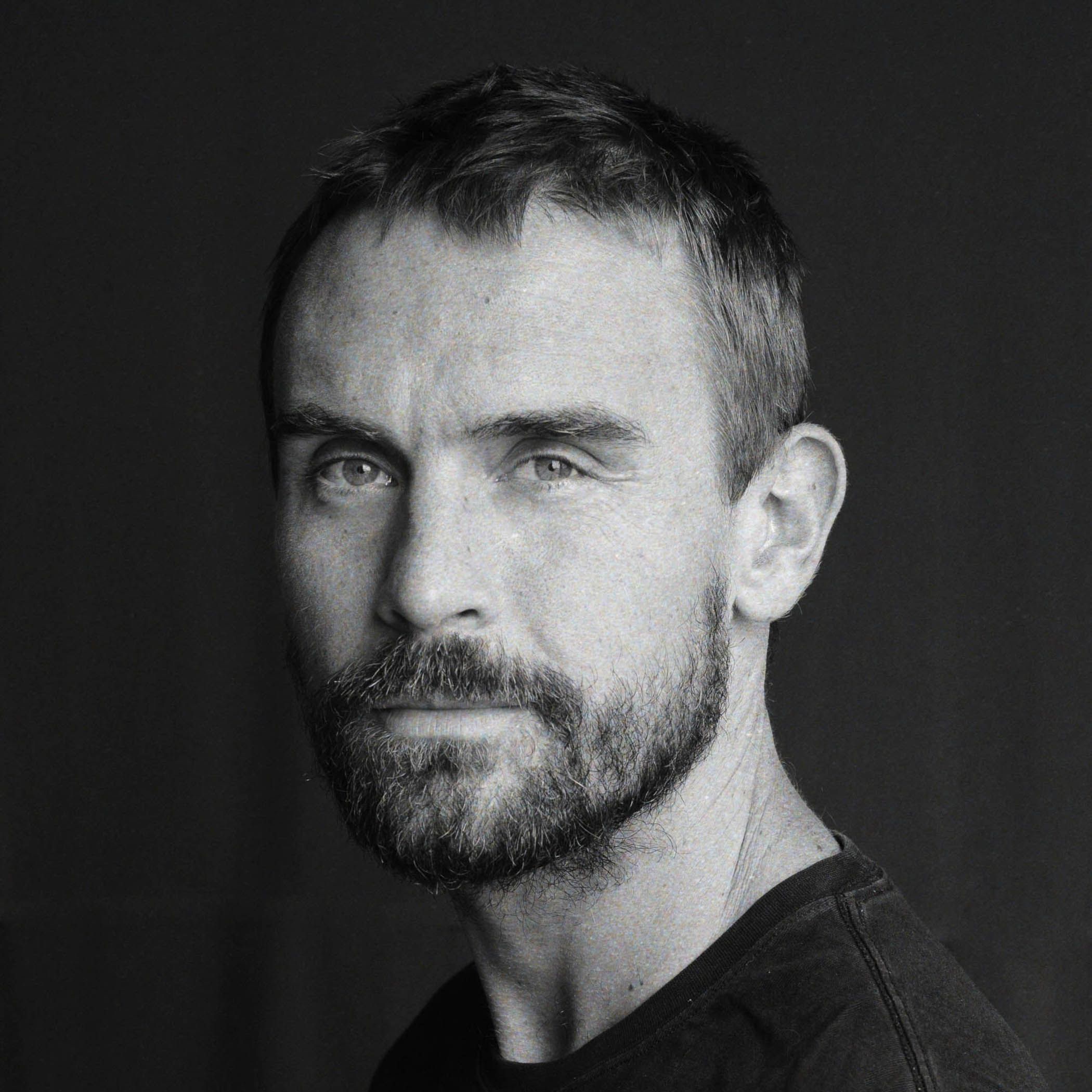

Ziad Roum began to cry as he described the moment he had learned that his two brothers, Imad and Jihad, were finally to be released after 23 years in Israeli prisons.

“You can’t imagine how it feels,” the 65-year-old Palestinian said. “My feelings are a mixture of joy, sadness and concern.

“We were [watching] the news constantly, trying to figure out what was true and what was not.”

From his office in Ramallah, electrical engineer Ziad – once an actor and producer – scrolled endlessly through messages from relatives as news of the ceasefire deal broke.

His brothers’ names were on the list: among nearly 2,000 Palestinian prisoners who are set to be swapped for 48 Israeli hostages, 20 of whom are believed to still be alive, under a deal approved by Israel’s Knesset after Donald Trump’s peace plan landed in Jerusalem.

Under the agreement, Israel will release 250 Palestinians convicted or suspected of security offences, along with 1,700 others detained during the Gaza war, and the bodies of 360 fighters.

Prisoners detained in Gaza will return there; those convicted of killing Israelis will be released in Egypt and barred from ever returning to Israel or the West Bank. Missing from the list is Marwan Barghouti, arguably the most popular Palestinian politician, who led the second Intifada, the Palestinian uprising against Israel in the early 2000s.

For Ziad, the news of the agreement marked the end of a two-decade wait. Imad and Jihad, now in their 50s, were given life sentences after being accused of involvement in the killing of two Israeli reservists in Ramallah at the height of the second Intifada in 2000.

The uprising, which was triggered by years of Israeli occupation, quickly turned violent. Within weeks, more than 100 Palestinians were dead, which led to a period of heightened violence, including shooting attacks, suicide bombings, and military operations, until 2005 when hostilities ended.

Reports claim that the two reservists, Vadim Norzitch and Yosef Avrahami, had mistakenly driven into Ramallah and were detained by Palestinian police. As word spread that they were there, crowds attending a funeral for Palestinians who had been killed days earlier descended on the police station.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The crowd overran the officers and killed the two soldiers. One young man, his hands red with blood, was filmed showing them to the cameras – a scene that burned itself into Israeli memory.

Ziad insists that his brothers were not involved in the incident.

“Israel never presented any definitive proof in court,” he said, his phone vibrating with messages. “But they maintain that they have enough information.”

For almost a year, the Roum family has lived between hope and heartbreak. In January, when other high-profile prisoners were released into Egypt, Israel barred their families from travelling to greet them. Anticipating the same, Ziad’s other siblings travelled to Jordan last week, waiting to see if they would need to continue on to Cairo.

Ziad stayed behind just in case his siblings were released in Ramallah. Yesterday, once he was certain his brothers would end up in Egypt, Ziad made plans to travel to Jordan and then on to Cairo with the rest of his family, if he is allowed to cross the border.

Following the Hamas attacks on 7 October 2023, Israel cancelled all prison visits, leaving many families cut off from each other. Ziad hasn’t seen his brothers in two years. Their mother died in April.

“It’s their lives, but I would like to see them get married. It was a dream of my mother’s,” Ziad said, breaking down in tears again. “With no visits allowed, even from lawyers, my brothers still don’t know that our mother is dead.”

The exchange is expected to take place tomorrow, timed to coincide with Trump’s visit to the Knesset.

But what comes after the photo op? The “Gaza peace plan” has left experts uneasy.

Its centrepiece – the gradual recognition of a Palestinian state – lacks clarity on borders and governance. The West Bank, home to more than 3 million Palestinians, remains conspicuously absent from the deal’s framework.

Packing up his things to leave for Cairo, while calming agitated relatives on the phone, Ziad’s focus narrows to the only thing that matters to him now: hugging his brothers after 23 years apart.

Before leaving home, the former actor pauses for a moment and reflects.

“In my head, the happiest ending to this movie is to have our rights, our state and to live freely,” he says. “But in reality, I just don’t know if it will happen.”

Photograph by Mahmoud Illean/AP