The decision on whether to leave her post early may define Christine Lagarde’s legacy, but there is no denying she has “accomplished a lot” as president of the European Central Bank (ECB), as she told the Wall Street Journal this week.

Lagarde’s “baseline” is to finish her term, which ends in October 2027, she says. That has not stopped speculation that she will step down sooner, whipped up by an article in the Financial Times last week.

Populist candidates of the right and left – many opposed to current mainstream central bank thinking – look likely to win next spring’s French presidential election.

If Lagarde quits her ECB role before then, that would allow current French president Emmanuel Macron to work with German chancellor Friedrich Merz to put in place a proven “safe pair of hands” central banker with an eight-year term, strengthening the bank’s independence from day-to-day political pressures.

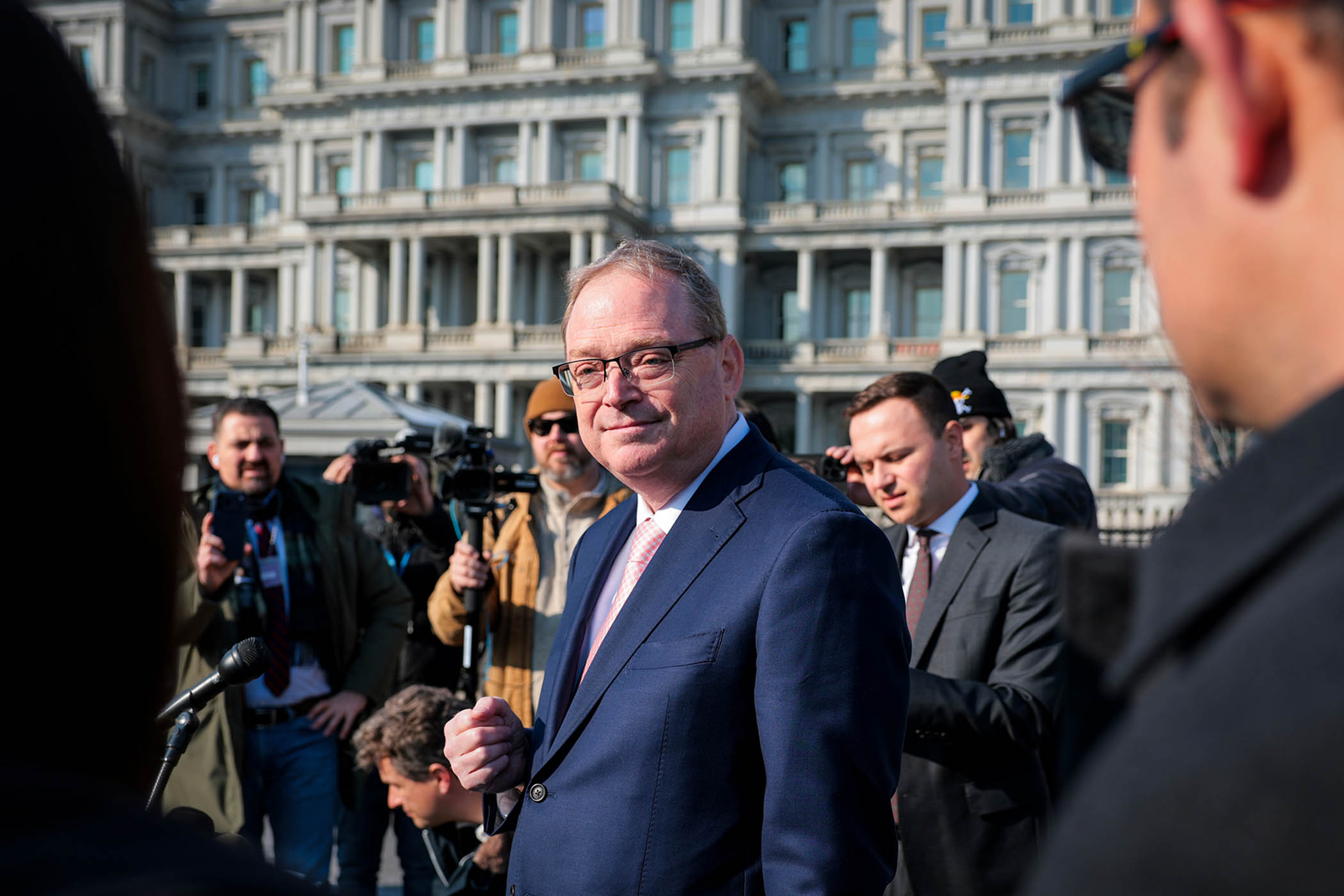

Donald Trump’s attack on the independence of the Federal Reserve has shaken confidence in the future of the institution that will not return until incoming chair Kevin Warsh shows he has the spine to go against the president’s wishes on interest-rate policy. Given Europe’s myriad economic problems, no one should want a similar fate at the ECB.

Lagarde may feel that seeing out her term avoids what would be a clearly political act, quitting to deprive a potentially extremist French president of a choice they, by right, should help make. The bigger risk is that by staying too long she becomes a sort of central bank version of American supreme court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was revered for how she did her job, but by staying too long helped hand over her beloved institution to her enemies.

Photograph: Frederick Florin/AFP via Getty

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy