Tsadik Bayou’s new flat on the edge of the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, is little more than a concrete shell. There is no flooring or plaster, and the bare walls are covered in scorch marks left by melting electrical wires.

Five people share the two rooms. Bayou’s mother and sister sleep in the only bed, while he and his two brothers bunk down on the cramped living room floor. “It’s barely fit for humans,” says the 37-year-old construction surveyor.

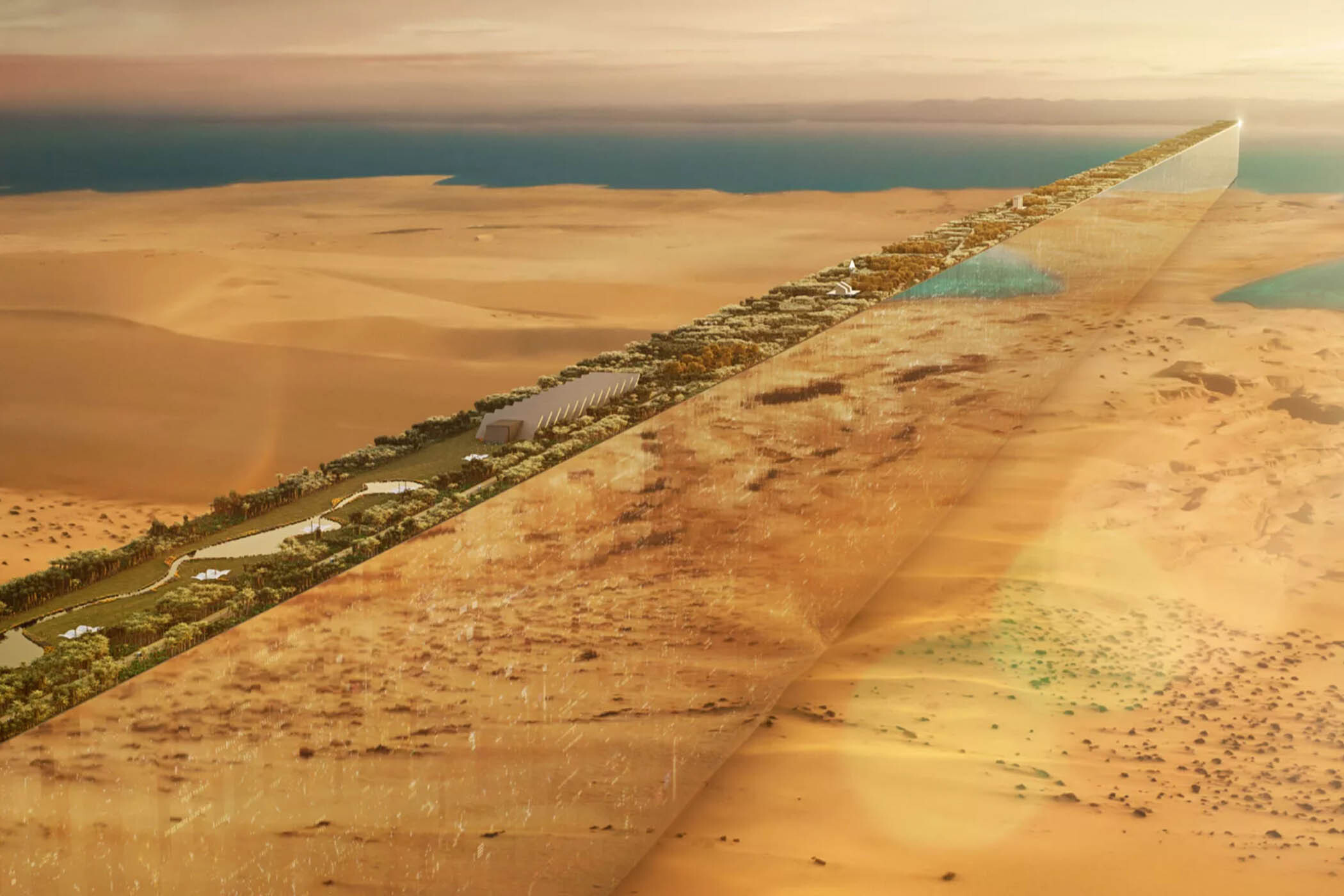

The family are among the thousands of people who have been uprooted as the prime minister, Abiy Ahmed Ali, radically reshapes Addis Ababa. As the home of the African Union, the city has long been the continent’s diplomatic capital. Now Abiy is transforming it into a modern hub, modelled on Dubai, in the hope of attracting wealthy tourists and investors, and reviving a flagging economy.

The pace of change is staggering. Over the past two years, whole neighbourhoods have been razed. The city has a new conference centre, public library and science museum, as well as a string of manicured parks. Its main avenues are lined with bike lanes, golden streetlamps and LED lights.

Perhaps the most ambitious project of all is a vast new complex in the hills overlooking Addis Ababa, rumoured to include a zoo, artificial lakes and a cable car. Abiy has said it will cost as much as £8bn. He has also started work on Africa’s biggest airport, worth £7.5bn. This in a country whose entire annual budget is about £10bn.

‘We are curing a generational mentality of darkness and creating a city of light’

‘We are curing a generational mentality of darkness and creating a city of light’

Abiy Ahmed Ali, prime minister of Ethiopia

Abiy, a devout Pentecostalist who preaches a gospel of prosperity, has approached the task of transforming the city with almost religious zeal. “We are curing a generational mentality of darkness and creating a city of light,” he said in September.

The project got the ultimate seal of international approval last month when Ethiopia was confirmed as the host of Cop32 in 2027, when delegates from nearly 200 countries will descend on the city for the UN climate meeting.

Tsadik Bayou

Few can doubt Ethiopia’s environmentalist credentials. Practically all its power comes from renewables, and last year it became the first country in the world to ban the import of combustion-engine vehicles. In September, it inaugurated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, the largest hydropower project in Africa.

Related articles:

But the breakneck pace of development in Addis Ababa has come at a cost.

‘We were in shock when we were told to leave. We assumed the officials must have made a mistake’

‘We were in shock when we were told to leave. We assumed the officials must have made a mistake’

Tsadik Bayou

Historic buildings, homes and small businesses have been razed with little consultation. Many residents received inadequate compensation or none, and several told The Observer they were given only a week to vacate homes they had lived in for decades. They were forced to leave sofas, cooking pans and other belongings behind.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Many have been relocated to half-built estates, such as the one where Bayou now lives. It is strewn with rubble and knitted together by rough, dirt roads. A fetid smell hangs over the surrounding fields, which are used as a toilet. Located on the eastern fringe of the city, it is a sight the Cop32 delegates will not see.

“We were in shock when we were told to leave,” said Bayou. “We assumed the officials must have made a mistake. It was all done in such a rush.”

He previously lived in Bela, an area close to the city centre, which he remembers fondly. “I lived there all my life,” he said. “For weddings, funerals, any occasion, we would all get together. It was a very strong bond.”

His new neighbour shares similar memories of her old home in Kazanchis, Addis Ababa’s diplomatic district. The area’s houses and informal dwellings have been swept away to make room for roads, green spaces and other developments.

‘You can’t say no once the government makes a decision. Some of my neighbours complained and were arrested’

‘You can’t say no once the government makes a decision. Some of my neighbours complained and were arrested’

Anonymous resident

“They told us we had to leave because the city needs renovating,” she said, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of being evicted from her new one-bedroom flat, which she shares with seven relatives. “We had no choice. You can’t say no once the government makes a decision. Some of my neighbours complained and were arrested.”

Spokespeople for Ethiopia’s government and Addis Ababa’s city administration did not respond to requests for comment on allegations that residents had been evicted at short notice and with little compensation.

Abiy has spoken of the need to remove poverty from areas such as Bela and Kazanchis, arguing that “beautiful sights that prompt joy and contentment” are a bedrock of modern development. This approach contrasts with that of previous leaders, who focused on eradicating poverty and ending Ethiopia’s cycle of famines while maintaining an iron grip on the country, which stifled dissent.

Some in Addis are supportive of Abiy’s programme, seeing it as vital to maintaining the city’s status as Africa’s diplomatic capital. “The developments are a net positive for Addis,” said Olansis, a young professional in the city. “A lot of people complain that old neighbourhoods have been demolished, but many of these places were complete slums of unspoken proportions. I commend the government for being brave enough to do something about it.”

Many other Ethiopians privately question the prime minister’s priorities. The country’s two largest regions, Amhara and Oromia, are gripped by rebellions that have displaced hundreds of thousands of people and dumped millions of children out of school. In some areas, kidnapping has become rampant, meaning people fear leaving Addis Ababa. And reconstruction is yet to begin in the northern region of Tigray after a devastating war in 2020-2022 that killed an estimated 600,000 people.

Meanwhile, as conflict, drought and other shocks take their toll, poverty is on the rise in the country as a whole, increasing from 38.6% in 2021 to 43% in 2025, reversing a previous downward trend. Ethiopia is also mired in a debt crisis after defaulting on repayments in 2023. The coffers are so depleted that it is unable to pay civil servants’ salaries.

‘A lot of people complain that old neighbourhoods have been demolished, but many of these places were complete slums’

‘A lot of people complain that old neighbourhoods have been demolished, but many of these places were complete slums’

Olansis, a young professional

“The city is becoming a playground while the rest of the country burns,” said an Ethiopian policy expert, who also requested anonymity for fear of reprisals. “If you come to Addis, you spend a few days driving around and seeing all the wonderful parks, cafes and walkways, and think: ‘Wow, this government is really delivering for its citizens.’ But then you drive two hours outside the capital and you realise the country is in absolute crisis on multiple fronts.

“It’s an economic model that is very vibes-based.”

Questions have also been raised about the financing of Addis Ababa’s refurbishment. Some has come from fundraising galas, while the African Development Bank is raising most of the funds for the new airport. But most residents suspect other projects are being bankrolled by Abiy’s allies in the United Arab Emirates. The president has told parliament that it should not worry about the source of the funds since it is not taxpayers' money.

An architect in Addis Ababa, who also wished to remain anonymous, said Abiy was using the city as a “political tool” to maintain his legitimacy in the capital as it collapses in other parts of the country. They added: “It’s the only place where the government has full control, so it's getting hit with all of these developments, almost as if it's making up for the whole country’s development.”

Photographs by Fred Harter for The Observer