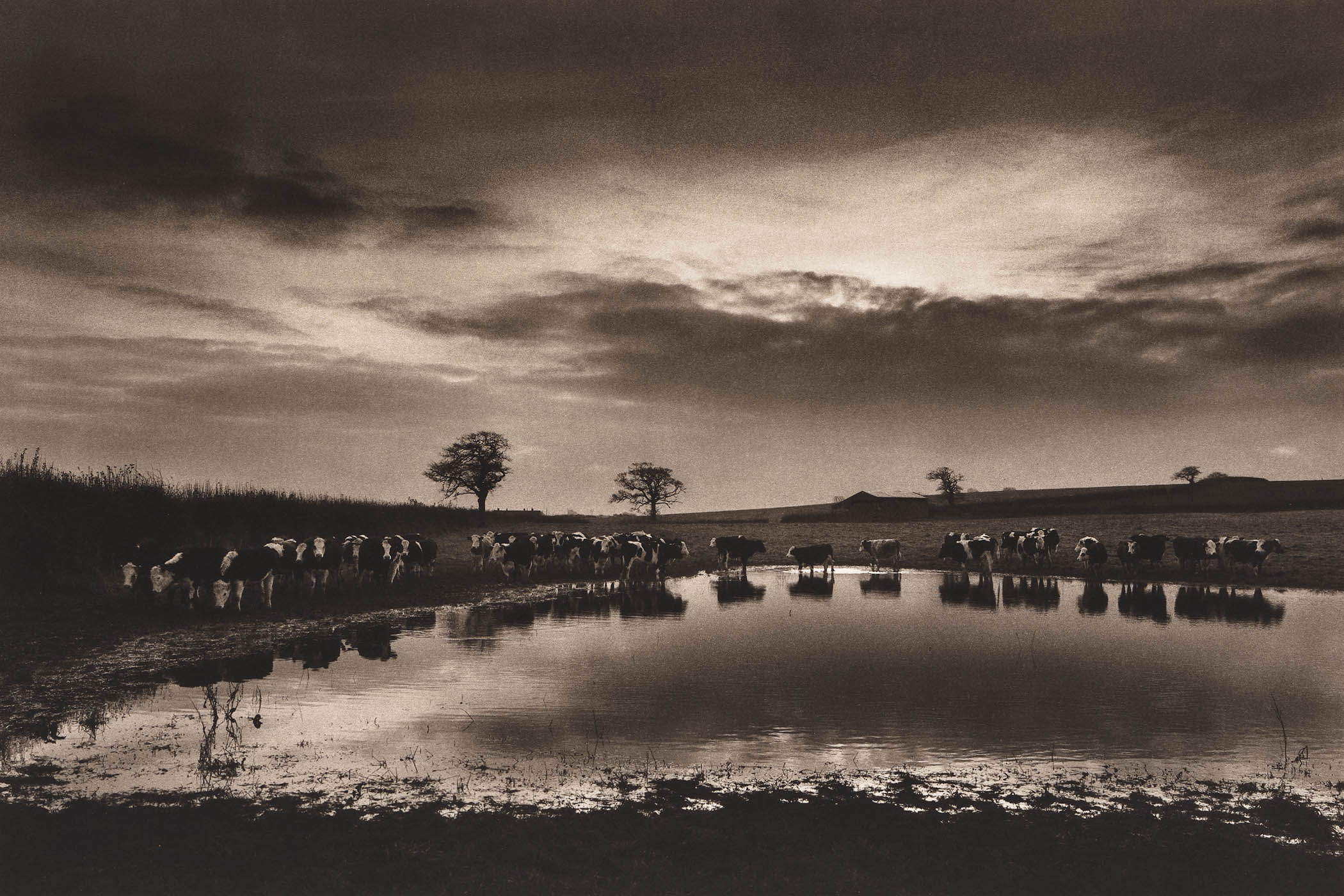

At the age of five, he was evacuated during the war to nearby Frome and sent to live with some farm labourers. He recalls begging his father to take him home when he came to visit. Despite his loneliness, he developed an abiding love for the countryside, another regular focus of his lens. His magnificent, austere Somerset landscapes are full of gnarled trees and glowering skies that speak less of peace and tranquillity than a psyche steeped in conflict and struggle.

McCullin’s shot of a gang in Finsbury Park, published by The Observer in 1959

His relationship with his mother was not close and his father died when he was 13. Leaving school at 15 without qualifications, he did a stint of national service before his first break in 1959, when The Observer published a photograph he took of a swaggering local gang in his Finsbury Park neighbourhood.

Dressed in sharp suits, they stood menacingly in the ruins of a derelict house. “Those boys had been involved in a gang clash,” he recalls. “A policeman had come to stop them, and another guy from an Islington gang stabbed that policeman at the end of my road. In those days, it was a capital offence to kill a policeman and he was hanged in Pentonville prison.”

That photo, which earned him £50 – more than five times the average weekly UK wage – was what McCullin calls “the first thread in the material of my life” and the beginning of a long association with Sunday papers, initially with The Observer and then the Sunday Times. In a sense, McCullin’s career was a happy accident of history. Owing to a particular alignment of technology and commerce, there was sufficient advertising revenue and editorial commitment in Sunday supplements to support the most ambitious era of photojournalism.

The other driving force was social mobility. McCullin was one of a number of notable young working-class people who made their way into the creative industries in the late 1950s and early 1960s and went on to gain international renown. He still speaks of his Finsbury Park origins with more emotion than he does of his close shaves with death. “I was ashamed of Finsbury Park,” he confesses. “I was ashamed of the way I grew up.” It was a place, he says, where violence was rife.

The photographer, now 90, at Durslade farm in Somerset

The irony, of course, is that he escaped violence to then travel the world documenting it in its most bloody and disfiguring form. Although not at first. In the early days of his freelance photographic career, he married Christine Dent, with whom he had three children, and lived in a small flat in Finsbury Park.

It was seeing Peter Leibing’s now iconic 1961 photograph of a young East German border guard jumping over a wire to escape to West Berlin that inspired McCullin to go to the city, despite The Observer’s lack of interest. The Berlin Wall was about to be built and McCullin’s intuition told him he was “sitting on top of the most important news story in the world”. His subsequent photographic essay documenting the construction of the wall earned him a British Press award and a permanent contract with The Observer. It also signalled the direction of the next and most celebrated stage of his career: conflict.

McCullin speaks of his adventures not with with the self-glorifying bravado you hear from some veteran reporters but a wry, detached tone. Yet he did some extraordinary things, such as talking his way on to a mercenary flight in Congo, only to be imprisoned and then threatened with torture and death at the other end. His compulsive desire to get to the heart of the trouble might have run on adrenaline but it produced images, in the heat of the moment, of astoundingly vivid composition.

Nowadays, McCullin expresses doubts about his war photography – or rather doubts about its purpose and effect. “I don’t deserve what photography has given me,” he says. “I think I’ve been overcelebrated.”

A Somerset landscape from 2004

When I say that the breadth and calibre of his work is certainly worthy of celebration, he says: “It’s worthless to me because it hasn’t changed a thing.”

I can’t work out if this is a genuine conviction or a kind of despairing claim. There is a moral and aesthetic argument to be had about the documentation of suffering, about consent and utility. What is its role? What are the obligations of the documenter? They are questions that are not easily answered, and there are plenty of examples of “war porn” – images of torture and sadism that, as in the obvious case of Islamic State (IS) beheading videos, are intended to dehumanise the subject and desensitise the viewer. But McCullin’s work is not voyeuristic or exploitative because, even in the most dire circumstances, he has always kept his eye on the essential humanity of his subjects.

Conflict prevention seems an impossibly high bar by which to judge photography or any other journalistic or artistic form. The Greeks were writing plays about the horror of battle 2,500 years ago, but no one faults those works for their failure to stop war. If that were the presiding rationale, all efforts to document war would be pointless.

“Yes,” he agrees, “it’s impossible. Before one war is finished, there are two waiting in the wings.”

As fine a photographer of war as McCullin has been, he is also much more than that. His photographs of homelessness in east London in the 1970s are social observation at its most affecting, while his Somerset landscapes are full of a brooding majesty.

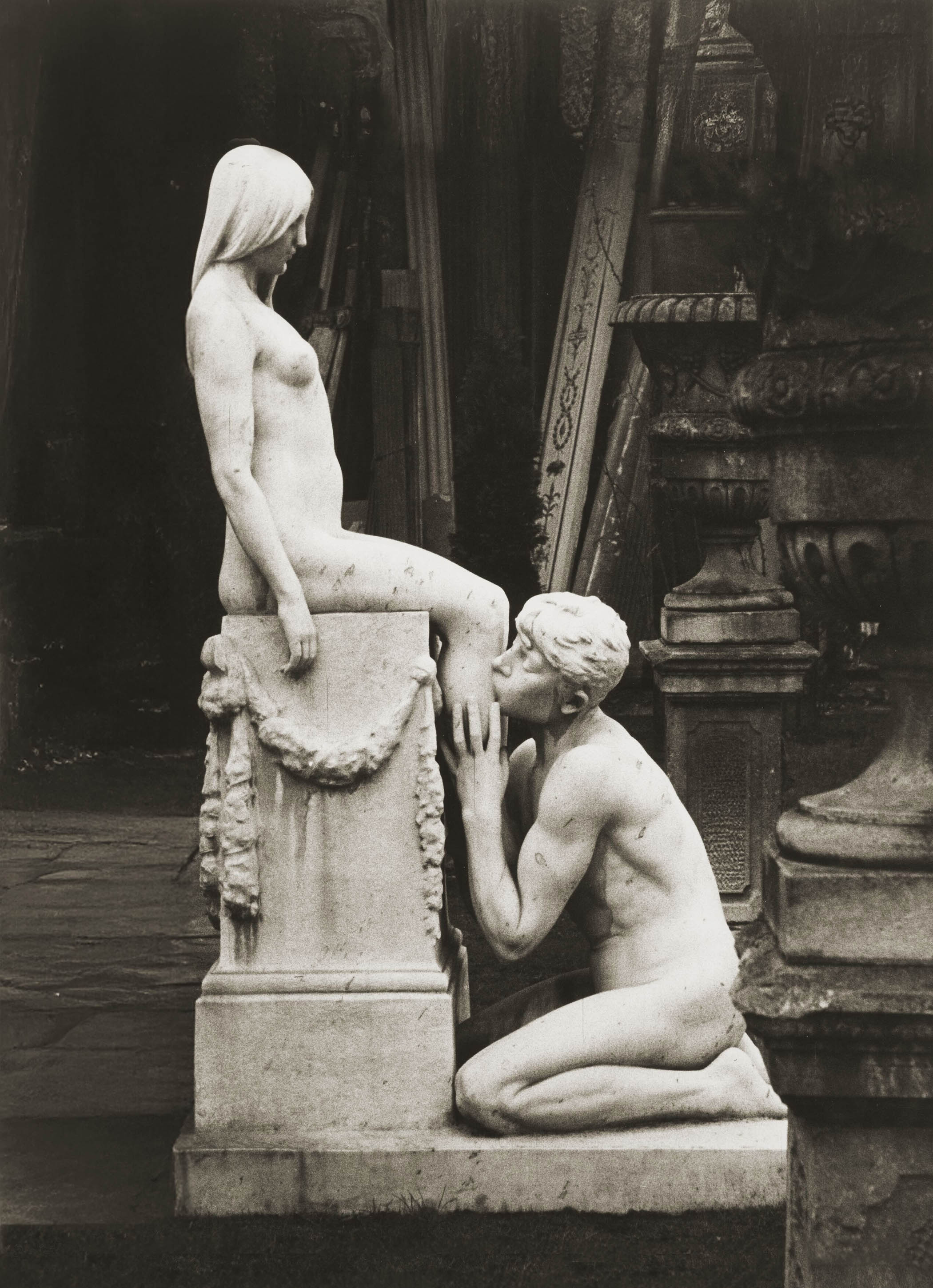

A statue in a reclamation yard in London, from 1963

And for the past 25 years McCullin has also been photographing Roman statuary: gods, warriors, lovers, all blasted by history and somehow preserved for posterity. He started this epic study in Leptis Magna, Libya’s great Roman ruin. Since then, he’s travelled the world, from leading museums to the Syrian city of Palmyra that was overrun just over a decade ago by IS. The exhibition at the Holburne Museum in Bath, entitled Don McCullin: Broken Beauty, is showing a collection of these photographs. If even the trees and clouds of his landscapes are brimful of foreboding, then it’s no surprise that his images of Roman statues, with their missing limbs and chipped faces, form an essay in pain and beauty. “When I stand in front of these great memorials,” he wrote last year in a piece accompanying some of his statue photography, “I think two things. First: ‘My God, that’s amazing.’ Secondly: ‘Hang on – it was at the cost of great suffering.’”

That dichotomy encapsulates McCullin’s vision, which is capable of producing moments of grace in the starkest of circumstances, and of locating the anguish in the most serene of settings. He remains deeply troubled by what he has witnessed, not just its dreadful content, but his own position of power in recording people at their most agonised and defenceless extremes.

Earlier, on the day that we meet, he says, he was looking through his work and came across the photographs he took of dying children in Biafra. I know the ones he means. They are, I think, the most disturbing in his collection: desperate, emaciated children, all bones and distended stomachs, hoping against hope for the tiniest shred of sustenance.

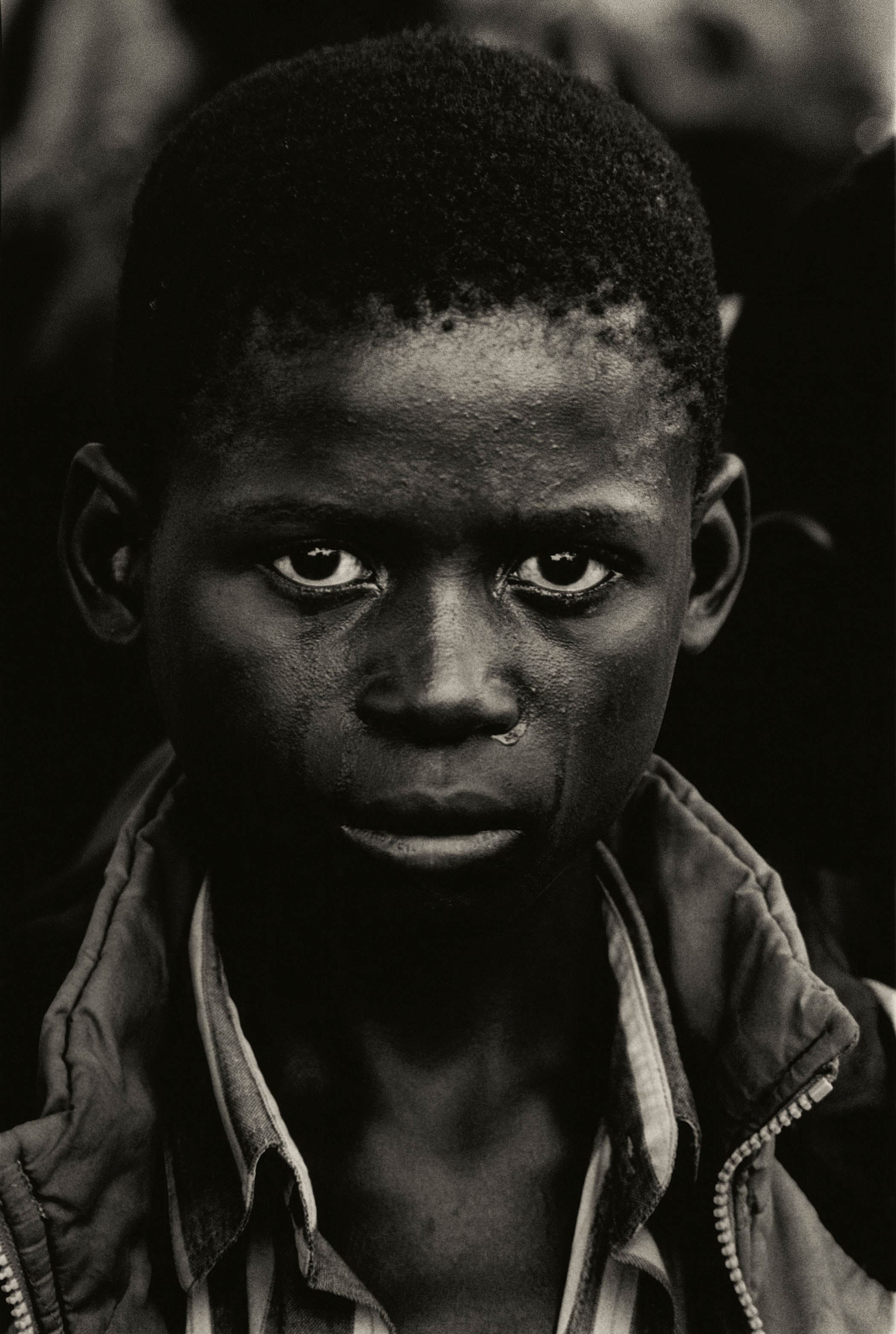

“You knew when you pressed that button that the people in those pictures would not survive,” he says. “That makes you feel incredibly unclean. And then you say: ‘Is there something wrong with me?’ You don’t have the right to steal other people’s images, more so when they’re suffering and dying. I’ve committed some very unpleasant deeds. I’m like a moving train that’s carrying a sackload of shit.”

A Zambian boy crying at the funeral for his father, who died from Aids, in 2000

On the page, his words can look morbid and filled with self-recrimination, but that’s not how McCullin comes across in person. He’s enthused, amused and full of plans – he is flying off to Indonesia the next day with his third wife, the travel writer Catherine Fairweather. Nevertheless, he feels guilty about what he documented, his material wellbeing, and the dereliction of his first wife and their children when he was busy risking his life in far-flung corners of the world.

On one occasion when he was abroad, his eldest son, then a young boy, swallowed a piece of rubber from a toy bow and arrow and it got stuck in his throat. The boy nearly died but was saved by a doctor neighbour who turned him upside down and punched him in the back. “My wife was carrying a huge responsibility, and one of the tragedies of my life is that I separated from her later on and she died on my son’s wedding day,” he says, and for a brief moment his eyes well up. Unlike many other war junkies, McCullin never really buried his stresses in booze, and avoided drugs. He doesn’t think he ever suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, though he has had bouts of depression. The “absurd side” of his life, he says, was the “usual silly male thing of chasing after women”.

He’s been happily married to Fairweather since 2002 and they have an adult son. He speaks proudly of his five children (four sons and one daughter), all of whom appear to have inherited his restless appetite for travel. And he seems to have close relationships with them all. “My [first three] children have forgiven me for leaving my first wife,” he says.

He has lost many of his favourite travel companions down the years; Norman Lewis, Bruce Chatwin – “people who had knowledge and education and were prepared to share with me” – and the king’s brother-in-law, the writer Mark Shand: “I really miss him.”

Fishermen at play on Scarborough beach in 1965

If you stick around long enough, all your peers die. He’s tickled, though, that Tom Stoppard’s widow, Sabrina Guinness, gave him the playwright’s hi-tech hearing aids as a small bequest.

McCullin moved to Bruton 40 years ago, he says, to get away from Notting Hill and “now Notting Hill’s here”, noting how fashionable this part of Somerset has become, with its destination restaurants and a well-heeled London exiles. “It was a very sad place when I first came here,” he says. “After six o’clock at night, you’d be lucky to see another human being.”

Now he is a pillar of the local community. He cherishes his home, adores his wife, has a loving family and widespread professional respect; he still travels; and he was knighted in 2017. He has seen and photographed more horror, danger and turmoil than perhaps anyone else alive, yet he has survived – indeed flourished. He should be the very picture of nonagenarian contentment.

“I have a wonderful life,” he says, “but I feel uncomfortable because I don’t think I deserve this much.”

The young boy who felt he merited more has grown up to feel that he has been rewarded with too much. If the price of survival is guilt, then McCullin has paid his dues. His work requires no apology. It speaks all too eloquently for itself.

Cows on Flooding Meadow in Somerset in 1992

Don McCullin: 90 is at Hauser & Wirth, Somerset, from 14 February to 12 April; Don McCullin: Broken Beauty is at the Holburne Museum, Bath, from 30 January to 4 May. The Stillness of Life, a collection of McCullin’s still lives and landscapes, is published by Gost Books (£80)

Photographs courtesy of Don McCullin and Hauser & Wirth