The world’s financial leadership, leavened with a sprinkling of civil society activists, gathered in Washington DC last week for the spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank. Usually, the two sorts of visitors are at odds on the future of the twin institutions. On this occasion there was an anxious unanimity; both shared a similar concern. Were the two organisations next in President Trump’s firing line? Might the US even withdraw from them?

Then, on Wednesday, Scott Bessent, the US treasury secretary, seemed to offer a reprieve. In his first formal comments on the institutions, he said: “Far from stepping back, America First seeks to expand US leadership in international institutions such as the IMF and World Bank.” The relief in the conference rooms and Foggy Bottom bars and cafes was palpable; the instant reaction, we can live with this.

However, as the week went on, doubts returned. Was this White House policy, or just treasury policy? Might the president ultimately decide differently? In the chaotic power process of Trump’s Washington, it is hard to know.

Bessent acknowledged what an extraordinarily good deal these institutions have been, contributing to the prosperous US run since the second world war as leader of an international order based on globalising markets and the rule of law. But critics of the Bretton Woods institutions lurk in Congress and in the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Russell Vought, the OMB director, was one of the authors of Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s unofficial blueprint for a second Trump term. It called for US withdrawal from both the IMF and World Bank.

Moreover, Bessent’s commitment to staying in was linked to a demand that the institutions revert to being reliable instruments of US priorities, including by dropping contested themes such as climate and gender and prioritising the energy sector, including oil and gas and, especially, nuclear. In other words, this will be membership on America First terms.

The two leaders,Ajay Banga at the World Bank and Kristalina Georgieva, his counterpart at the IMF, have carefully walked a thin line. Banga, a former Mastercard CEO, dwelled all week on reliable Republican themes including job creation and giving a bigger role to the private sector. Both avoided public mention of issues that ignite Maga culture wars such as the climate crisis and diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), though their institutions continue to work on both. As they must, if global development is to remain on course and in order to meet the expectations of most of the other 190-odd member states, which were chafing at outsized American influence over the two institutions years before Bessent’s move to increase it further.

Yet there were moments when they dared to speak some truth to power. While ducking direct criticism of Trump, Georgieva in her curtain-raiser press conference was unambiguous that the tariff wars are knocking growth seriously off course. Having grown up as a dissident in a despotic communist Bulgaria, she learned early in life how to navigate such sensitivities. Her chief economist then was drawn into the controversy around Trump’s attacks on Jerome Powell, the chair of the US Federal Reserve, saying central bankers’ independence must be respected by politicians.

Bessent is right to see value in the Bank and IMF. At almost no cost to the American taxpayer, over the years hundreds of billions of dollars have flown from both institutions, leveraged through market borrowings and issuance of credits, to firefight financial crises and fund global development. Indeed, the IMF has just concluded its 23rd rescue package of $20bn for Argentina, now led by a Trump favourite, the chainsaw-wielding President Milei. And it is the borrowers, not the US and other western donors, whose interest payments primarily pay for the running costs of both organisations.

‘Few at the meetings want the US to leave, but many talk of the need to draw red lines to keep Bessent and his boss in check’

‘Few at the meetings want the US to leave, but many talk of the need to draw red lines to keep Bessent and his boss in check’

Bessent has been brave in backing the two institutions given that foreign aid is a cultural lightning rod for Trump’s Maga base. Although it accounted for less than 1% of federal government spending, Elon Musk’s first target at the “department of government efficiency” (Doge) was USAID, America’s own bilateral aid agency. Doge has noisily shut lifesaving programmes around the world, literally overnight in many cases, at a potentially huge cost to lives.

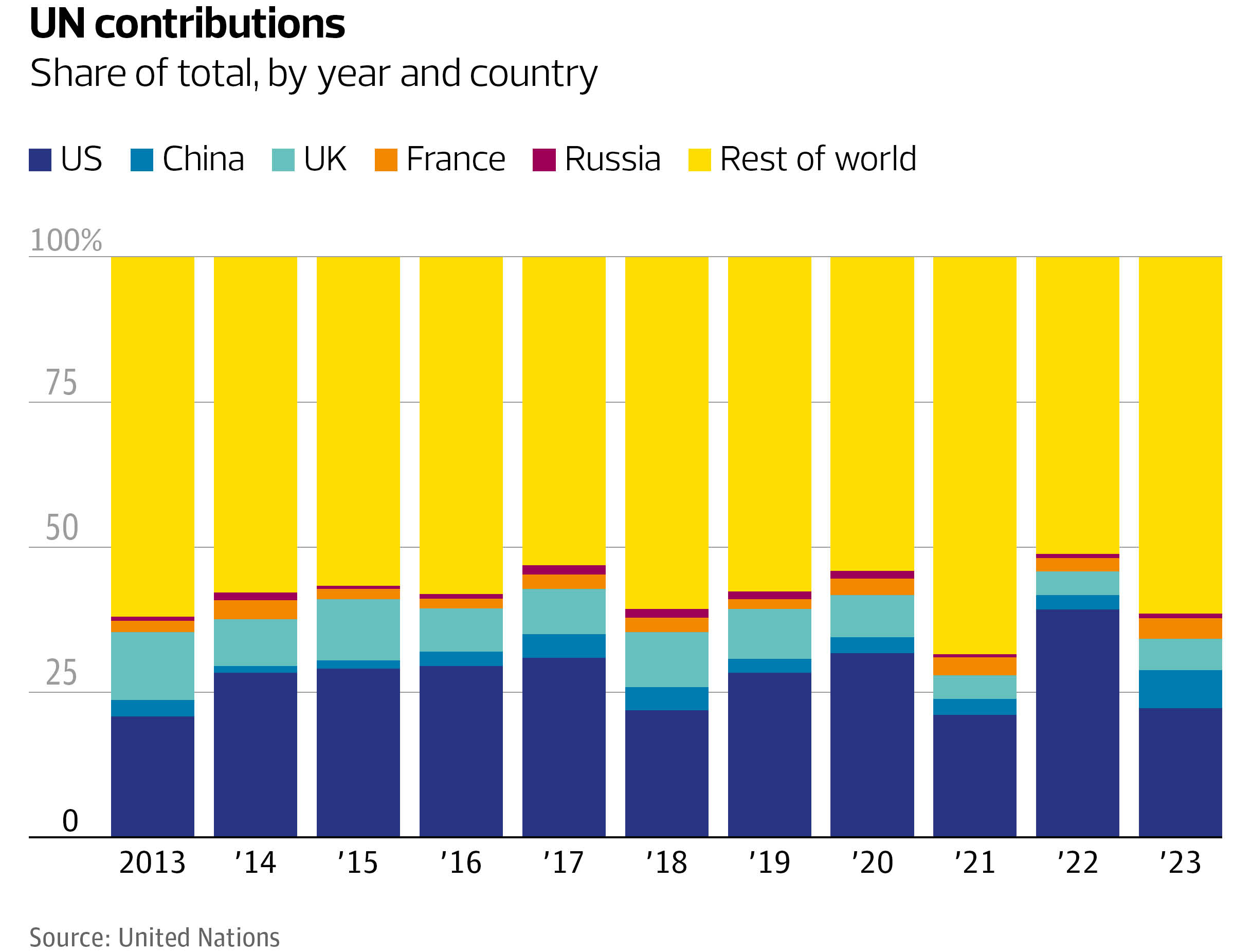

The administration has now turned its sights on the UN and the contributions the US makes as the biggest donor. A leaked draft memo leaked proposed zeroing out nearly all these contributions, including funding peacekeeping operations. More limited cuts by the first Trump administration led, as observers noted, to China filling the vacuum and extending its influence in the UN and soft power on the ground.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In Europe and the UK, too, aid has fallen off a cliff. It is now back to levels last seen in the early 1990s. The public collapse of support for aid flies in the face of results. A 20-year surge in aid and development spending after 1989, a post cold war peace dividend of sorts, contributed to the most rapid rises in life expectancy, literacy rates, and health outcomes in history. Poverty as a proportion of the global population was more than halved.

If Bessent is serious about driving an America First approach that makes the Bank and Fund exclusively advance US priorities at the expense of the rest of their membership, that may in its own way be as big a threat to progress as American withdrawal would have been. Prioritising fossil fuel development over renewables could be just the beginning. With no bilateral aid programme of any size left, Trump might instead force his Washington neighbours to fund his global ambitions, from Gaza to Panama.

Few gathered for the meetings want the US to leave the IMF or the Bank, after eight decades of mostly productive partnership. But many of them talked up the need for both to draw some red lines to keep Bessent and his boss in check. The legitimacy of both institutions in a politically divided world requires them to serve all their borrowers’ agendas and needs, not to kowtow to one over-mighty founder.

Lord Malloch-Brown is the former deputy secretary general of the UN

Photograph Jose Luis Magana / AP