Peter Mandelson deserves all that is coming to him. So do those, both inside and outside the Labour party, who for decades have supported him, eased his path to power and wealth, used him to take out political opponents, and helped him demean national politics.

The significance of the Mandelson affair lies, though, not simply in his alleged criminality, his betrayal of friends and colleagues, or even in his relationship with the convicted paedophile and sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein, but also in what that relationship tells us about the character of the contemporary elite. The Epstein files – the huge cache of emails between Epstein and his circle, part of which helped bring Mandelson down – provide a glimpse of how power operates in the shadows, beyond the reach of democratic control.

Two themes leap out from the Epstein emails: the depth of misogyny and the coveting of information. “Cunt”, “bitch” and “pussy” pervade the conversations. Epstein describes one unnamed woman as a “wrinkly old hag, just because she is ri=h [sic] she thinks she can talk down to everyone…bags of cottage cheese in her pants... bitter old jew”. Acquiring “pussy” is a constant obsession. “Meet me at class 9:30… Promise an abundant [sic] of young pussy flesh,” one unnamed correspondent emailed Epstein. Some exchanges hint at a much darker story. “Thank you for a fun night,” someone whose name has been redacted told Epstein. “Your littlest girl was a little naughty.” These were private messages, never intended for public view. Nevertheless, they reveal how the “Epstein class” behaves when it thinks no one is watching.

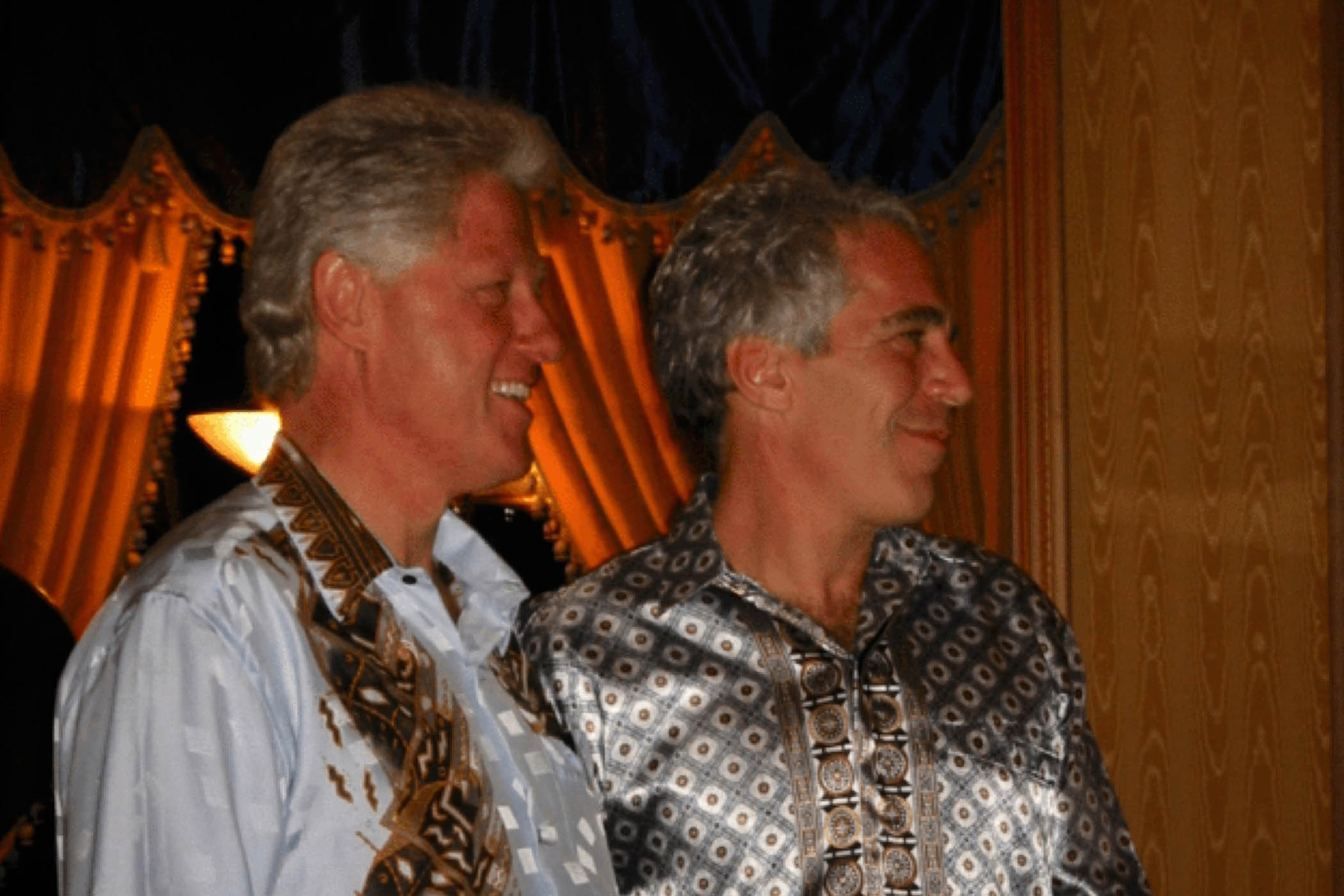

Beyond the misogyny and moral squalor, the files also provide a portrait of how power works to sustain itself. Epstein, who made his fortune as a financier, was not merely a sexual predator but the creator of a vast web of influence that became a node in geopolitics: a network that brought together the wealthy, the powerful and the seemingly smart – politicians and businessmen, tech bros and filmmakers, scientists and academics. Within Epstein’s orbit lurked Donald Trump and the Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, Bill Clinton and Ehud Barak, Peter Thiel and Richard Branson, Woody Allen and Elon Musk. Even Noam Chomsky was there, a thinker who has spent a lifetime cultivating his anti-establishment credentials, but who also advised Epstein on how to deal with “the hysteria that has developed about abuse of women”.

Sex and rape may have been a fixation for many within Epstein’s network, but they were also, in their minds, the froth; a chance for some depravity away from public scrutiny, while pursuing their power-seeking and money-making projects.

Sex and rape may have been a fixation, but also, in their minds, the froth

Sex and rape may have been a fixation, but also, in their minds, the froth

What greased Epstein’s network was information. Sometimes it was just gossip. “Saw Matt C with DJT at golf tournament I know why he was there,” former Trump executive Nicholas Ribis coyly emailed Epstein. And then there was the kind of information that Mandelson provided: high-value knowledge that gave those who possessed it an edge, whether in dealing with governments, corporations or crooks. Epstein, the spider at the centre of the web, exploited all that information, sometimes acting as matchmaker, bringing together people whom he thought had common interests, sometimes providing confidants with knowledge that might prove profitable, and all the time enhancing his own power and influence.

Liberal democracies usually attempt to maintain a certain distance between government and profit-making, or at least to present the appearance of integrity. There are registers of interests, the placing of shares in blind trusts while in office, and so on. Yet the “revolving door” between government and business, and the value of the knowledge and contacts that political leaders possess, is central to the operations of power. It is why George Osborne, after leaving office, became advisor to the investment firm BlackRock and is now a managing director of the US tech pioneer OpenAI. It is why Tony Blair has, at various times, been advisor to JP Morgan, Zurich Insurance Group, PetroSaudi, and the Kuwaiti and Kazakhstani governments.

Mandelson short-circuited that process, seemingly acting as a lobbyist while still in government. Many put it down to his obsession with wealth and power and his amoral politics. But these are far from being uniquely Mandelsonian traits. He was merely one actor in a carefully curated web.

A loathing for the liberal elite is an overpowering feature of contemporary politics, much of which is framed around a populist challenge to a predatory elite. The Epstein revelations will only deepen that loathing and provide more sustenance for the populist right. Mandelson’s disgrace and Keir Starmer’s spinelessness will undoubtedly enhance the chances of Reform UK in the upcoming Gorton and Denton byelection.

What the Epstein files expose, though, is how the “anti-elites” are themselves very much part of the elite. Epstein’s network included key figures from the Maga movement: Trump, Thiel, Musk, Steve Bannon and many others. Despite being contemptuous of Trump, Epstein was open to the ideas of rightwing populism. In an exchange with Thiel, he welcomed Brexit as marking a “return to tribalism. counter to globalization. amazing new alliances”, and the possibilities, too, of opening up new ways for enrichment, because “finding things on their way to collapse, was much easier than finding the next bargain”.

Whether labelled “liberal” or “populist”, “globalist” or “nationalist”, every faction of the elite is indicted by the Epstein files.

Photograph by: U.S. Department of Justice/AFP

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy