Whether the Steve Witkoff plan to bring peace to Ukraine through capitulation ever amounts to anything, defence company shares have heard the bell toll. After a very long bull run, the highest hopes of those seeking rearmament are not being fulfilled, while the reality of cash-strapped European governments unable to afford their own rhetoric begins to sink in.

In the UK, the share price of BAE Systems has fallen by about 13% in the past month and Babcock International is down by 8%, while the FTSE 100 Index has seen almost no change. In BAE’s case, 10 percentage points of that fall has come in the past two weeks, since the Witkoff plan has gained some traction. If peace did come to Ukraine, and that’s still a very big if, the suspicion is that western European governments, under budget pressure almost everywhere, might use the moment to slow down their expensive rearmament plans.

Much of the rhetoric on rearmament of the past few years has yet to translate into substantially higher spending. In the budget last Wednesday, the chancellor confirmed the intention to increase defence spending from 2.3% of GDP to 2.5% (2.6% if the intelligence spend is folded in), but this increase does not start to flow until April 2027, still 16 months away. In the current financial year, chatter within the Ministry of Defence says that the finance department is seeking to cut spending by £2bn before April because the plan is unaffordable.

That means that even the committed increase in defence spending in 2027 will be enough only to stop the MoD cancelling programmes; there will not be any new money for the kind of expensive weapons systems service chiefs are desperate to order. Budget increases to 3% or 3.5% of GDP would be needed to trigger significant new orders from defence companies. Even with war raging in Ukraine, those increases remain hopes for the 2030s, despite what the prime minister has said to Nato and President Trump. That kind of money is not in the budget yet, and if there were a settlement between Moscow and Kyiv, the suspicion is that the increase may never happen.

There will not be any new money for the kind of expensive weapons systems service chiefs are desperate to order

There will not be any new money for the kind of expensive weapons systems service chiefs are desperate to order

Defence companies have had an amazing bull run since the war in Ukraine broke out almost four years ago. Over the past five years, BAE’s stock is up by 214% and Babcock’s by 221%, even after the correction of the last month. They have been among the best-performing FTSE 100 shares, the index rising only 48% over the same period. Expectations of growth remain above average too. BAE is trading on a PE ratio of 25 and Babcock 23, compared with the Index’s average of 18.

It’s a similar story in continental Europe, where Rheinmetall has gone from moribund five years ago to a €69bn valuation today, a rise of 1,824%. A large rise in share value has come in the past year since the new chancellor, Friedrich Merz, announced a plan to double defence spending to 3.5% of GDP by 2029 and make the Bundeswehr “the strongest conventional army in Europe”. The money for this will come from a €180bn special fund, designed to circumvent the strict German federal debt limits, but the plan faces opposition, and if peace came to Ukraine, that opposition would likely increase. Rheinmetall’s share price has fallen by almost 15% in the last month.

Similar gaps are evident elsewhere. All of the EU’s Security Action for Europe €150bn loan fund has been requested by member states, but nothing has yet been drawn down, pending the arrival of national plans before the end of 2025. This is part of the larger €800bn ReArm Europe plan presented in March but still being discussed, and is described by Brussels insiders as being “at an early stage”.

Rheinmetall’s share price is sky-high, with a dividend yield of 0.55% and a PE ratio of about 80, but it is underpinned to some degree by Merz’s apparent determination. BAE’s prospects seem much more questionable, given the deep budget bind the British government is in.

Equipment orders already announced, such as Norway’s purchase from BAE of five Type 26 anti-submarine frigates, are likely to proceed under any circumstances, as countries guard against Russian naval threats. But others, such as the plan for the UK to have a fleet of 12 next-generation SSN “hunter-killer” submarines costing about £2bn each, look highly speculative at this point.

It's also questionable whether European arms companies are adapting quickly enough to the changed tactics coming out of the Ukrainian war. They are geared to expensive, bespoke, low-volume products; the future looks more likely to be cheap and cheerful mass production.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

For now, there is plenty of cash flowing through defence companies, and BAE has an order book of more than £77bn, with £27bn of those orders received in 2025. Yet the risks to further increases in spending have gone up, and the market is starting to notice.

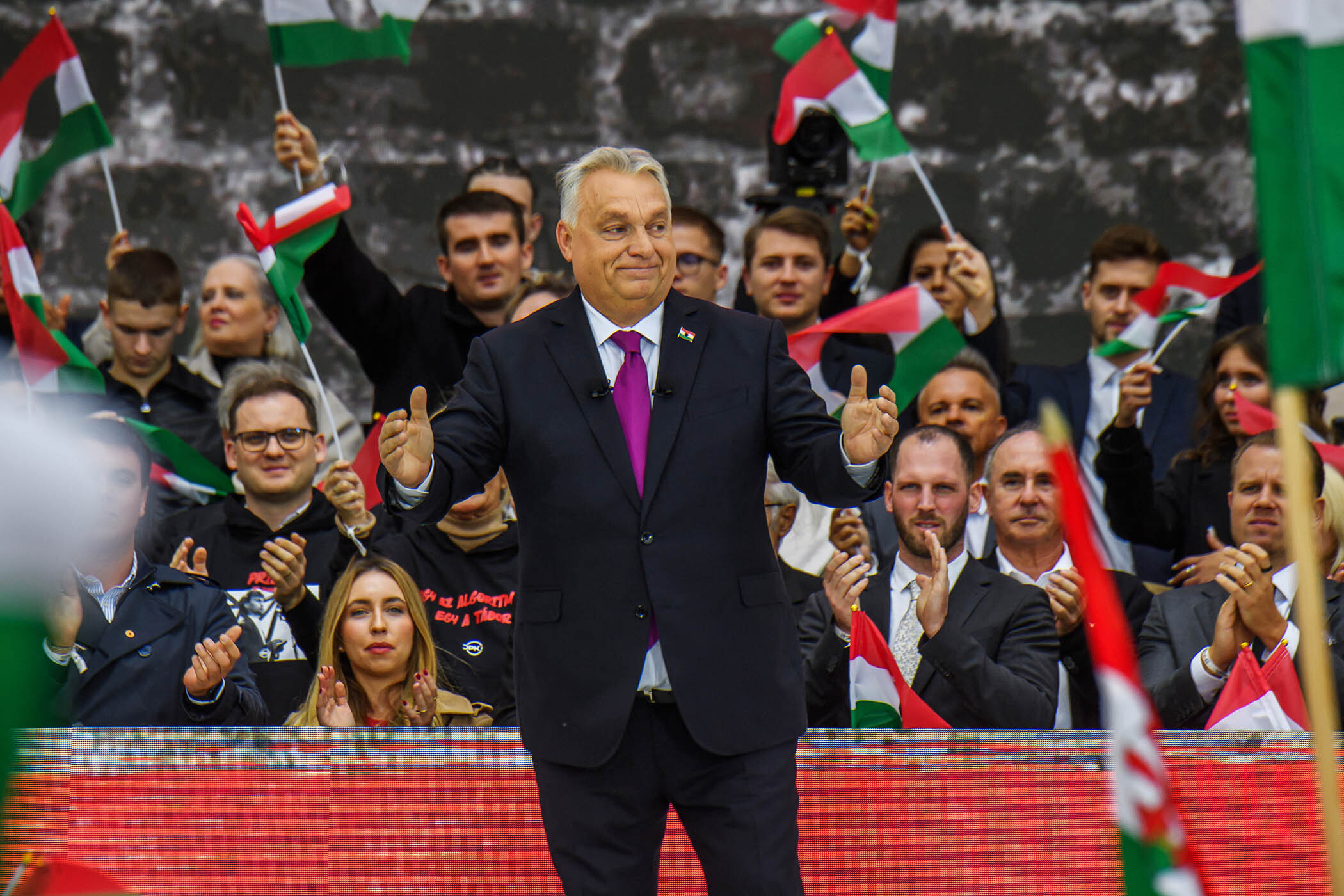

Photograph by Leon Neal/Getty Images