You can listen to Eva Wiseman’s story on this week’s episode of The Slow Newscast, The Match: My Sister and her new DNA, here.

What was she going to cook? That was the question last week in my family WhatsApp group. What do you make for the person who’s saved your daughter’s life? My mum – having largely returned to a kind of lockdown while my sister was immunocompromised owing to chemotherapy and then six rounds of total-body irradiation – has returned to her social life with cautious vigour, a serious cook and perfect host. My sister emailed her stem-cell donor (an act that still feels mad and miraculous) and asked what his family liked to eat. He replied: hot dogs?

She was very cool about her hair falling out. Weirdly cool. She didn’t fancy wearing a wig, and only sometimes wore a hat – in her wedding photos she is dramatically, festively bald. I found the hair loss more difficult than my sister did. It was hard to hold in my head the fact that it was a response to the treatment rather than an illness in itself. She’d always had long, luxurious straight hair. At first, seeing her white scalp felt wrong – inappropriate, something that should surely be covered, like an open wound.

I got used to it. Or at least, over time it scared me less. But part of why her baldness felt so shocking was that it was really the only external sign my sister was ill. She got thin, of course, very thin; and when the little meals my mum had made would remain uneaten, our eyes would meet, flickeringly, over the table. But even in hospital, stuck with needles, she remained positive, sometimes merry, as she waited to see if a stem-cell donor might emerge. It seemed, to me, increasingly unlikely.

Matching blood stem-cell donors to patients relies on genes called human leukocyte antigens. HLAs are proteins the immune system uses to distinguish between the body’s own cells and invaders, such as viruses. “Self” or “non-self”, they call them. I like the poetry of this. It’s the first time I’ve allowed myself to Google some of this stuff, after years of keeping such websites sharply at arm’s length. From this distance, the words are sometimes beautiful. A match of at least eight DNA markers is needed to prevent the donor cells from attacking the patient’s body, but there are millions of possible combinations. HLAs are inherited from biological parents; having learned, soon after my sister’s diagnosis, that I wasn’t a match, the idea that some stranger might have more DNA in common seemed, though I didn’t say it out loud, improbable. Which is partly why, when news of a 10-out-of-12 match arrived, it felt like such magic.

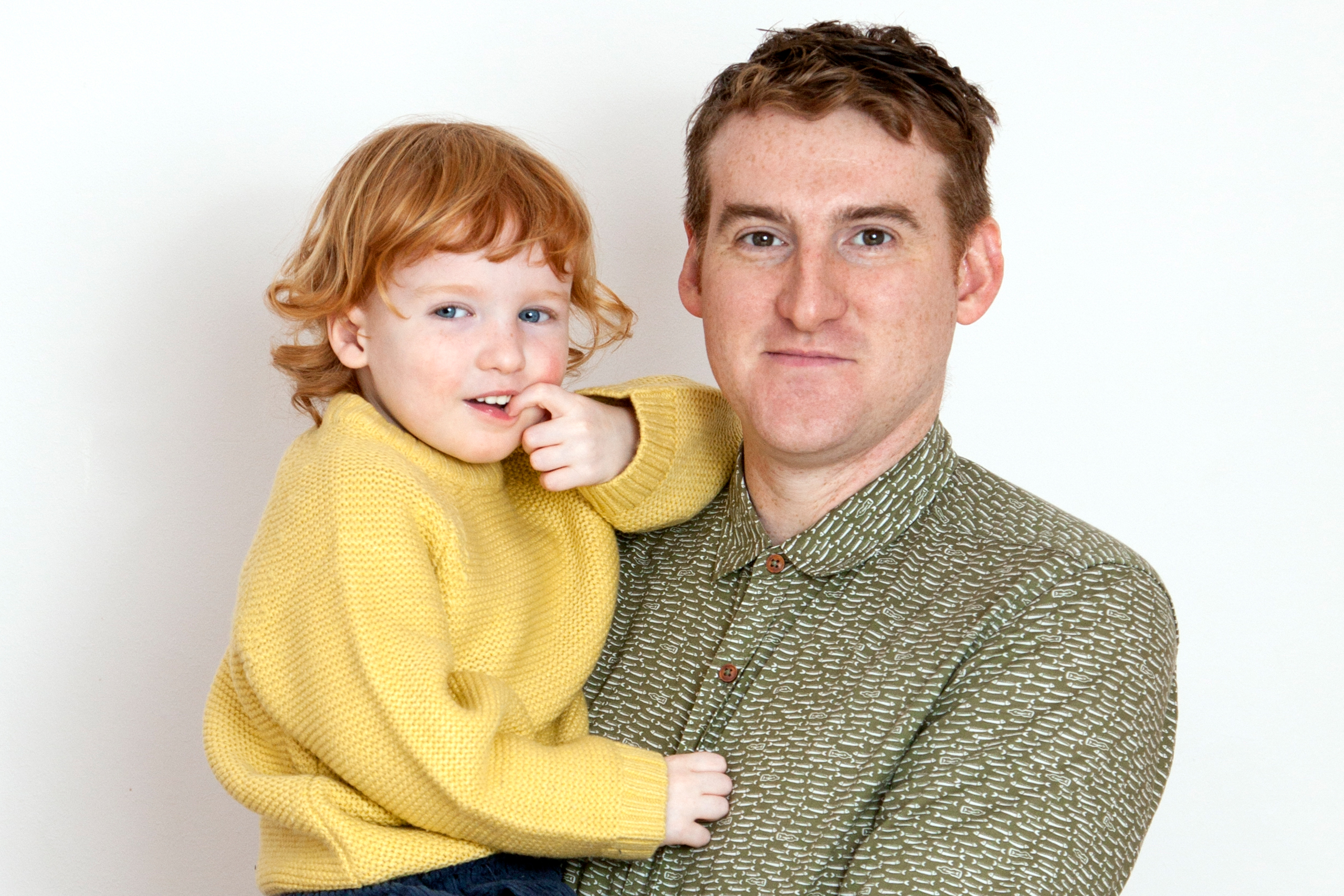

After the transplant, various mean things happened to my sister’s body. Her eyes were painfully dry, her feet difficult to walk on; her fingertips tingled. On a trip to her inlaws’ caravan, she went mysteriously, briefly, blind. She was on alert for signs her immune system was rejecting the new cells – a concept that proved, I think quite conclusively, the dualism of mind and body. But time passed. Her daughter started school; her son, who had only really known her in treatment, started to talk; and her hair grew back. Except now it grew in very tight brown curls. In an appointment with the consultant, my mum asked why this was. He had started a research project to discover why some people’s hair grows back differently after transplant – whether it’s purely the chemo or whether it could be related to the donor’s DNA – but he couldn’t get funding because it didn’t directly impact health. We talked sometimes about this mystery donor; we wondered, idly, about his hair.

There are a handful of time periods that become important after a transplant. The first is six months. My sister’s doctor told her 75% of people with acute myeloid leukemia who relapse do so in the first six months after transplant. Then the threat of relapse drops after a year, and again after two years. At each point we released a little more breath, a low whistle. After five she will be able to say, “I had leukemia”, past tense. As two years came around, the charity Anthony Nolan forwarded the donor’s email address to my sister; five months later, Bret came with his family to my parents’ for lunch.

At 1pm, my sister and I stood nervously by the kitchen window, watching the road. There was something obscurely romantic about the situation – a little like a first date, yes, but more like a wedding, or adult birth.

Related articles:

And then they were here, and we sat outside, on one of the last sunny days. And all our kids ran off to play, and my dad poured drinks. We gathered around Bret shyly, grinning. We got him to tell the story of his donation again and again, like a bedtime story, knowing they had to leave at three. But three passed, and then four, then six, and it became clear that their hard out had been a precautionary myth in case it was awkward, or we were awful. It felt like welcoming in a long-lost arm of our family, he seemed instantly familiar – his hair, tight brown curls.

They left as night approached, with plans to meet again. They’ll stay in the attic room my parents redecorated for my sister’s convalescence, or decline. My mum’s extensive menu included hot dogs and then a salad of burrata and nectarines, gently grilled. We didn’t notice what we were eating, in the end, but we ate it all.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Want more of this story?

Listen to our new episode of the Slow Newscast:

And another thing… Space oddities, offbeat artworks and the power of love

Lipstick traces The David Bowie Centre has just opened at V&A East Storehouse in London, and I’m looking forward to taking my daughter, whose Bowie poster sits squarely between pictures of Chappell Roan and Taylor Swift. At the V&A’s Bowie exhibition in 2013 I remember looking mournfully at the pieces of paper ephemera – song lyrics, letters, a tissue covered in his lipstick – and realising that his was the last generation in which such treasures would exist.

Schlock of the new The Deadly Prey Gallery, in Chicago, works with Ghanaian artists to produce dazzling, sometime bizarre, hand-painted movie posters. I have my (cinephile) eye on prints of Blue Velvet, Cry-Baby, and Death Becomes Her.

From the heart Ella Risbridger is such a wise and funny writer (her cookbook/memoir, The Year of Miracles, is exquisite on cake and grief) that I pre-ordered In Love With Love, an ode to romantic fiction from Jane Austen to Jilly Cooper. “Why do we read?” she asks. “How do we love when the world is falling apart? And what does it mean that love is the one subject of which we never seem to tire?”

Photograph: Getty images