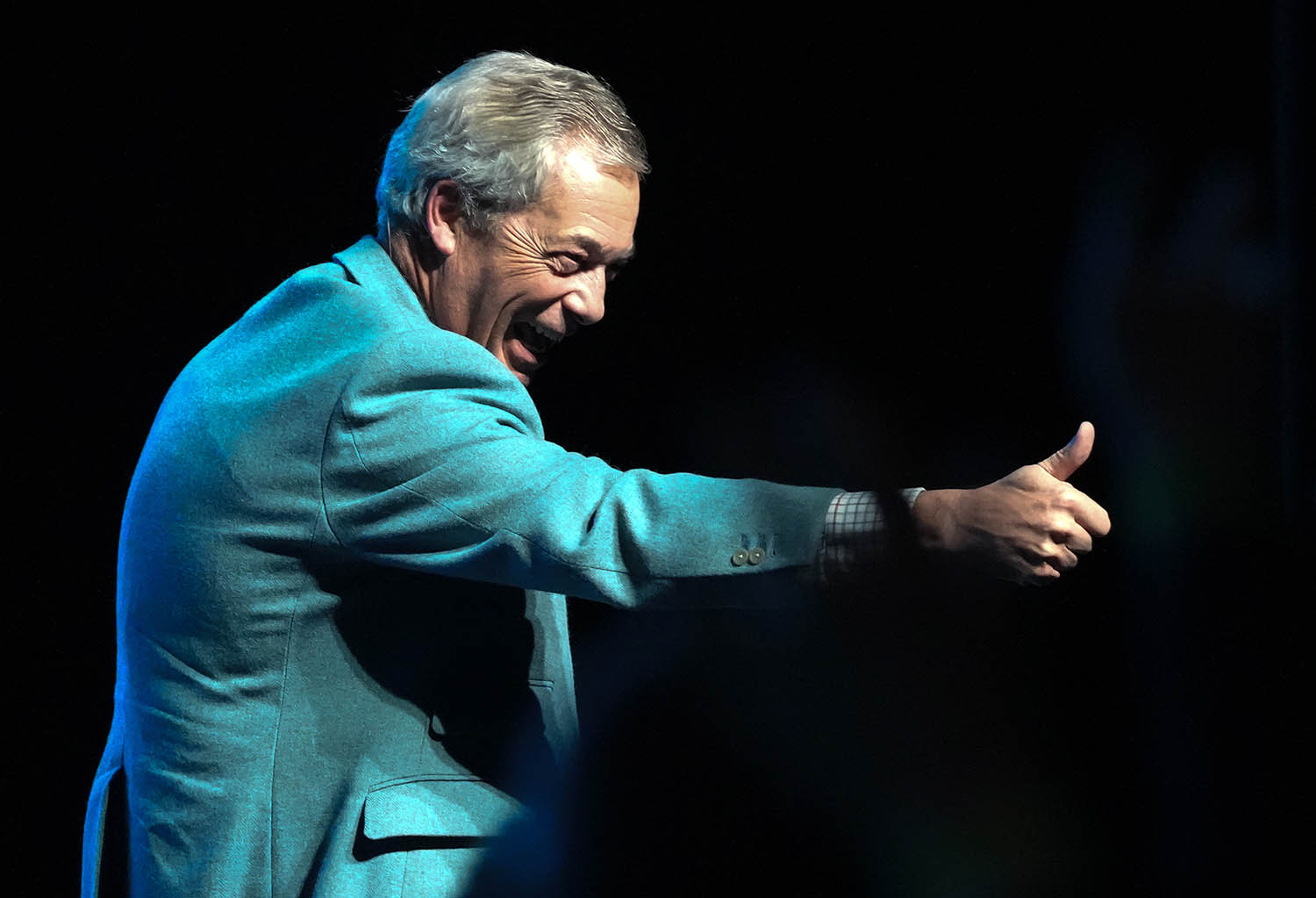

As one of our prime ministers once said in a different context: the kaleidoscope has been shaken. The pieces are in flux. The political landscape, its colour scheme previously dominated by blue and red, now looks like a psychedelic abstract in the style of Jackson Pollock. In this brave new world of shattered traditional allegiances, Reform has led in every survey of opinion for more than six months and currently stands at 27 points in the poll of polls. Not bad for a pop-up party which has only been in existence for four years, but way below the levels of support which would fully justify Nigel Farage’s brag that he is going to be the prime minister. Labour and the Tories are knocking around 17 to 18 points. At the 1951 general election, their combined vote share was so colossal it came to nearly 97%. Today the former giants of our politics are so diminished that they can rustle up the support of barely over a third of voters. The Lib Dems are in the low teens. The surge to the Greens since Zack Polanski became the party’s leader has made them the first choice of voters under 35 and they sit at 14 points in the poll of polls.

That kind of multi-party divide will not startle you if you live in the Netherlands. This degree of fragmentation is familiar to many countries with proportional representation. Brexit Britain has weirdly ended up with a more European kind of politics. Which wouldn’t be such a headache if we were not still saddled with a first-past-the-post voting system, which is less fit for purpose than ever. Election results become wildly unpredictable when five outfits are in contention – six in Scotland and Wales – and none of the UK-wide parties has the support of more than one in three people.

Squint at the numbers a different way and you can see two big blocks. The combined score of the Tories and Reform amounts to 44 points. Put together Labour with the Lib Dems and the Greens and they come in at an identical 44 points. Who forms our next government could well depend on whether it is the right block or the left one which is the most splintered.

This poses large questions, one of which is whether parties should be thinking about electoral pacts. These are rare in Britain, but they have happened. The first Labour MPs entered the Commons in 1906, in part because the Liberal party agreed to stand down candidates in seats where Labour was stronger. The idea of forming a ”popular front” with other parties of the left has traction among some Labour people. The appeal is that it would reduce the risk of a split on the left letting in the right. But it is near impossible to see how a bargain might be struck. Neither Sir Keir Starmer nor anyone who might conceivably succeed him as Labour leader will sanction a seat deal with Mr Polanski, who has said, among other things, that the UK should leave Nato. The leader of the Greens recently told our political editor that there is “absolutely no way I would touch Keir Starmer with a bargepole”. He has no incentive to strike a bargain with Labour when he’s hoovering up a lot of its former support. As for the Lib Dems, a post-election deal with Labour in the event of a hung parliament is plausible. A pre-election pact is not.

Between the rival forces of the right, there’s social and ideological intermingling. At the Spectator magazine’s Christmas bash, Richard Tice, Reform’s deputy leader, was partying in the same garden as members of the shadow cabinet. Some Tories reckon their best hope of survival is to strike some kind of deal with Mr Farage to “unite the right”. Others fear that idea is an existential threat to the oldest of Britain’s parties. One Conservative peer tells me a deal with Reform would be “insane” for the Tories because “the smaller party always gets eaten alive.”

The Reform leader has little reason to parley anyway. He’s just bagged a whopping £9m donation from Christopher Harborne, an aviation entrepreneur who dabbles in crypto and takes a close interest in our politics from his home in Thailand. Twenty-one former Tory MPs have traded blue for turquoise by joining Reform in the past year, though Danny Kruger, the MP for East Wiltshire, is the only sitting parliamentarian to have defected. The Tories are constantly destabilised by rumours that more of their number are set to jump ship: Robert Jenrick has been forced to deny that he will do the rat run. Reform reckons it will come out on top at next May’s elections to the Welsh Senedd, Scottish parliament and in English local government. A deal with the Conservatives would undercut Mr Farage’s claim to represent a clean break with the politics of the past. Zia Yusuf, his head of policy, scoffs that “failed Tory MPs” are not likely to be chosen as Reform candidates. It is not in their interests to look like a refugee camp for discredited Conservatives.

The stage is being set for the next general election to be a high-stakes, high-wire, high-turnout affair in which the issue which most motivates voters is whether or not they want to see Mr Farage and his vulpine grin posing on the doorstep of Number 10. Labour strategists tell me this will suit them on the grounds that the spectre of a triumphant Farage will induce leftish voters to hold their noses and back Labour to stop it happening. It explains why Sir Keir is so keen to talk up Reform as his chief adversary and speaks of defeating them as a moral mission. In some circles this is known as “doing a Macron”. Emmanuel Macron twice beat Marine Le Pen in French presidential elections by projecting himself as “a barricade against the far right”. Tactical voting by anti-Reform voters helped see off the Faragistes in June’s Hamilton byelection, which Labour won, and in October’s Caerphilly byelection, where Plaid Cymru was the beneficiary. But tactical voting can cut both ways. Reform strategists think they can squeeze Tory support behind their man by consolidating right-wing voters who loathe Labour.

For all the apparent fragmentation of British politics, there’s a good chance that the next general election will turn into an extremely binary affair with one central question on the ballot paper: how much does the thought of prime minister Farage terrify you?

Related articles:

Photograph by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy