Brazil’s capital was built with democracy in mind. In 1956, after the end of authoritarian rule, the democratically elected president Juscelino Kubitschek ordered a new city to be built, and turned to the country’s leading architect, Oscar Niemeyer, a protege of Le Corbusier, to design the heart of Brasília.

Niemeyer wanted to build something distinctive that would represent the very best of the new, democratic Brazil. The centrepieces – the cathedral, presidential palace and foreign ministry – are stunning works of art and instantly recognisable. And in the 65 years since they were completed, Niemeyer’s buildings have played host to the fall and rise of Brazilian democracy again and again.

Most recently, they were the setting for Jair Bolsonaro’s violent attempt to hold on to power after he lost the 2022 election, when a mob of his supporters stormed the congress, supreme court and presidential palace. And last week, the Niemeyer-designed supreme court was where Bolsonaro, along with five military allies, was found guilty of plotting a coup and sentenced to 27 years in jail. In the words of the judges, Bolsonaro had tried to “annihilate” Brazilian democracy, which would have led to the “return of dictatorship”.

Democracy is in crisis. There are now more autocracies than liberal democracies, with almost three-quarters of the world living under authoritarian rule, according to a March report from the Varieties of Democracy Institute at the University of Gothenburg.

But the court case in Brasília reminds us that that democracy isn’t dead – and shows what can happen when democratic institutions (and those who lead them) have the courage to stick to their principles. Crucially, the case was brought swiftly, while memories of the coup attempt were still fresh and before Brazil entered another election cycle.

Compare and contrast with the case of Donald Trump, a man also accused of fomenting a mob in an attempt to overthrow a democratic election. The US justice department took almost two years to appoint a special counsel, before the supreme court – which Trump himself had stacked in his favour – first delayed the case, then granted presidential immunity. Before the case could be heard, it was election time and Trump was able to claim the charges were part of a political conspiracy to silence him.

There is an argument that, no matter when charges had been brought, Trump would have used them to his advantage. Scroll back to the days after 6 January 2021, however, and the mood was very different. The House of Representatives voted to impeach, and if the Senate had followed suit, he would have been constitutionally barred from running again.

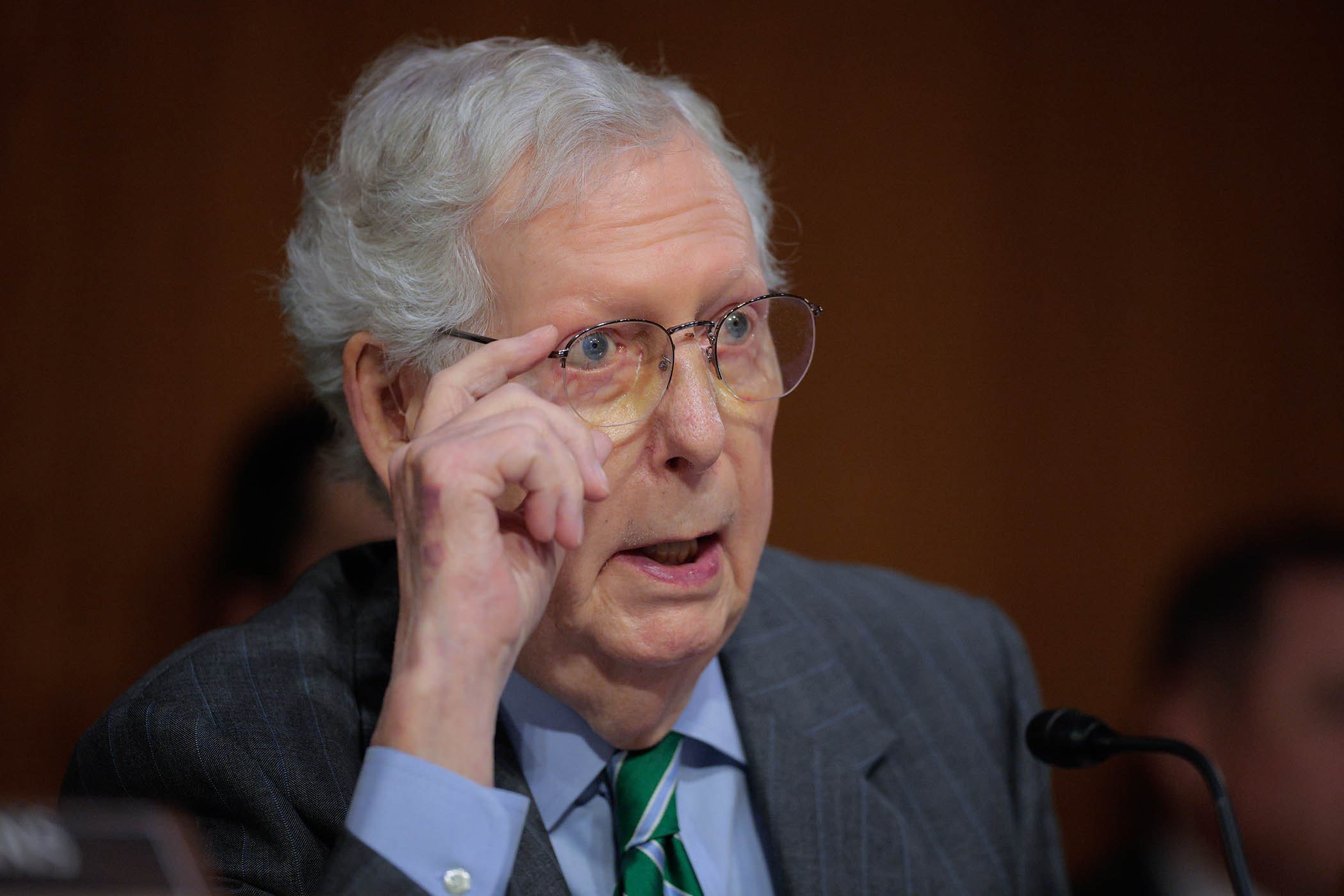

Mitch McConnell

In the aftermath of the attack on the Capitol, Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader, said: “The mob was fed lies. They were provoked by the president.” He told allies he was minded to vote for impeachment. It looked as if the Republican establishment was finally prepared to break with Trump. But McConnell delayed the vote for more than a month, by which time Trump had reasserted his party within the party. Seven Republican senators joined the Democrats in voting to impeach, but it wasn’t enough to get the necessary two-thirds majority. That was the moment Trump should have faced justice – and they blew it. (McConnell, it’s worth mentioning, voted to acquit the man he had accused of fomenting the violence.)

Related articles:

Imagine for a moment if Trump had been barred from standing again. It’s possible, of course, that another Maga candidate – maybe even another Trump – would have swept all before him in the Republican primary. But it’s also possible that a more conventional – that is, less authoritarian – candidate would have emerged as the party dealt with the damage wrought by Trump’s presidency and the 6 January insurrection.

Democracy’s next big test will come in January when Marine Le Pen’s appeal against her conviction for embezzling £2.5m of public funds will be heard in France. If it’s upheld, the far-right leader will be barred from running for presidency in 2027. Her original conviction in April was met with anguished cries from liberals, not because they believed she was innocent but because they feared it would bolster Le Pen’s National Rally party.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The danger of such muddled thinking is obvious: if would-be demagogues face no consequence for breaking the law, democracy is at risk. It is profoundly undemocratic to have one rule for them and another for us.

Brazil’s democracy is fragile. Two decades of dictatorship have been followed by 40 years of political volatility. But it showed last week that its democracy is in a healthier state than the once shining city upon a hill to its north.

Photographs by Joedson Alves/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images and Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images