The Casa Grande del Pueblo – the Great House of the People – towers over the old presidential palace in La Paz, Bolivia’s political capital.

Decorated with Indigenous icons, the colossal glass structure was built in 2018 as a triumphant symbol of the country’s reinvention and shining future under the ruling Movimiento al Socialismo (Mas) party.

But just a year later, the Mas project began to crack. And now it is on the brink of total collapse.

On Sunday, Bolivia faces its most open election in 20 years. Not only does the country seem set to swing to the right but Mas, one of the continent’s most successful leftwing parties, may disappear entirely.

‘The right is ascendant. They are not just talking about cuts – they’re talking about removing rights’

‘The right is ascendant. They are not just talking about cuts – they’re talking about removing rights’

Carlos Arze Vargas, Cedla thinktank

“The right is ascendant,” said Carlos Arze Vargas of Cedla, a thinktank. “There’s a quite conservative and even retrograde atmosphere.” Some parts of the right, he added, “are not just talking about cuts – they’re talking about removing rights.”

Polls, while not reliable, point towards an October runoff between Samuel Doria Medina, 66, a centre-right tycoon, and Jorge “Tuto” Quiroga, 65, a rightwing former president, who each have about 20% to 25% of voting intention in a field of eight candidates. It is the fourth presidential run for both.

The Mas candidate, Eduardo del Castillo, 36, is polling at under 2% – which would translate to not only being wiped from parliament, but the party losing its legal status.

It is an extraordinary collapse for a party that won every election since 2005 with more than 50% of the vote in the first round, as it delivered material progress and political representation for Indigenous people and the working class.

Led by Evo Morales, the charismatic coca farmer turned president, Mas forced contract renegotiations with the companies extracting Bolivia’s natural gas and used the windfall to boost social spending. The country adopted a new constitution with an emphasis on Indigenous rights.

Mas became hegemonic, strengthening its control over Bolivian politics – and its courts. Meanwhile, Morales became a feature of the “pink tide” of leftist governments in Latin America, alongside Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Perhaps the first crack appeared in 2016, when Morales lost a referendum on whether he could run for an unconstitutional third consecutive term in 2019. Nonetheless, a court ruling said it would be against his human rights to stop him. After a disputed election led to mass protests, the army “suggested” Morales resign. He did and went into exile.

Jeanine Áñez, a conservative senator, became interim president in what Mas views as a coup. Áñez promised to hold new elections, but her government set about undoing Mas’s legacy. Áñez moved back into the old presidential palace – with a giant bible in tow.

When the rerun election was finally held a year later, Luis Arce, Morales’s former finance minister, won with 55% of the vote. Morales returned from exile – but it soon became clear both men wanted to lead Mas into the 2025 elections. After years of bitter infighting, neither is on the ballot paper. An economic crisis led Arce to withdraw his candidacy. Meanwhile, Morales was excluded by a court ruling on term limits.

The only hope for the left is Andrónico Rodríguez, the 36-year-old president of the senate, who is polling at under 10%. Rodríguez was part of Mas and from the same coca farmers’ union as Morales, but when he launched his candidacy, Morales branded him a traitor and called on Bolivians to spoil their ballots. Rodríguez is now standing as a candidate for a new leftwing alliance.

As the hardcore of the Mas vote splits between factions, while many other voters will simply abandon it. Even if the party scrapes above 3% and therefore clings onto its legal status, it will be a husk. Meanwhile, the right is anticipating a legitimate return to power after 20 years in the wilderness.

Whoever wins will face a grim economic situation. Mas’s long-running economic mismanagement caught up with it in March 2023, when the government essentially ran out of foreign exchange. It now struggles to import fuel, while inflation this year is already at 17%.

The economy has been the overriding issue of the campaign. Both Medina and Quiroga have promised to liberalise the economy and cut public spending.

But some fear a rightwing government may go much further than that, undoing the legacy of Mas wholesale.

“I don’t know if Medina and Quiroga see how the country has changed,” said Pablo Mamani, a sociologist from one of Bolivia's largest Indigenous peoples, the Aymara. “We’re not in 2005 – we’re in 2025. The country is not the same. The people are not the same: they think differently.”

Roughly 40% of Bolivians self-identify as Indigenous. And they now expect to be represented and treated as equals, said Mamani. “Parliament is no longer a sacred place for certain social groups, but a place for them too.”

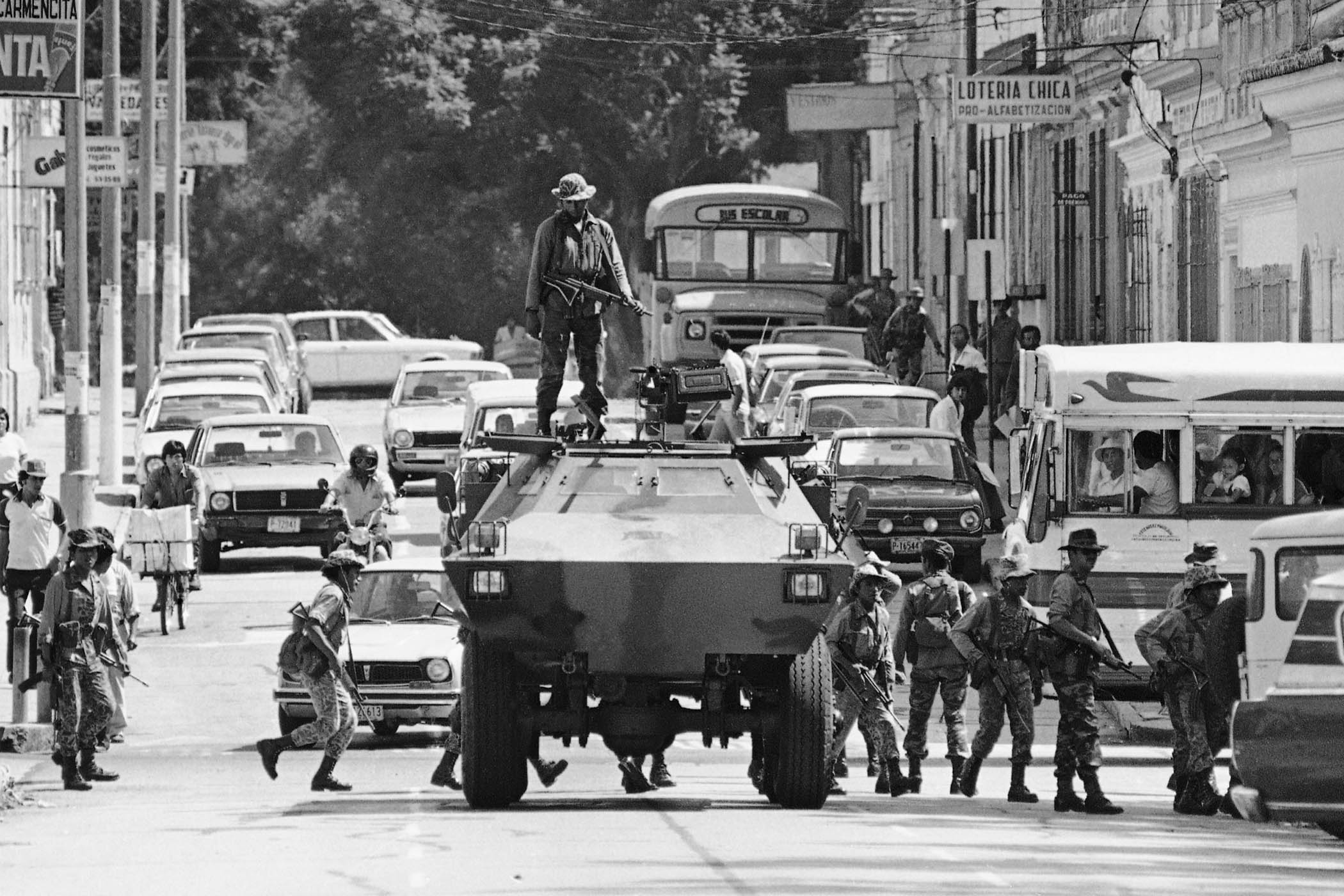

Photograph by Lucas Aguayo/Getty Images