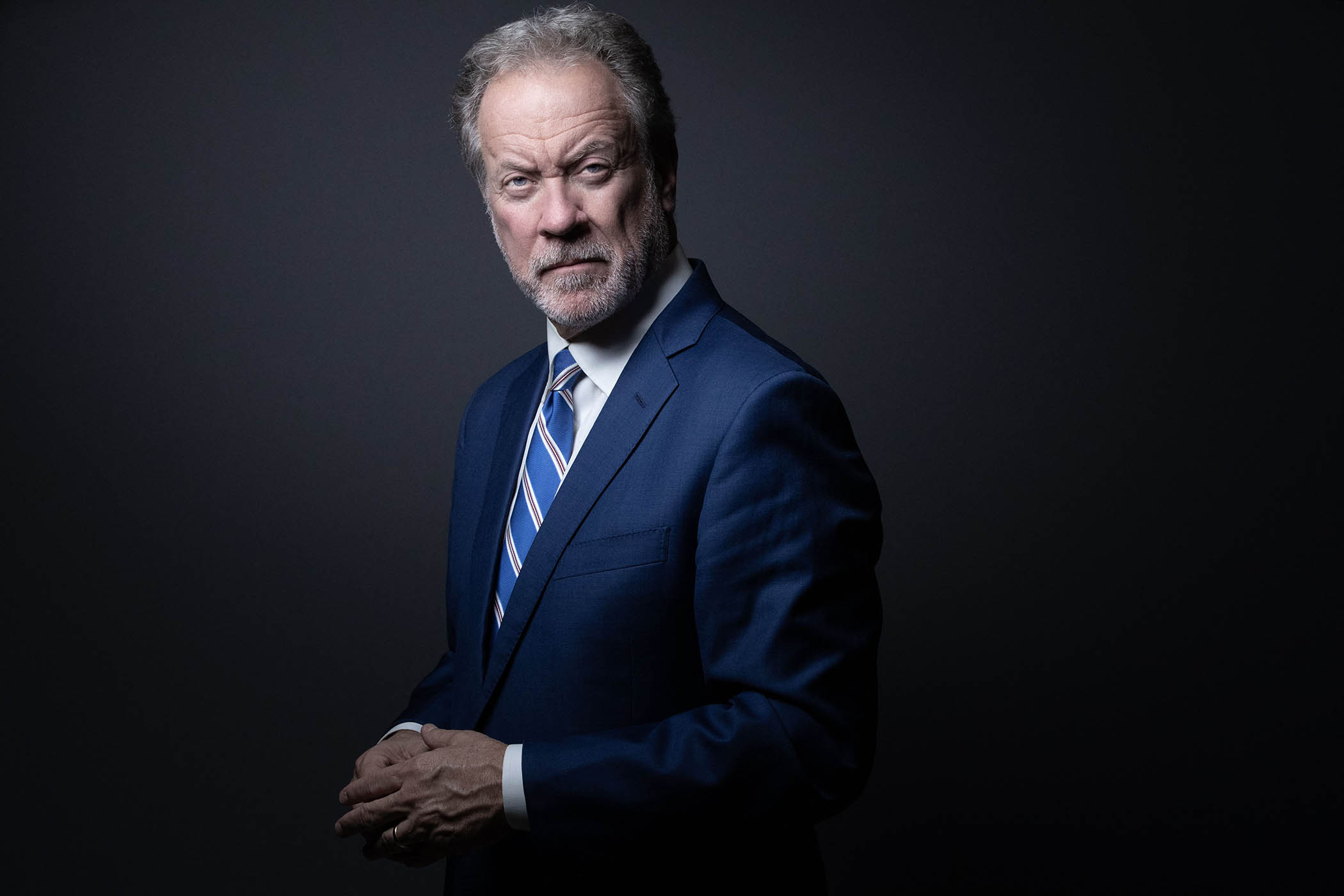

If you wanted to lobby Donald Trump not to cut aid, you’d ask David Beasley to do it. If you wanted someone to call up the leader of the Rapid Support Forces in Sudan and urge him to stop his troops killing innocent citizens in El Fasher, you’d ask David Beasley to do it. And if you wanted someone to lend much-needed credibility to your deeply controversial new aid outfit that planned to use armed contractors to deliver food in Gaza, you’d ask David Beasley to do it.

For six years Beasley, a charismatic Republican former governor of South Carolina, ran the World Food Programme. He had no background in aid, but he knew how to lobby and, crucially, how to fundraise. As he never tires of telling anyone, in his last year at WFP it raised $14bn which enabled it to feed 160m people. (By contrast, so far this year, WFP has raised somewhere between $4-5bn.)

He had a hotline to the White House and, during Trump’s first term, was a useful reminder of what American diplomacy could look like if it still cared about the rest of the world. (The WFP director, it should be pointed out, is always an American - just as the UN’s humanitarian chief is always a Brit; yes, it’s a carve-up.)

If Beasley was the most high profile representative of the old world of aid (western governments spending billions, UN agencies and NGOs delivering assistance), he is arguably now the most prominent figure trying to lead a path through the broken, frightening hellscape that is the new world of aid.

He has very few formal roles, but sees himself as a fixer and persuader. When we meet he has spent the day at the One Young World Summit in Munich, speaking to 2,000 young delegates from around the world, but in between he’s been on the phone trying to help get aid into El Fasher, the city in Sudan’s western Darfur region taken over just a day earlier by the RSF.

A Palestinian boy carries a bag of food from a distribution point run by the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation

“We’ve been trying to get supplies in, pressuring both sides, meeting with everyone involved. I know Burhan, Hemedti, all these guys,” he says, referring to the leaders of the Sudanese Armed Forces and the RSF.

The very concept of international humanitarian aid has taken a battering over the past nine months. Trump, with the help of Elon Musk, shut down USAid and its $40bn budget. Other western governments followed, including Germany and the UK, which cut its funding from 0.5% of GDP to 0.3% – a real-terms cut of about £6bn.

When the US shut down USAid, the secretary of state, Marco Rubio, claimed no one had died due to the cuts. “When children don’t get food, they die. That’s not complicated,” said Beasley. Do people in Washington understand that? “No. To say that children aren’t dying… you’re kidding me.”

He is, like so many leaders, loth to criticise Trump himself. When aid cuts were floated in his first term, Beasley claims he led the charge to prevent them. But this time around, he says, “I don’t think anyone is inside the White House making the case to him.”

Getting food to hungry people is, for him, a simple idea that is both morally and politically vital. “Food insecurity in the Sahel is skyrocketing, which means famine-like conditions, destabilisation, more recruitment by Isis and al-Qaida, and the migration that this could result in [over] the next 12 to 18 months. Families aren’t getting the food and Isis and al-Qaida are doing their best to recruit, using food and medicines.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He may not lead the WFP any more – though he hasn’t stopped referring to them as “we” – but Beasley still hits the phones and travels the world, lobbying governments to spend more on aid. “ ‘We’ is just all your friends and networks over the years, from inside the White House to the highest levels of Saudi Arabia, UAE, friends in the UN, friends on all sides of all the equations.”

None of this is particularly surprising. But what makes Beasley interesting is his willingness – up to a point – to engage with a controversial new range of actors who are trying to deliver aid outside of the formal system, and without necessarily always adhering to the traditional humanitarian principles.

He is an adviser to Fogbow, a US company that claims it can deliver aid quicker – and into more dangerous areas – than traditional humanitarian organisations. An investigation by Katharine Houreld in the Washington Post raised concerns about Fogbow’s actions in South Sudan, where they had helped the South Sudanese government deliver aid to an area that it had previously bombed. Frightened civilians who had fled were faced with the choice of going without food or returning to the area the government had attacked. Martin Griffiths, the former UN humanitarian chief, described it as “a weaponisation of aid… You cannot use aid as a lure.”

‘There are places you can’t go in the way you want to. It’s war zones and warlords. It ain’t always easy’

‘There are places you can’t go in the way you want to. It’s war zones and warlords. It ain’t always easy’

David Beasley

Beasley argues that Fogbow is trying to do its best in parts of the world where compromises sometimes have to be made. “There are some places where you can’t go in the way you want to go in, but you’ve got to figure out a way to at least minimise the risk of [loss of] integrity, and minimise the risk of diversion of aid, or being manipulated by one side or the other. It’s not like you're talking about delivering food on Saturday afternoon in New York City. This is about war zones and warlords and it ain’t always easy.”

One group where he drew the line, though, was the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), a US and Israeli-backed private initiative to bypass the UN and deliver aid in Gaza. A security company was hired to provide armed contractors to secure the distribution points. Within two months of its launch, 859 Palestinians were shot in proximity to GHF’s four distribution centres across Gaza, according to the UN.

Before GHF launched in May, he was reported by Axios to be under consideration to lead it. He chose not to, but has refrained from commenting, frustrating many ex-colleagues alarmed that the former head of WFP didn’t distance himself from an organisation accused of complicity in the killing of almost a thousand people.

He said he held “extensive discussions” but the plan had already been developed: four fixed distribution points, which meant people would have to walk for miles to reach them; and armed security, something no aid organisation would ever agree to.

He had immediate concerns. “I just didn't have the confidence and the comfort that I was going to be given the authority and the flexibility to be empowered to do what I really knew needed to be done.” He worried he wasn’t being told everything - “the last thing you want is [them] misleading me” and that there was little chance of achieving the only goal that mattered to him: “reaching every hungry child inside Gaza”.

The killings, he said, were “heartbreaking”, but he’s careful with criticism. “I would have been in the middle of Gaza, beating the hell out of everybody on all sides. I’m a big friend of Israel, but when it comes to innocent children… To me, it’s simple. You do what’s right for the innocent children.”

Some in the aid world are wary of Beasley’s informal role and what it says about the future of humanitarianism. Beasley, without a job but with a mission, will keep hitting the phones and ignoring the criticism. “It’s just friends, behind the scenes, trying to get some good accomplished.”

Photograph by JOEL SAGET/AFP via Getty Images, EYAD BABA/AFP via Getty Images