Last month, Tucker Carlson, former Fox News presenter and now working independently, invited Nick Fuentes, a neo-Nazi provocateur and Holocaust denier, on to his show for a soft-soap interview.The platforming of Fuentes generated considerable criticism within US rightwing circles. In response, Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation, one of America’s most influential conservative thinktanks, came out swinging in defence of Carlson, dismissing the critics as “venomous”.

An even fiercer row erupted, with several members of the foundation’s antisemitism taskforce resigning, followed by a number of academics. Roberts was forced to apologise.

The controversy highlighted an ongoing civil war within America’s Maga movement, between those who see themselves as mainstream conservatives, following in Ronald Reagan’s footsteps, and those they label the “woke right”, hostile to liberalism and globalism, and supportive of white identity politics.

Critics of the woke right accuse it of aping the left. “Like its antithesis on the left,” the liberal writer Thomas Chatterton Williams observed earlier this year, “the woke right places identity grievance, ethnic consciousness, and tribal striving at the centre of its behaviour and thought”. James Lindsay, one of the most influential “anti-woke” warriors in America, claims it can be “more accurately understood as revolutionary progressives in conservatives’ clothing.” Many also worry about the conflict crossing over to this side of the Atlantic. “What starts there always comes here,” Times columnist Danny Finkelstein warned last week.

The phenomenon that Chatterton Williams, Lindsay and Finkelstein worry about is real. On both sides of the Atlantic, we have seen the growth of more overt racism, white identity politics, hostility to migrants, and the growth of both antisemitism and anti-Muslim bigotry. To label this as “woke right”, however, and to view it as a mirror of the “woke left”, is to misunderstand the shift and to allow mainstream conservatism to evade responsibility for helping nurture it. Nor are these ideas being imported into Britain from America. They are homegrown and already here.

Today’s conflict between the mainstream and the “woke right” is the latest instantiation of a longstanding tension within conservatism. Conservatives,observed Roger Scruton, perhaps the most important conservative philosopher of recent decades, believe both in the importance of the free market, private property and individual choice, and in the overriding significance of community, tradition and place as setting limits to people’s freedom. Drawing on Edmund Burke, the founder of modern conservatism, Scruton insisted that the ideal society is built not on liberty or equality but obedience, “the prime virtue of political beings”. The “price of a community” for Scruton, as for Burke, was “intolerance, exclusion, and a sense that life’s meaning depends upon obedience”. Illiberalism was baked into conservatism from the beginning.

So was what we now call identitarianism. Most people think of identity politics as a recent phenomenon, and one associated with the left. Its real origins lie on the reactionary right and its primary expression, long before it was called “identity politics”, was in the concept of race: the belief that your being – your identity – determined your values and place in the world.

Nineteenth-century conservative critics of the universalist ideas that had emerged from the Enlightenment stressed instead particular group identities. “There is no such thing as Man,” the French reactionary thinker Joseph de Maistre wrote in his polemic against the concept of the Rights of Man. “I have seen Frenchmen, Italians and Russians… As for Man, I have never come across him anywhere.”

Such particularism gave rise to the Romantic view of every culture as distinct and separate and of every people as defined by a unique cultural inheritance reaching across the vagaries of history. It also helped nurture the biological concept of race, which came to dominate the understanding of human differences.

Then came Nazism and the Holocaust, in the shadow of which biological ideas of race became more marginalised. Instead, culture became the principal language through which to understand differences between human groups. Paradoxically, in the postwar world, both liberals and the far right appropriated the Romantic vision of culture.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“The true wealth of the world is first and foremost the diversity of its cultures and peoples.”This might read like a liberal advocating for multiculturalism. It is in fact from the pen of Alain de Benoist, the founder of the Nouvelle Droite in France, and one of the most important figures helping remake far-right ideas for the post-Holocaust world.

For liberals and the left, cultural pluralism was an argument for a more inclusive world. For the far right, it provided a vehicle for exclusion and intolerance, and for rebranding racism as white identity. Immigrants, de Benoist insisted, must always remain outsiders because they are carriers of distinct, incompatible cultures and histories. They must be debarred from citizenship, as to be a citizen is to “belong… to a homeland and a past”.

What the “woke right” represents are these kinds of ideas travelling from the far-right fringes into mainstream debates. They have been able to make that journey because politicians and commentators have in recent years looted the far-right ideological arsenal. Many now routinely describe immigrants as “invaders”, question whether black or Asian people can truly be British, lament white people losing their “homeland” and Britons “surrendering their territory” – language that would have seemed almost unthinkable in the mainstream two decades ago.

This is not a case of the right mirroring the left but of old reactionary forms of conservatism reasserting themselves as more liberal strands corrode. Before we can challenge such reactionary ideas, we first have to recognise them for what they really are.

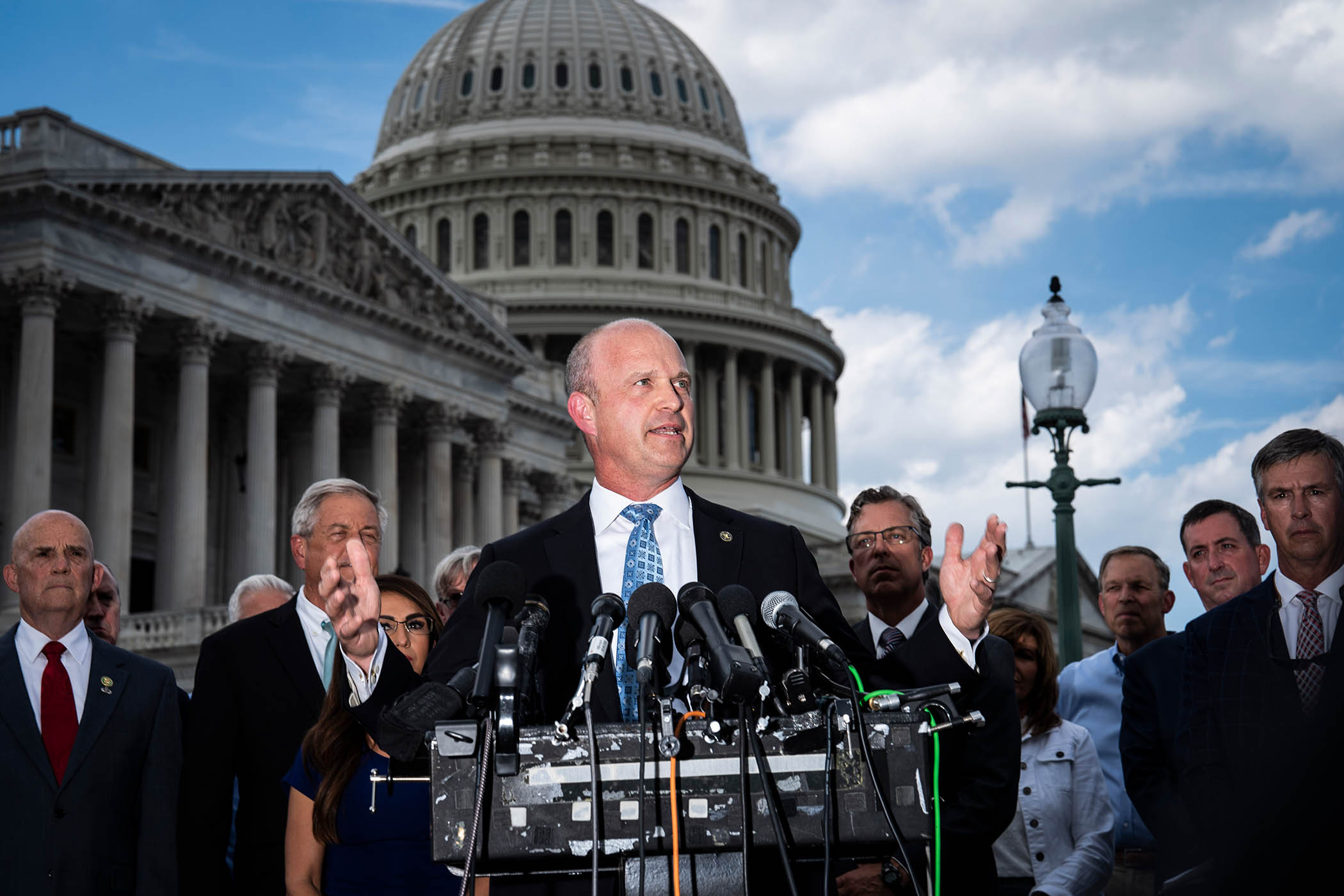

Photography by Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via Getty Images