This story started in March. A friend sent me a link to a small British movie she’d worked on that hadn’t yet been released. It had been shot in Wales over 18 days on a tiny budget, and as the closing credits rolled, my tearful husband [Richard Curtis] said he thought it was one of the best British films of all time. We offered to host a screening and invited anyone we knew with media influence to watch the masterpiece that is The Ballad of Wallis Island to help spread the word.

A few weeks later, the co-writer and star of the film, Tom Basden, arrived with a thank-you gift: a plastic pot with a leafy stick in the middle. To be honest, I’d have preferred a scented candle, but I was touched that he’d brought it.

Tom then told me the story of the plant. This scrubby little sprig was a cutting from his begonia, which had started life as a cutting given to him by his father-in-law, the writer Barry Walsh, who had been given his plant as a cutting by the casting director Corinne Rodriguez in 2017. Corinne’s begonia had grown from a cutting of a plant grown from one given to her by the actor Sally Miles in the 1970s. Sally’s had started life as a cutting she was given by the opera singer Kirsten Flagstad in the 50s. And Kirsten had been given her cutting in the 30s by her dear friend … Sigmund Freud.

So there I was, moving from apathy to disbelief, holding the same plant my great-grandfather Sigmund had nurtured nearly 100 years ago. A cutting grows up to be a perfect clone of the original – no matter how many times you pass on cuttings of the cuttings of the cuttings, they’re all genetically identical to the original shrub. Sigmund died before I ever met him, but I now owned a tiny part of his story. A biological heirloom that had lived alongside him and brought oxygen into his pioneering study – growing alongside his evolving ideas, laying down roots as he laid down theories.

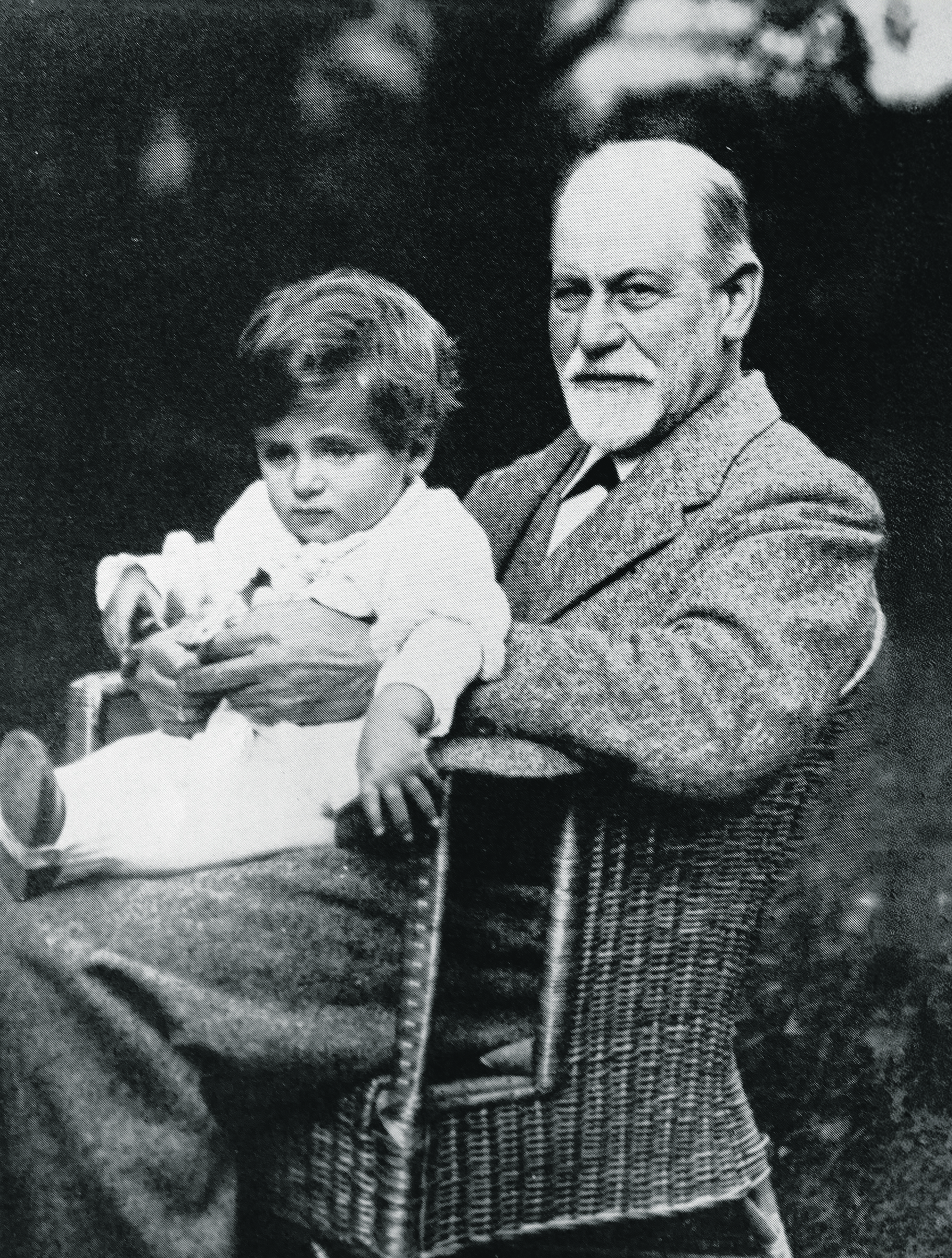

Sigmund Freud, who had form in horticultural gifting, nurtured the plant nearly a century ago after arriving in London in 1938

The Freud family all lived in Europe until my dad was eight, and were then together in north London for the last year of Sigmund’s life – he died when my dad was 15. But my father, Clement, was very uneasy about his grandfather’s legacy. He wouldn’t engage on the subject any more than by saying we should all stand on our two feet and not hang on to someone else’s coattails.

He worked hard to make his own name and avoided the subject of psychology entirely, along with his other pet hates of cigarettes, garlic, chewing gum, nail varnish, music, perfume and Dr Scholl’s sandals. On one occasion when he appeared on the Johnny Carson chatshow in the US, he had it written into his contract that he wouldn’t answer questions about Sigmund. Carson obviously sensed a story and asked the grandfather question, so my dad answered at length about his mother’s father, who had been a banker in Berlin.

By the time I was born, the word “Sigmund” was unmentionable in our house. The convent we attended was 100 yards from his old home in Hampstead, north London, and my sister once came home from school saying: “The nuns mentioned someone called Sigmund Freud and said I should know who he is.”

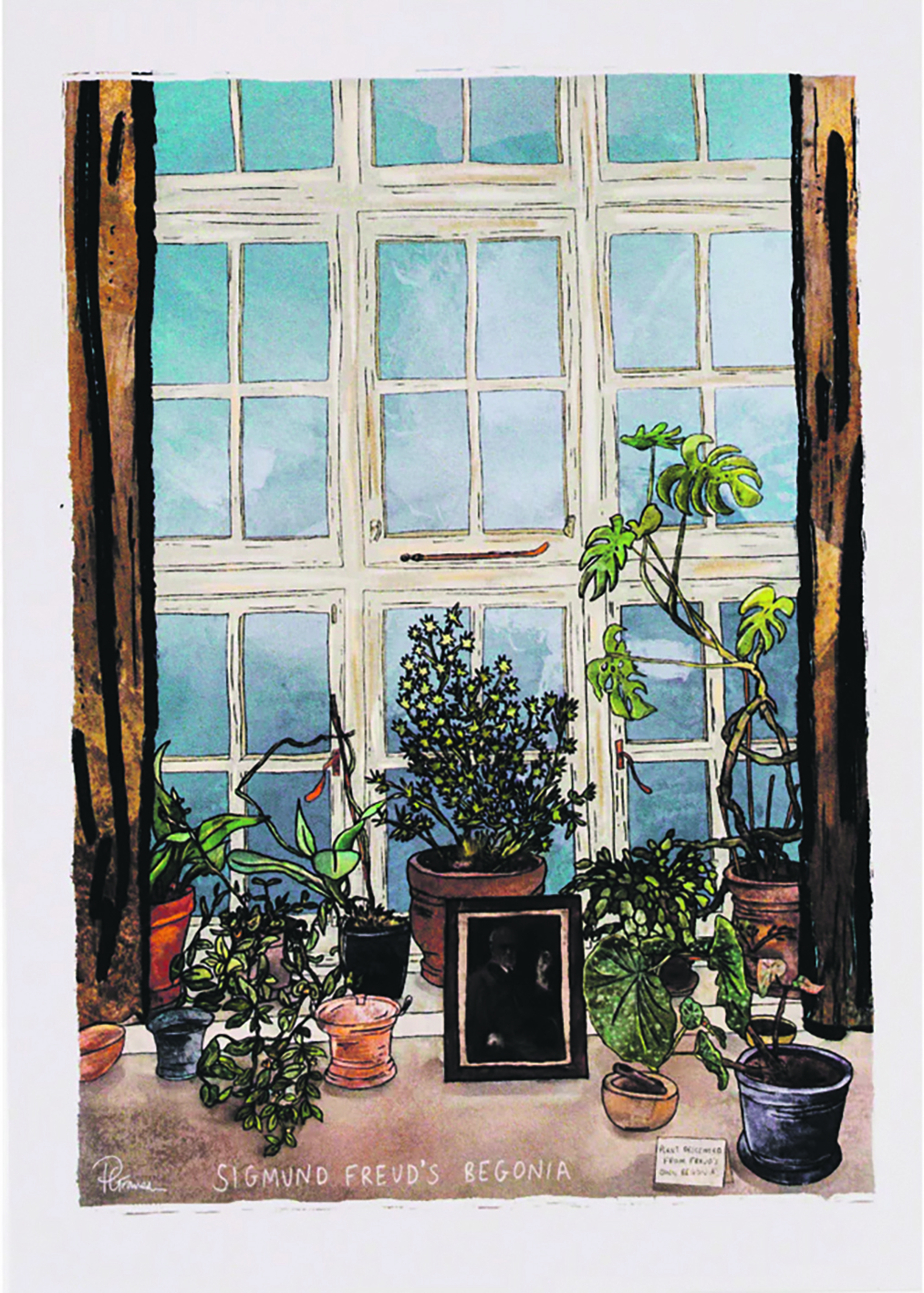

The begonia is depicted by Portia Graves

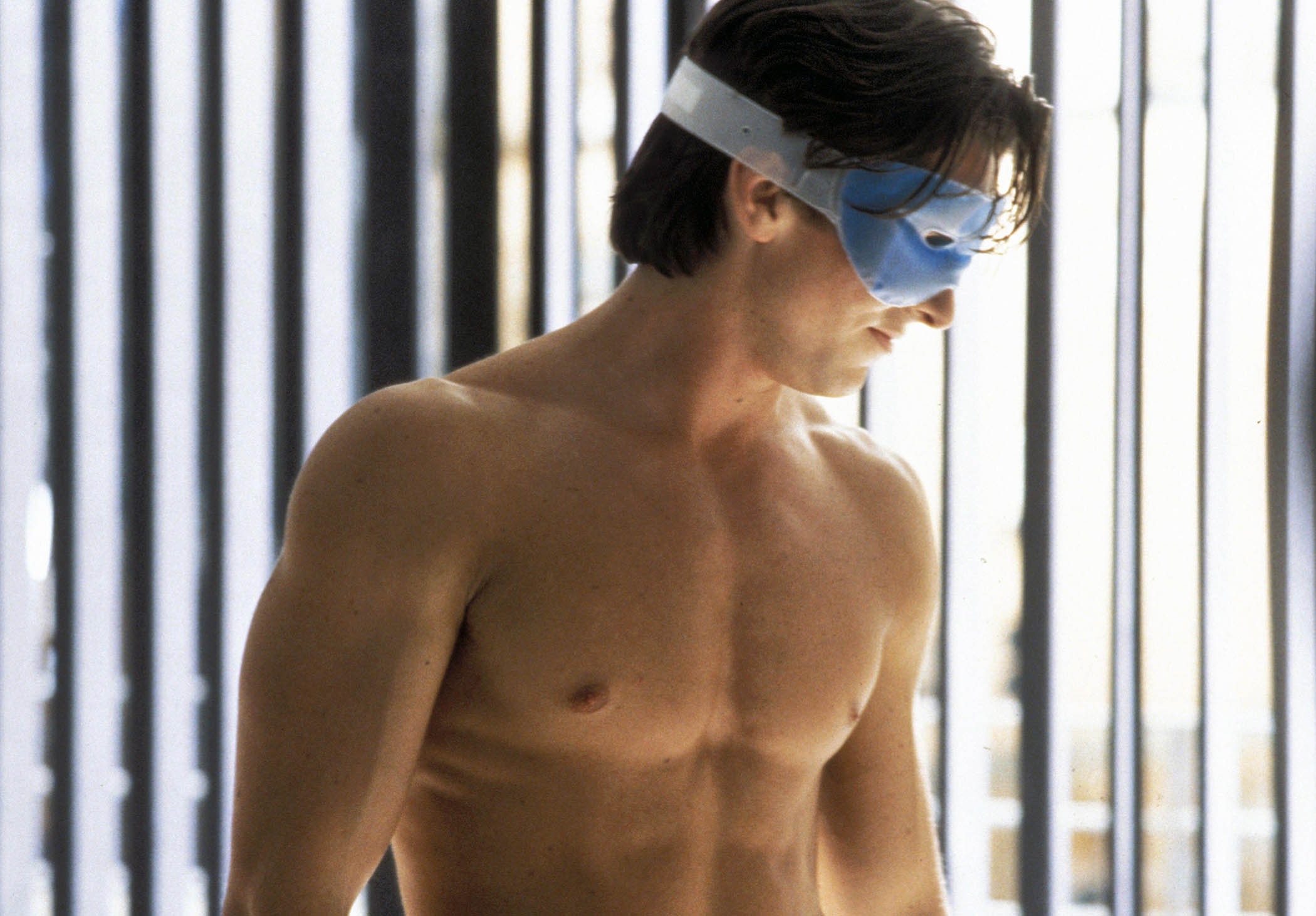

Tom Basden, who gave Emma the begonia as a thank-you gift

“Ah,” said my father in a serious tone (his only tone). “That’s awkward. He was my grandfather; he invented the flush toilet. If anyone mentions his name again, change the subject.” My sister believed this for years.

So the five of us grew up with no knowledge whatsoever of our ancestry. There were no books by or about Sigmund in the house, no photos, stories, mementoes – just a freezing of the air if anyone ever mentioned him in dad’s company. Even now, 16 years after my father died, I’m feeling slightly frightened that I may get into trouble for writing about his grandfather.

So as I placed this stumpy green stick on the mantelpiece in my sitting room, I realised it was the only thing I have ever owned with any connection to the man who transformed the way we think about ourselves, and who was also my great-grandfather. He had been sitting in the shadows my entire life until – unexpectedly, in my 60s – someone I barely know shone a tiny light on him. Like a detective who has no idea what they’re looking for, I decided to dig deeper into the chain of events that led finally to my owning a tiny piece of this past.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

I looked up the qualities of begonias and found they’re often given as a gift to repay a favour. I knew Tom had given me the cutting in gratitude, but why had his father-in-law given one to him?

BARRY

Barry Walsh – now virtually my best friend after the number of emails we’ve exchanged about pot plants – wanted to thank Tom for a family holiday he’d organised to Wales. But I’d like to imagine he was also thanking his son-in-law for giving us the fabulous sitcom Here We Go, being nominated for three Baftas, and generally being both funny and clever.

Now a novelist, Barry started his working life in the 70s as a press officer at the Mermaid theatre in London

CORINNE

Barry is now a novelist, but had started his working life in the 70s as a press officer at the Mermaid theatre in London, where he worked alongside the renowned casting director Corinne Rodriguez. As a teenager, she was in charge of Liberace’s fan club, but was expelled for bunking off school to watch him. Without qualifications, she became a typist at the Royal Court theatre, before becoming its youngest casting director. In 2008, Corinne was diagnosed with cancer, and not long before she died, she gave Barry a gesture of thanks for their four decades of friendship: a cutting from the precious begonia that had been given to her by the actor Sally Miles.

Corinne Rodriguez gave a cutting to her long-time friend Barry Walsh (pictured together

SALLY

Sally had a lot to be grateful to Corinne for. She’d cast Sally in many plays and productions. As well as acting, Sally was a singer, comedian, director and designer – a dynamo with the same work ethic as her father, the eccentric actor and director Bernard Miles, who spent much of his life with his pet parrot on his shoulder. Bernard ran the Mermaid theatre, where he’d employed the Norwegian opera legend Kirsten Flagstad, and it was there that Kirsten gave a cutting from her precious begonia to Sally. But why?

Sally, pictured with her father Bernard who ran the Mermaid theatre. She inherited a cutting from her godmother Kirsten, who was also her father’s muse

KIRSTEN

Considered the greatest Wagnerian soprano of the 20th century, she was as famous in her time as Maria Callas, but her career was damaged after the war when her husband was imprisoned under suspicion of Nazi involvement. Kirsten herself had strongly supported the resistance, but in 1947 American audiences booed her as she arrived on stage.

With a blackened public image, the recently widowed Kirsten came to London in 1948 to perform in a fundraising concert for the United Jewish Appeal. It was there that she met Bernard Miles, and they instantly became friends. When she later visited his house in St John’s Wood, he showed her a large building still standing in his garden from the days when the house had been a school.

It had a wonderful acoustic, and that afternoon, they made a deal that would go on to change one little corner of British theatre: if he refurbished the barn, she would perform on their opening night. The original Mermaid theatre, a 200-seat venue with an Elizabethan stage, opened in Bernard’s back garden in September 1951. It sold out its first 20 performances of Dido and Aeneas starring Kirsten as Dido and received rave reviews. There was a Mermaid theatre in London from that day for the next 57 years.

Kirsten’s damaged reputation had made her vulnerable. She was grateful that Bernard had given her this chance to perform in London, and he was grateful that she’d launched his theatre. It was at this point that Bernard asked her to be Sally’s godmother, which Kirsten acknowledged by giving her new godchild a cutting from her precious begonia.

Sigmund gave a begonia cutting to the celebrated Norwegian opera singer in the 1930s. She moved to London soon after the war

But here’s the curious thing: Sally was 17, which is an odd time to gain a godmother. There must have been a reason why the Miles family wanted to cement Kirsten into their family, and I couldn’t work it out. I continued digging and found Kirsten’s contract for Dido at the Mermaid.

The Singer undertakes …

To be obedient, tractable, sweet tempered and helpful in every possible way

To let The Management look down her throat with a laryngoscope whenever they need encouragement

and she promises not to brag about the Vikings.

The management undertakes…

To hold The Singer dear, to prize, treasure, cling to, dote on, adore and idolise her

To supply her with 2 pints of oatmeal stout per diem, viz. lunch 1 half pint, dinner 1 half pint, and 1 pint following each performance

To give her little surprises, write her letters and poems, and take every opportunity to make her laugh.

This isn’t the professional contract you might expect a theatre to present to an iconic opera singer – it reads more like a playful love letter. Digging deeper, I found Alan Strachan’s biography of the Mermaid theatre, which contains Bernard’s admission that he “fell in love with [Kirsten] the moment I met her … I could see and think of nothing else for four or five years.” To a recently qualified amateur detective like me, this was a revelation.

It consequently turned out the Mileses were as unconventional at home as they were in their theatre. Bernard said that his wife, Josephine, “like a good wife, as always, wanted me to have what was good for me”. They were an unorthodox family. Josephine was herself having an affair with the female novelist Noel Streatfeild, who wrote Ballet Shoes. She clearly agreed to her husband’s girlfriend’s appointment as Sally’s godparent. Years later, Sally even called her daughter Dido, after Kirsten’s most famous opera role.

By this stage, I was becoming obsessed with my begonia’s history. I went in search of the original Mermaid theatre. Available records only showed the street it had been on, so I knocked on all the doors until I was eventually pointed towards a “Mermaid House”. I sneaked through the gates, but the theatre had been demolished.

At home, I tried to uncover the original plans of the building, and in this strange tale of plants, presents and uncovered family histories, it turned out the architect of the first Mermaid theatre was none other than Sigmund’s son, my grandfather Ernst Freud.

Ernst (Pap), his wife, Lucie (Mutti), my father Clement and his brothers, Lucian and Stephen, had lived in Berlin, but in 1933 Hitler was appointed chancellor and, as Jews, their city was no longer safe. We were told that Ernst emptied his bank account, hollowed out a leg of his dining table, filled it with cash and took his family – and his table – to London. This family of refugees settled into a little terrace house in north-west London, one block from the home of Bernard Miles.

SIGMUND

So why had Sigmund given Kirsten that first begonia cutting back in the 1930s – in Vienna? – was it her celebrated voice? That seems improbable – like my father and my daughter, Sigmund disliked music. Its effect on him was powerful but any feeling he couldn’t control made him uncomfortable: he once said “something in me rebels against being moved by a thing without knowing why I am thus affected or what it is that affects me”.

However, he did have form in the horticultural gifting department. When Virginia Woolf met him in 1939, he famously (and possibly rudely) gave her a narcissus. When I dug into his history – something I’d avoided doing for so long – more plant-based activity emerged. Despite growing threats, Sigmund stayed in Vienna until 1938, at which point he and his wife were taken to London. Had he stayed longer, he may have ended up dying in the camps like all four of his younger sisters. It’s documented that among the possessions he brought with him on that final, life-saving journey were his famous couch and a zimmerlinde plant from his Vienna apartment, from which cuttings were taken and shared. It was later immortalised in my uncle Lucian Freud’s painting Still Life with Zimmerlinde, which sold for nearly a million pounds in 2018.

The terrace house in Hampstead, north-west London, where the Freuds lived. Sigmund’s house is now the Freud Museum, and home to the famous begonia

This information was opening doors I’d never thought I’d go through, but one door led to another and finally there was a big one in front of me with my uncle’s name on it. My father Clement’s broken relationship with Sigmund was echoed by a broken relationship with his brother Lucian. His mother once told him she only had enough love for one of her sons, and it had gone to Lucian. By the time they got to adulthood, they were worlds apart. Lucian still spoke with a strong Germanic accent, my father sounded, and was, entirely British. I didn’t even know he could still speak German until, in my 40s, I heard him talking fluently to a taxi driver in Berlin.

The last time my father saw Lucian was in the 1960s, when he dropped into a cafe in Camden and the only available table was a shared one. The waiter asked a man already seated if he would be happy to share his table. Lucian looked up, saw his brother, turned to the waiter and said no. They never saw each other again.

I only ever had one conversation with Lucian. It was the day after my father’s funeral in 2009 and I went for dinner at his favourite restaurant. By strange coincidence I found myself seated at the next table to one of my closest friends, Esther, and her father, who I didn’t know … Lucian. She introduced me to my uncle. It didn’t go well. He said: “Ah, Clement, vot a cunt.” I never saw him again.

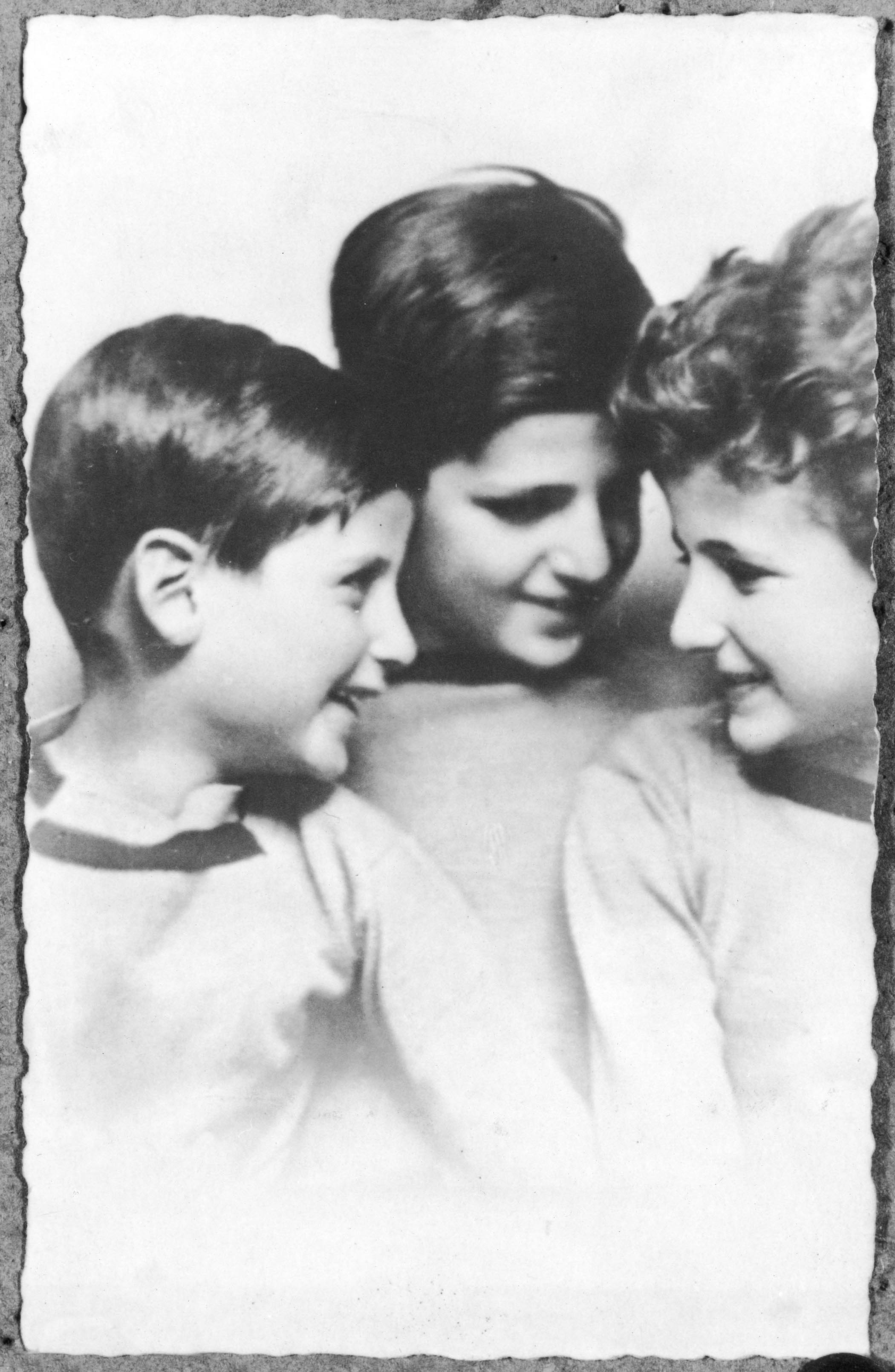

Sigmund’s grandsons Clement, Lucian and Stephen

When Lucian died in 2011, he left his house in Kensington to his assistant David Dawson. On my plant mission, I set aside the fraternal feud, put on my big girl pants and tracked down an email address for David. His reply was instant: “Tomorrow at 3pm.” After all these years, I was going to visit Lucian’s house for the first time, and hopefully take away a tiny piece of his history, and a symbolic emblem of our disjointed family tree.

Lucian’s home turned out to be a five-minute walk from the house in Notting Hill where I had lived for 30 years. I asked David if Lucian, like my father, had a strange relationship with Sigmund’s legacy. “No,” he said, “not at all. He was at ease with it – used to tell stories about him from their childhood.” There are stories?

“Well, you know the one with the teeth, obviously.” I did not know the one with the teeth or any other. “Sigmund used to go behind a screen in his examining room with two pairs of dentures and hold out his hands to the side of the screen while the dentures chatted away between themselves.” A cracking Sigmund anecdote. My first. David kindly gave me a cutting from one of Lucian’s zimmerlinde plants that Lucian had claimed came from one of Sigmund’s. It now lives on my mantelpiece next to Sigmund’s begonia.

My final field trip was to Sigmund’s house in Hampstead. It was here he spent his last year, riddled with cancer, before his doctor administered a lethal dose of morphine for a death by assisted dying. It’s a museum now – I paid my £14.50 and walked into the heart of my family history. The exhibits included photographs and grainy videos, and I don’t know what the other respectful viewers thought when I involuntarily shouted out “It’s Mutti!” at one piece of footage. And there on a wide landing, soaking up the sunshine, stood the famous begonia. The source of my plant’s DNA in a house that contained a lot of my own. It’s a peaceful and grounding place to be. My roots are here – it just took me a while to find them.

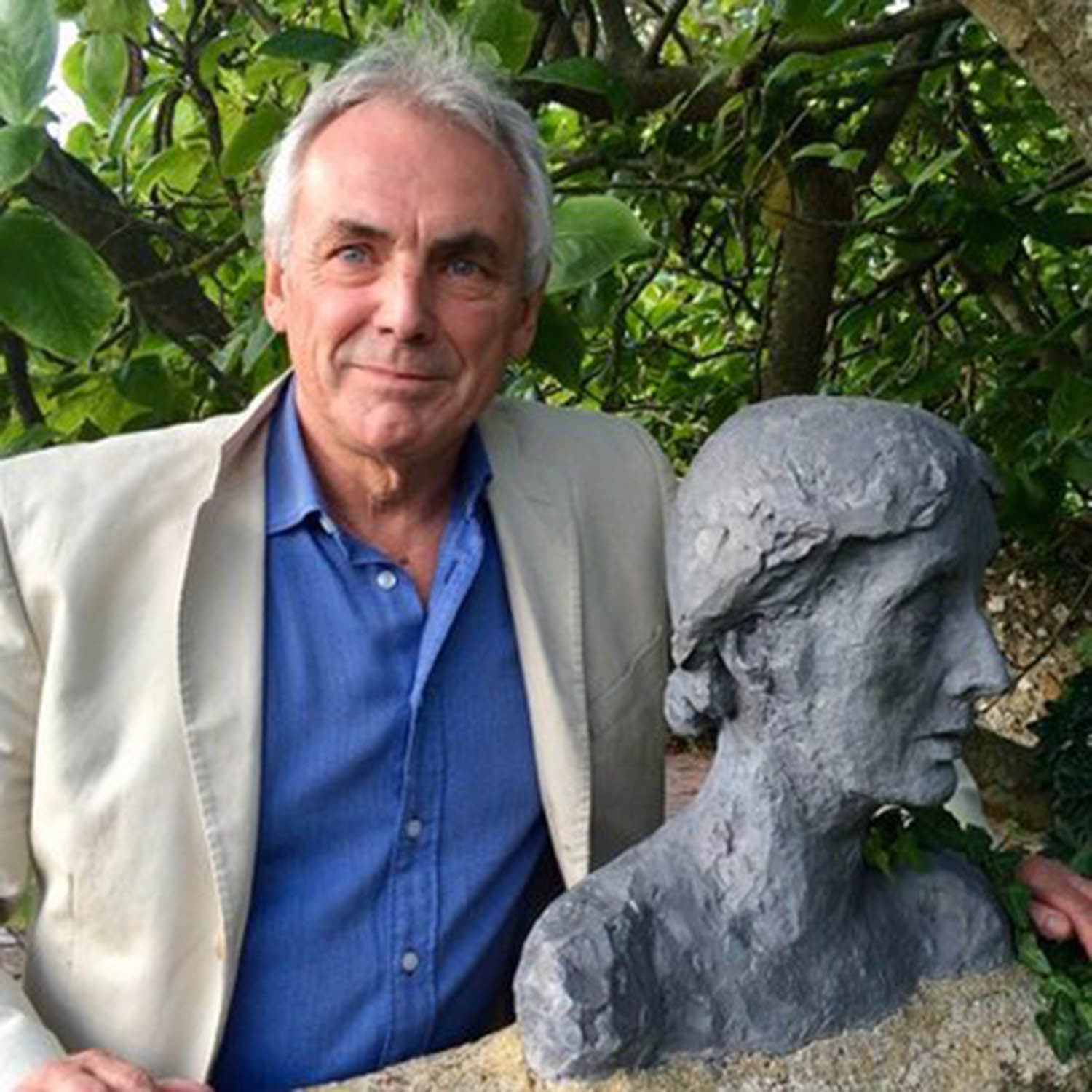

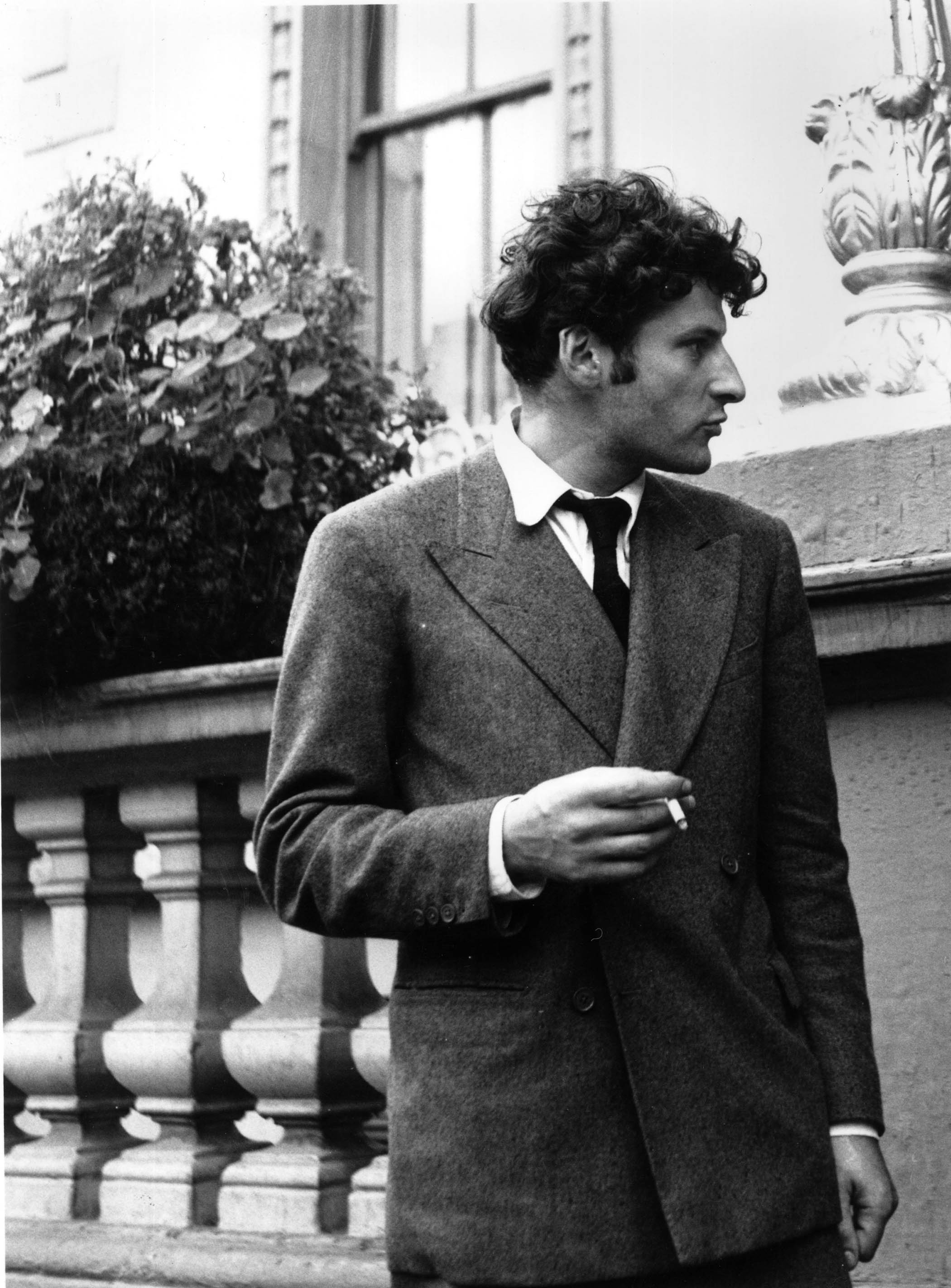

Lucian Freud was estranged from Emma's father

Lucian Freud’s Still Life with Zimmerlinde, which sold for nearly a million pounds in 2018

Francisco, the museum’s caretaker, sells cuttings from the special plant to help fund the running costs of the museum. “We used to ask for £30 each, but as we don’t have many, we’ve raised the donation according to demand – it’s like the London Stock Exchange,” he said. “We’ve only got one at the moment, so it’s £80.” I told him I was writing an article about the plant. “Oh no,” he said. “I’d better get more jam jars.”

I realise now this isn’t the first time I’ve discovered my family through the kindness of friendship. I got to know Lucian’s daughter Esther not because she’s my cousin, but because our mutual closest friend introduced us in our 30s. Like my cutting, had it been left to our blood ties, we wouldn’t be in each other’s lives. We met through friendship, and now live next door to each other.

Sigmund was a disruptor who shone a light on the significance of early experiences in shaping behaviour. My early relationship to my lineage was shaped by my father’s anxiety about acknowledging where he came from. I accepted that family blackout, because to question it would have been like talking about a flush toilet.

But over recent weeks, a small horticultural cutting has transformed the way I now see my family tree. My father was forced to leave his homeland, and in order to assimilate he turned his back on his culture and language. He was rejected privately by his own mother, and publicly by his brother. And around his neck was a surname that instantly linked him to his roots, and his complicated past. So his phobia about anything connected to the Freud legacy might have been his coping mechanism – a personal rejection of the people and the country that rejected him.

So that’s my begonia tale. I’ve been Sigmund’s great-grandchild since 1962 and, through that bloodline, I had little to show for it. But through a long chain of gratitude, kindness, friendship (and lust), a small green and purple plant has rooted me in the topsoil of my past. In the end, it was friends and strangers who allowed me to let go of an inherited distance from my past relatives and introduced me to my strange and guarded family.

My cutting has just propagated its first new shoot. I will pass it on with love.

Portrait by Emma Hardy for The Observer. Photographs by Alamy/Getty Images/Freuds Cards/Barry Walsh/