Dusk was falling as Israeli military vehicles drove into al-Mughayyir, a village of about 3,000 residents perched above olive groves in the occupied West Bank last month.

Hours earlier, young men from the village, which is located north-east of Ramallah, had clashed with Israeli settlers who have been encroaching on their village in a campaign of violent intimidation that has made life untenable for many Palestinians here.

After coming home from work, 18-year-old Hamdan Moussa Abu Alia got changed, ate dinner and told his mother he was going out. “I told him not to,” she recalled. “I told him the army and settlers are there.”

Her youngest son did not listen.

Escalating attacks by settlers had driven him to despair, she said. They had torched the family home and shot his elder brother in the leg during a rampage through the village last year. Before going out, Abu Alia mentioned he was going to look at a fire lit by the settlers, his mother said. As a volunteer in the local civil defence forces, he was involved in responding to settler attacks.

Within 10 minutes, he was dead. The Israeli military said it had opened fire after “terrorists” threw rocks and molotov cocktails at troops. “A hit has been identified,” it said in a statement. A grainy video filmed from a window captured Abu Alia making a dash between two buildings before toppling over.

What unfolded in the village over the following week would reveal the battle lines between settlers and Palestinians over control of the West Bank. Abu Alia’s death began a spiral of violence that culminated in a full-blown siege of al-Mughayyir, raising questions about the legality of Israeli military actions, and revealing the overlapping agendas of radical settlers and the state.

Related articles:

As the UK and other western countries have dithered over the question of Palestinian statehood, Israel has been taking active steps to foreclose it. Across the West Bank, it has enabled radical settlers, who are rapidly expanding their presence in territory that would make up the bulk of any future Palestinian state.

The process accelerated after Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, returned to office in 2022 with the support of far-right settlers who claim all the West Bank as Israel’s birthright. His coalition brought a messianic movement from the extreme fringes of Israeli politics into the heart of the establishment.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

With attention on Gaza, the government has advanced policies that are driving Palestinians into shrinking pockets of the West Bank. Swathes of the territory have been declared state land.

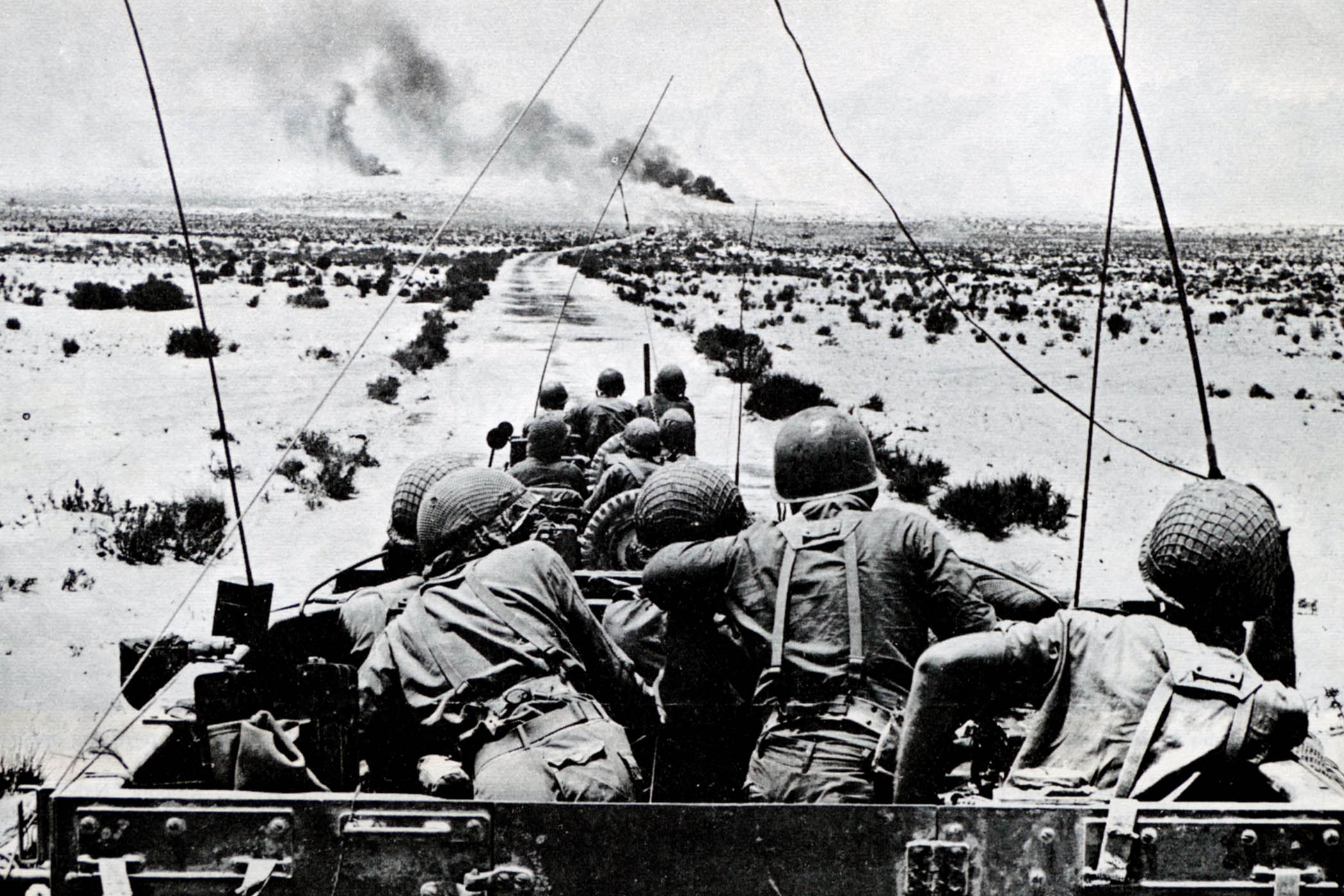

Smoke fills the sky after Israeli settlers set fire to the properties of Palestinian villagers in the West Bank village of al-Mughayyir, Saturday, April 13, 2024

Plans for a controversial settlement project that were long on hold are moving ahead. Announcing 3,400 housing units in the project called E1, the far-right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, hailed it as the death knell for Palestinian sovereignty: “The Palestinian state is being erased from the table, not by slogans but by deeds,” he said.

When Yisrael Medad moved to the West Bank in 1981, there were only 30 houses on the hill above the site of the ancient tabernacle – the central site of worship for the Israelite tribes more than a millennium before the birth of Christ.

“My wife and I decided that Jewish history is a very long chain of events and hopes and aspirations extending back to the time of Abraham and on,” he said. “A chain is only as strong as its weakest link and … we wanted to be the stronger links.”

Born in Brooklyn, Medad was part of an early wave of settlers who arrived after Israel routed Arab armies in the six-day war of 1967, seizing the whole of historical Palestine, including the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem. They were not welcome.

During 1990s peace talks, Israel agreed to transfer control of the West Bank and Gaza to a self-governing Palestinian body while negotiations over a two-state solution continued. But the Oslo accords fell apart.

More than three decades on, 3 million Palestinians still live under Israeli occupation in the West Bank. Among them are roughly half a million Israelis, including Medad, who live in 150 West Bank settlements deemed illegal under international law. The Shiloh settlement where he lives is now the site of 450 houses.

Like him, the vast majority are not involved in acts of violence against Palestinians, but a radical minority has become increasingly bold.

“When we came out here, we viewed the idea of reclaiming the land as the instrument that will bring us to a better future,” said Medad. “For them, the less Arabs we have here, that is the instrument to the realisation of their aims.”

Looking back, Medad identified Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 as a turning point in the settler movement. The supposed “disengagement” forced about 8,000 settlers to abandon their homes in the Palestinian enclave, undermining the authority of traditional settler leaders, who were seen to have betrayed Zionist ideals.

Olive trees reportedly uprooted by Israeli soldiers using a bulldozer in al-Mughayyir in August 2025

“Afterwards, all these kids began to grow up and say: ‘We know what’s best; we’re going to go out and shepherd,’” said Medad.

Young settlers went out and pitched tents on hilltops across the West Bank. Known as “hilltop youth”, they herded livestock to claim tracts of land. Today, the territory controlled by a few hundred settlers in such outposts is four times larger than the total area of more established settlements – and is rapidly expanding.

Roadsides reflect the changing face of the settlement enterprise. Adverts for housing in settlements are interspersed with giant billboards depicting an Israeli shepherd with a flock under the banner: “We salute the hilltop youth.”

The UK imposed sanctions on the hilltop youth last year over their role in an escalating campaign of violence against Palestinians. In the first half of this year, the UN documented a record number of settler attacks across the West Bank, ranging from arson and theft of livestock to physical assault and murder. In thinly populated rural areas, entire communities have been displaced. Emboldened by their gains, settlers are now encroaching on bigger villages in fertile areas such as al-Mughayyir.

Members of Israel’s traditional security establishment have raised the alarm over mounting settler violence, which has increasingly drawn in the military. In his resignation speech in July last year, Maj Gen Yehuda Fox, head of the Israel Defense Forces’s central command, with responsibility for the West Bank, lambasted settler leaders for failing to curb what he called a “nationalist crime”.

“It has sown chaos and fear in Palestinian residents who did not pose any threat,” he said.

Ronen Bar, head of Israel’s Shin Bet security agency, went further, warning in a letter to Netanyahu the following month that “Jewish terrorism” was out of control in the West Bank.

Tacit support from the police under the far-right national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, had emboldened the hilltop youth, who often used weapons distributed by the state, according to Bar. It was fuelling a cycle of violence that stretched the Israeli military, damaged the country’s reputation and was “a massive stain on Judaism and us all”. He was subsequently fired.

Palestinian properties are set on fire by Israeli settlers in al-Mughayyir in April 2023

The spiral of violence that would engulf Abu Alia and his family had been ignited when a group of settlers emerged from a new outpost near al-Mughayyir.

“Watch out – the settlers are coming!” a boy yelled from the window of a battered car as it sped away. Behind him, 10 masked men wielding sticks and wearing jeans and T-shirts were charging up the road. As the settlers advanced, Palestinian men from the surrounding villages scrambled to fend them off.

One man raced up on a quad bike. Another wearing a balaclava used a slingshot to launch a rock at the settlers, who threw rocks back. Others gathered up more rocks to throw. A call went out on a WhatsApp group for more men to come and help. Rocks flew back and forth until two army jeeps arrived, forming a buffer. But the presence of the Israeli military did not deter the settlers as they rampaged through the surrounding Palestinian farmland. Shepherds rushed their flocks to safety as the masked men broke into isolated farm buildings and set them alight.

The settlers eventually retreated, leaving the people of al-Mughayyir to clear up the damage. Volunteer fire crews doused burning buildings. Cars smouldered by the side of the road. A sheep that had become separated from its flock lurched around a pen. Settlers had stabbed it in the neck.

The Israeli military said it had responded to reports of a confrontation on the outskirts of al-Mughayyir in which four Israeli citizens were injured. Hours after the clashes, the army entered the village “to examine the incident”.

“During their activity, terrorists hurled rocks and molotov cocktails towards the forces, to which they responded with fire to remove the threat,” the military said in a statement.

Palestinians replant an olive tree reportedly uprooted by Israeli soldiers using a bulldozer in al-Mughayyir in August 2025

The next day, Abu Alia’s body was carried through the village on a stretcher, followed by a crowd of men chanting nationalist slogans. Palestinian flags flew alongside banners of the Fatah and Hamas movements.

In the last photograph he posted of himself, he stands on a roof with the lights of a village glowing in the darkness behind him: “Nothing will break us because we are prepared to lose everything,” reads the caption.

Residents hailed him as the latest in a long line of martyrs for the Palestinian cause, posting images of him with a Palestinian scarf tied around his face and posing with a gun.

His death brought the number of Palestinians killed by Israeli forces or settlers in the West Bank to more than 600 since the start of 2024. The figure, including civilians and militants, has soared since the 7 October 2023 attacks by Hamas, which prompted Israel to launch a multi-front “war on terror” reaching as far as Iran. In February in the West Bank, Israeli tanks rolled into the Jenin refugee camp for the first time in more than two decades, driving 40,000 Palestinians from their homes in the largest displacement since the war in 1967.

Over the same period, 32 Israelis – including four children and 13 members of the security forces – were killed in attacks by Palestinians or armed clashes in the West Bank, according to the UN.

In a message posted on a public WhatsApp channel before Abu Alia’s funeral, settlers were warned to stay away. Children sprinted ahead of the ambulance that carried his body the last stretch of the journey home.

Outside the family home, his father was defiant. “No matter how many they kill, time is on our side,” he said over the muffled sobs of women and children. “We won’t give up our land.”

Israeli minister of national security and far-right politician Itamar Ben-Gvir

Four days after Abu Alia was buried, an Israeli shepherd was attacked near the village. The military said a “terrorist” had shot at Israeli citizens near an outpost, lightly wounding one. Photographs from the scene showed a quad bike knocked on its side and a streak of blood beneath the ear of the victim. The gunman allegedly fled in the direction of al-Mughayyir.

The response to the attack would fall to Maj Gen Avi Bluth, who took over as head of the Israeli military’s central command last year, vowing “zero tolerance” towards violence of any kind. The appointment of Bluth, a religious Zionist who grew up in a West Bank settlement, was welcomed by settlers, who accused his predecessor of siding with Palestinians.

Briefing his men near the scene, Bluth vowed to teach the people of al-Mughayyir a lesson. “Every village and every enemy needs to know that if they carry out an attack against the residents, they will pay a heavy price,” he said in a video.

Within hours, Israeli forces had sealed off al-Mughayyir. As soldiers spread through the village, bulldozers deployed in the surrounding olive groves. One driver filmed the view from the cab of a bulldozer as it mowed down trees planted decades ago: “You sons of whores, don’t mess with me, next terror attack I’ll take down a house,” read a text on the video that was circulated on social media.

Trapped in their homes, residents secretly filmed Israeli troops moving around al-Mughayyir and shared the videos on a WhatsApp channel. In one clip, a soldier dropped a rock the size of a grapefruit on to a car windshield.

Soldiers headed to the home of Abu Alia’s family, detaining his father and several brothers. Dozens more homes were ransacked by the Israeli military. Photographs shared by residents showed upturned furniture, smashed phone screens and cupboards spilling their contents.

The Israeli military said it had detained the suspect in the attack on the shepherd and located a firearm, but the siege continued.

Addressing residents via a video on Facebook, the head of the village had a stark message: “It seems the time has come for the Israeli government and the settlers to implement their threats to displace the people of al-Mughayyir to Lebanon and Syria,” Amin Abu Alia said, urging the international community to intervene.

The Palestine Red Crescent said the Israeli military had denied entry to an ambulance crew called to help a woman in labour. Soldiers fired teargas in her direction as she attempted to leave the village on foot, the UN said.

Extremist settlers who have previously criticised the military for being too soft on Palestinians praised Bluth and urged him to go even further.

“It seems, under pressure from the settlement community, the security establishment has finally woken up,” said Elisha Yered, an unofficial spokesman for the hilltop youth, who was sanctioned by the UK last year for inciting violence against Palestinians. “This is a full-fledged terror village that needs to be wiped out.”

In a neighbouring village, stranded residents exchanged anxious messages with relatives in al-Mughayyir and checked the WhatsApp channel for updates. Ghassan Abu Alia was at work in the planning department when the Israeli military encircled the village, separating him from his wife and children. “They want to create a new reality: to clear the residents and put us in small cantons surrounded by fences,” he said.

Israeli soldiers and border police at a site where settlers burned Palestinian cars and wheatfields in al-Mughayyir in May 2023

On the fourth day of the siege, the head of the village council addressed his people again; the army had agreed to withdraw if he handed himself in to the authorities. “I will sacrifice my freedom for you,” he said in a video. “God willing, we will meet again soon”.

Residents emerged from their homes to find Stars of David, MTA and MH spray-painted on the walls: the initials refer to the football clubs Maccabi Tel Aviv and Maccabi Haifa. A banner commemorating Abu Alia’s death was torn.

In the fields around the village, residents mourned the prostrated remains of 3,100 olive trees. Some tried to replant them, vowing not to be uprooted. Two leading Israeli human rights groups demanded the military open an investigation into Bluth for war crimes over what it described as “collective punishment”.

There is a logic behind Israel’s actions. If you don’t enforce the law, you get more land

There is a logic behind Israel’s actions. If you don’t enforce the law, you get more land

Dror Etkes, Kerem Navot NGO

“For months, lawlessness in the West Bank has made war crimes and crimes against humanity part of daily life,” the Association for Civil Rights in Israel said in a letter to the army’s prosecutor. “Alarmingly, the army has begun to boast about it.”

Facing criticism, the Israeli military said it had acted out of “operational necessity” by uprooting the trees because they provided cover for the gunman. Netanyahu jumped to Bluth’s defence after a columnist in the leftwing Haaretz newspaper branded him a “general of bloodshed” and likened him to a Nazi military commander.

The state’s heavy response in al-Mughayyir only highlighted the impunity enjoyed by settlers. In the weeks leading up to the siege, settlers had shot and killed Palestinians in four separate incidents in the West Bank. None of them were prosecuted, even though three of the shootings were filmed.

“There is a logic behind it,” said Dror Etkes, a leading expert on Israeli land policy in the West Bank and the founder of non-governmental organisation Kerem Navot. “If you don’t enforce the law, you get more land.”

As the residents of al-Mughayyir attempted to pick up the pieces, Israeli authorities issued demolition orders, including to two of Abu Alia’s brothers. The head of the village council was released, but four of Abu Alia’s brothers are still detained.

Meanwhile, the bulldozers kept digging; a new road is being built to connect two outposts, tightening a noose around the village. Settlers resumed their campaign of harassment. Several videos showed them loading the broken limbs of olive trees on to trailers.

Photograph by Zain Jaafar/AFP via Getty Images. Other pictures by Nasser Nasser/ AP, Menahem Kahana/AFP via Getty Images, Majdi Mohammed/ AP