Illustration by David Foldvari

For live music, it is the age of “dynamic pricing”, a capitalist fever dream so egregious that Gordon Gekko might have looked at it and gone, “Oof. That’s a bit strong.” The theory is that, like airlines and hotels, you sell concert tickets according to demand, charging people as much as they are willing to pay and allowing the market to dictate terms. In reality, it means music fans winding up in Soviet-era sized digital breadlines for so long that they begin giving their children their credit card details and instructing them on how to take their place in the line when they die. And then, when, or if, they finally get to the front, they are often – digitally – held down and viciously bully-rammed into paying many times what the ticket would have cost when they began queueing two days ago.

One is reminded of the gangs in the wild west, bygone age of Glastonbury, the ones who would charge you 20 quid to crawl through their tunnel to the site, where, upon emerging blinking into the sunlight, another member of the gang would unceremoniously mug you. And so it goes nowadays for the Oasis fan, the Radiohead fan, the Ed Sheeran fan. And yet, like Travis Bickle, here is a band that would not take it any more. A band that stood up against the scum and the filth. Here is… Everything But the Girl.

A quick refresher, in case you’re unaware. Everything But the Girl are a big act. The husband-and-wife duo of Tracey Thorn and Ben Watt shifted almost two million records in the old days of physical sales. In the digital era, they have millions of monthly listeners on Spotify. And, like Oasis, they did the one thing that ensures you are a hot ticket – they went away for a very, very long time, after Thorn decided she didn’t enjoy singing live any more. Upon their return to the stage last year, after a decades-long sabbatical that had begun to look more like retirement proper, they could have comfortably sold out the Albert Hall or Hammersmith Apollo and charged pretty much what they liked. They went with a residency at the Moth Club, a 300-capacity working men’s club in east London. No crazy ticket prices either. Somewhere you could hear an agent screaming as a table struggled to bear the weight of the money being left on it.

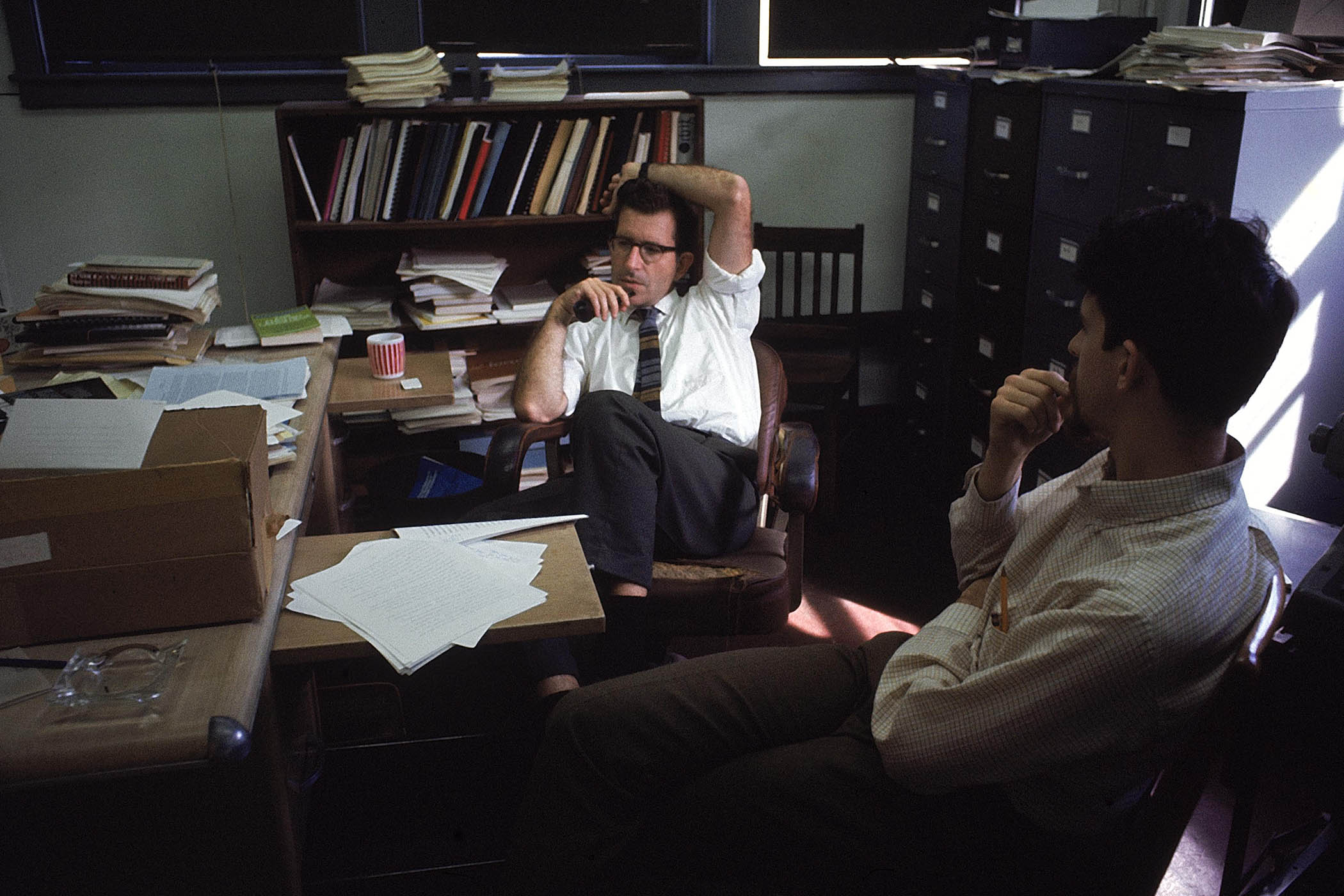

Like the ticket pricing, the Moth (the name is an acronym for South Africa’s Memorable Order of Tin Hats: a network of clubs for former servicemen) is something from a bygone age – a time of cheap wood panelling, Formica, dartboards and ancient carpeting, repaired here and there with duct tape. There are places like it in every city in Britain, tiny pockets of The Way We Used to Live. Retired soldiers drinking pints wasn’t quite enough to keep the lights on and so, for more than a decade, the Moth has quietly become one of London’s best music venues. Everything But the Girl began their on-off residency there last year and have continued it into 2026: onstage there is just Thorn and Watt, their bass player Rex Horan, and their 24-year-old son Blake, from Family Stereo, on additional guitar and vocals.

You sense everyone knows how lucky they are… listening to the fragile songs in this tiny venue

You sense everyone knows how lucky they are… listening to the fragile songs in this tiny venue

Songs from a career spanning five decades are presented in a stripped-down, careworn style that, from the moment Thorn opens her mouth to sing Night and Day, slips a hand around your ventricles, squeezes and doesn’t let go. She breaks into a grin that seems to be saying to herself “why on Earth did I stop doing this for 25 years. Each member of the family takes a turn in the spotlight. Sometimes Blake stands, hands clasped across his guitar, head bowed, listening to his parents sing songs they wrote when they first became lovers, long before the boy onstage tonight was so much as a stray thought en route to the milkman’s eye. The pan-generational element lends extra poignancy to already potent moments, as when Watt senior sings, “there’s still so much I want to do”, on Winter’s Eve, a song about ageing, originally written for his father. Now in his sixties himself, and having survived years dogged by ill health, it is difficult to convey the yearning he fuses into the line. And what a thing it must be for his own son to hear it. It is a moment that would melt the heart of a hedge fund manager.

The audience is utterly rapt. Sitting in the glow of the lager taps, you could hear a pin being picked up. And you sense everyone present knows how lucky they are to be here in this battered little room, watching musicians doing it simply for the love of the game. Listening to these fragile songs in this tiny venue, I was oddly reminded of an experience at the other end of the live music spectrum: 70,000 Oasis fans in Edinburgh’s Murrayfield stadium last year, singing every single word of every single song for two hours straight.

While ostensibly poles apart, both moments were imbued with a sense of the same thing, the thing it is all too easy to lose sight of as you stand there in the Pepsi-Max-Bud-Light-Mastercard-Microsoft-American-Airlines Arena, your 12 quid pint of cooking lager in one hand, your basket of 10 quid popcorn shrimp in the other and your 50 quid tour T-shirt wrapped around your neck. It is the thing live music is supposed to be about, the thing you don’t get from records or streaming, the thing you only get when your heart swells and rises in time with all the other hearts in the room. A sense of community.

Related articles:

And, with yawning inevitability, the Moth Club is now under siege by those with scant notion of community, those of the un-meltable heart, those who would bulldoze it to the ground without blinking to make way for that tawdriest of all things: a “luxury development of stunning two-and-three-bedroom apartments”.

Much later that night, on the way home on the Westway, thoughts of community were much on my mind as I passed the tower block of council flats where Joe Strummer and Mick Jones wrote London’s Burning, and as I passed the sad, black shadow of Grenfell. As I turned the concert over in my head, looking for a way to sum it up, it wasn’t one of the voices from the stage that kept coming back to me. It was Gene Wilder’s as Willy Wonka, his voice hushed and breaking as he paraphrases Portia in The Merchant of Venice… “So shines a good deed in a weary world.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy