I first got to know Patrick Bateman when I was 12. I watched him glove up and hack away at female bones, bind his victims and make them wait, duct-tape their baffled, gaping mouths. At that time, on weekends, I was allowed to go into town alone and idle about, and I used this freedom to abuse the bookshop, reading novels I didn’t have the permission or money to actually acquire. Every Saturday, for three months, I went in and read a few chapters of American Psycho, aghast and with my hand to my throat, sometimes from uncomfortable laughter and sometimes from pure shock.

Not long ago, I recounted to my boyfriend some of the things I can never forget. He flinched as I described Bateman electrocuting a woman and the fat from her breasts splattering the venetian blinds. I don’t recall all that much from my childhood, and images from books make up many of the more enduring, vivid memories. That explosive fat; Bateman blinding a homeless man with a knife then breaking his dog’s front legs. I wonder what I was so compelled by as a child, because I wasn’t intelligent enough to appreciate the irony, and I was often bored by the brainless serial killer films I stayed up to watch. I think part of me sensed there was something more to be understood, something I could not yet grasp.

I grew up, and read it again, and as an adult, found it funny as well as horrifying. The rigidity, the hysterical fixations, the compulsive analysis of pop songs. The movie was good, too, and I felt validated in my childhood taste. I lived in Ireland and was oblivious to the context of Bret Easton Ellis and his literary brat pack, but I was intrigued.

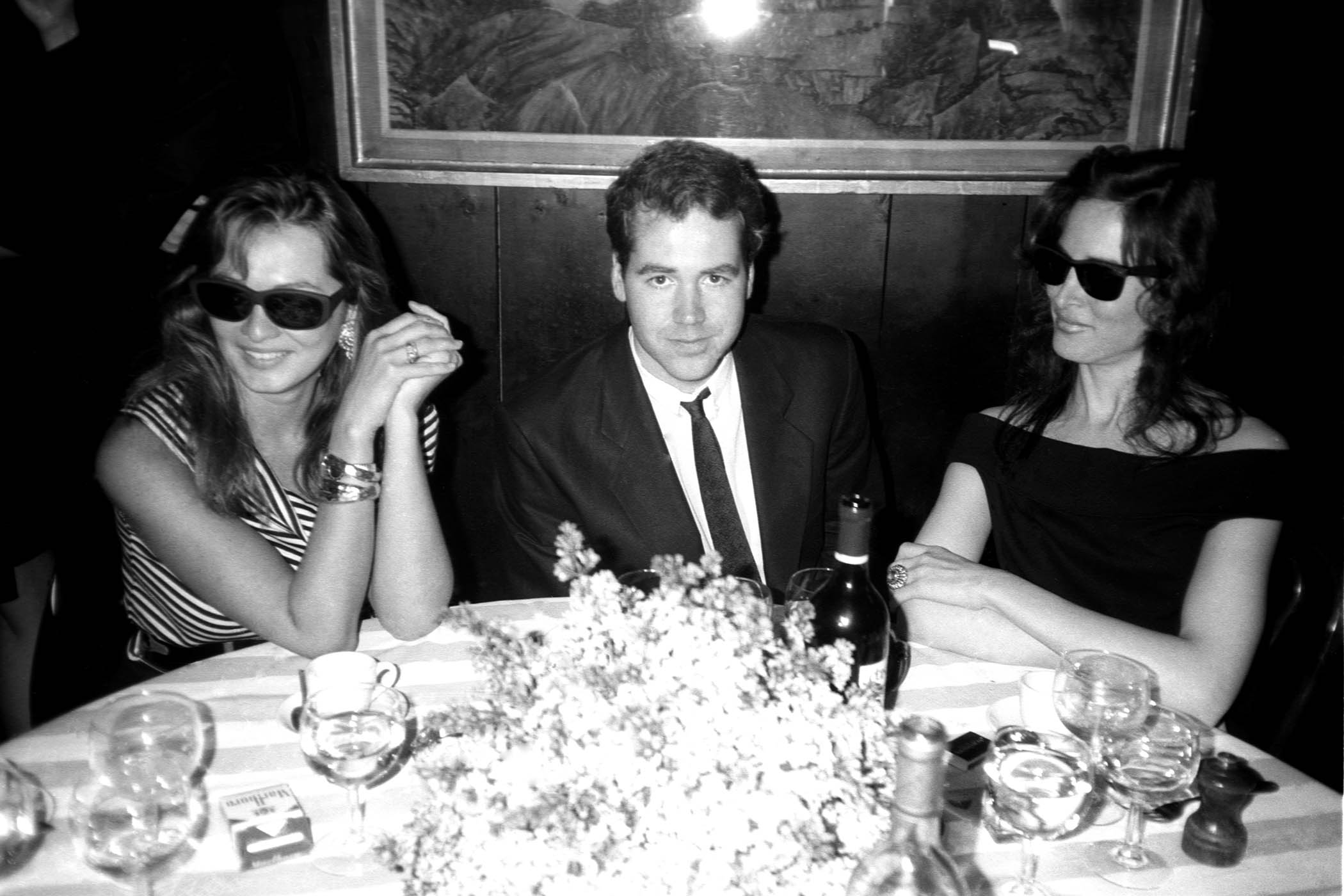

Author Bret Easton Ellis, centre, in New York in 1987 with friends wearing Bateman-style blackout sunglasses

Then, in my 20s, I began to see Bateman Halloween costumes, always worn by the exact demographic of person the book was, I assumed, satirising: wealthy, status-conscious, nondescript, handsome white men in upwardly mobile careers. When I started using dating apps for the first time, it was not uncommon for men to have a picture of Bateman among images of themselves. Later, on TikTok, I saw users posting clips of Bateman performing his skincare routine with captions that simply read: “Me.” Those affectations of Bateman’s were supposed to be sad – an insight into his vain solipsism – but I began to realise that there was an alternative reception of this character I did not understand at all.

Who is Bateman, anyway? He’s nothing – an endless void. He’s the personification of the roiling anxiety that whatever a man says or does can never be good enough. Bateman is utterly free of authentic desire or self-direction. The comedy of the novel and the film relied on the audience understanding that this is a loathsome and ultimately impossible way to exist, but a swathe of them decided to either ignore or ironise their way out of this.

Instead of receiving Bateman as a plainly pathetic figure, they registered only his ostensible successes in the narrow field of victory he is landlocked in. He’s lean, and hot, and rich, so he is a hero, never mind the existential agony, or even the murders. But there’s something else, too; after all, there are plenty of cultural figures who are handsome and rich and fit. They are attracted to Bateman specifically. His underbelly is valued; it’s as though the inherent femininity of wanting to appear perfect and appealing is subverted by his monstrosity.

Bateman is obviously and transparently desperate, so it’s no surprise he should be an increasingly present icon for our era. He is isolated to a degree that is impossible to broach. There is something deeply American about this: the US has always romanticised the individual, and this particular moment has hardened that impulse into something ugly and volatile. The cultural critic Lee Siegel wrote in the New Statesman in 2024: “America still has not plumbed the weird depths that the fusion of its politics with its loneliness could lead.” But the US is certainly trying its best.

Bateman skewered a particular yuppie Wall Street archetype of the 1980s, but the isolation, vanity and vacuity he exemplified are far more overt now. Bateman’s hero, Donald Trump – he references Trump throughout the novel and in the film the character cherishes his copy of The Art of the Deal – is an enigmatic emblem of loneliness. Trump’s fellow military school cadets have spoken of being around him constantly but never knowing him at all. He arrived clueless about making beds and shining shoes but soon thrived on the rigidity. What could be more comforting for the person with no centre than a world where each action is mandated for you?

Related articles:

You wonder if there is some part of Trump that is panicked and detests the fact he now decides everything, is the ultimate master of the universe. It must be a particular loneliness to have the world at your disposal and yet still be stuck with yourself.

He exemplifies isolation, vanity and vacuity. His hero, Donald Trump, is an enigmatic emblem of loneliness

He exemplifies isolation, vanity and vacuity. His hero, Donald Trump, is an enigmatic emblem of loneliness

American Psycho was published in 1991, and part of the appeal of its operatic rendering of misogynistic hatred was to do with the broad movement towards political correctness. At that point, though nobody imagined misogyny or other such feelings had disappeared, it was culturally unacceptable to be blatant about them. The repression of urges such as these – the urge to treat women like property, say – leads to those feelings being sublimated, perhaps through the fictional character of a status-obsessed man who murders women in a frivolous, almost comic manner.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In 2026 misogyny is a different beast, certainly on the post-Trump internet. After the 2024 election, teenage boys told their female classmates: “Your body, my choice.” While it’s true that your average college professor would do well not to viciously insult women for being women, it is also true that there are men who are famous and rich, not in spite of, but because of their extreme misogyny: Andrew Tate, for instance, who describes how a woman is to be owned as you might own a dog.

Within the manosphere, there is the phenomenon of “looksmaxxing”. This is a practice born out of the incel realm, where men try to improve their physical appearance through often extreme interventions. It’s a consequence of the subculture’s “black pill” theory that physical appeal is the only relevant factor in attraction, and that those cursed with ugliness are doomed to be alone. Looksmaxxing is the attempt to improve your appearance as much as possible, going beyond the usual pursuits of skincare and fitness, into a much odder and darker place.

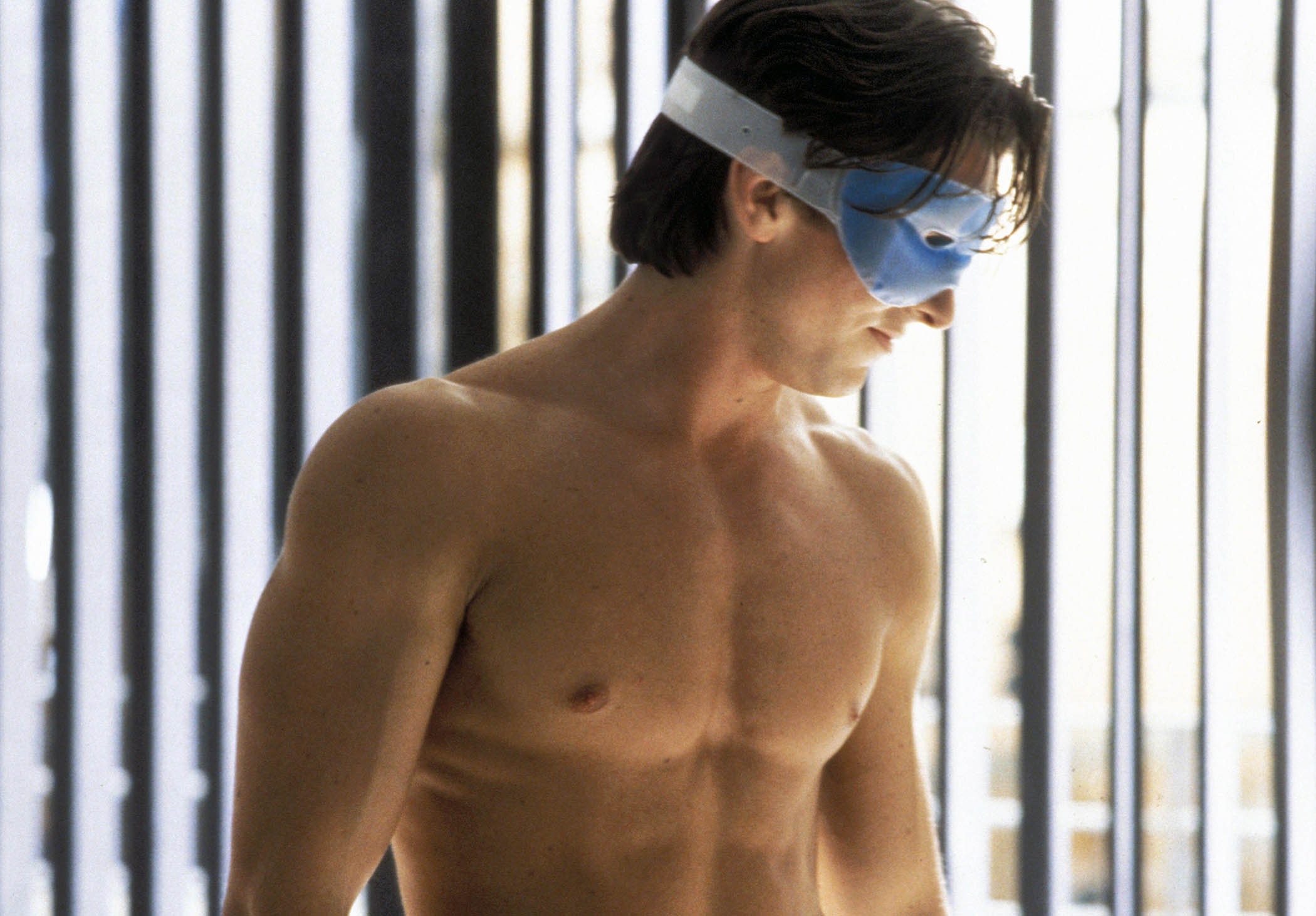

Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman in the 2000 film of American Psycho

Bateman, played by Christian Bale, tells us in the film version of American Psycho: “I believe in taking care of myself, and a balanced diet and a rigorous exercise routine. In the morning, if my face is a little puffy, I’ll put on an ice pack while doing my stomach crunches. I can do a thousand now. After I remove the ice pack, I use a deep pore cleanser lotion. In the shower, I use a water activated gel cleanser... Then I apply an herb-mint facial masque which I leave on for 10 minutes while I prepare the rest of my routine.”

Looksmaxxing goes much further. A Miami-based influencer known as Clavicular, a 20-year-old whose real name is Braden Peters, has written about injecting himself with testosterone, and advocates the use of crystal meth to curb your appetite and keep yourself lean, and – perhaps most notably – recommends smashing your bones with hammers to improve the quality of your jawline.

He has said that he does all this because he wants to use his good looks to acquire political influence, which is worrying, as his political ethos has so far been revealed chiefly through saying he wouldn’t vote for the US vice-president JD Vance who he described as appearing “subhuman” and “obese” but would vote for California’s governor Gavin Newsom (a good-looking “6ft3 chad”), and through singing the N-word in the Kanye West track Heil Hitler, along with Andrew Tate.

Bateman’s relationship to race is addressed only in passing in the book. Yet there is something crucial about his whiteness to his essential absence. His relentless efforts to reference popular culture, from Huey Lewis to Whitney Houston, is in conversation with the existential insecurity of white culture in the US. His lack of self leads to a diffuse and incoherent rage. America’s lack of definable identity, which is actually its greatest trait if it could only be accepted, fuels cruelty: a thirst to eliminate and punish those who suggest the possibility of plurality. Racism is implied in any supremacy-based ideology, and pseudoscientific eugenic theories are routinely peddled in such spaces.

American Psycho proposed an inevitable malevolent underside to a masculinity that is hyper-focused on supremacy. But perhaps not even Ellis could have anticipated a future in which society’s successful men are merrily smashing their own faces in with hammers.

Photographs by Alamy/Patrick McMullan