In April 2024, Bumble announced a quiet but consequential change to its core product: women no longer had to be the ones to start conversations on the dating app. For a decade, “make the first move” had been the brand’s motto, promising to put women in control of who they spoke to, reduce harassment and give them a sense of agency in the overwhelming deluge of online dating.

Publicly, the company framed the shift as a response to user fatigue. Women were feeling “exhaustion with the current online dating experience”, its then chief executive, Lidiane Jones, said at the time, adding that the update was about giving users “more choice”.

Privately, a different story was playing out. Three people with direct knowledge of internal discussions say the change was driven by mounting legal pressure from men’s rights activists and law firms in the US. Between June and August 2023 alone, Bumble received more than 20,000 legal threats alleging that the app discriminated against men by not allowing them to make the first move.

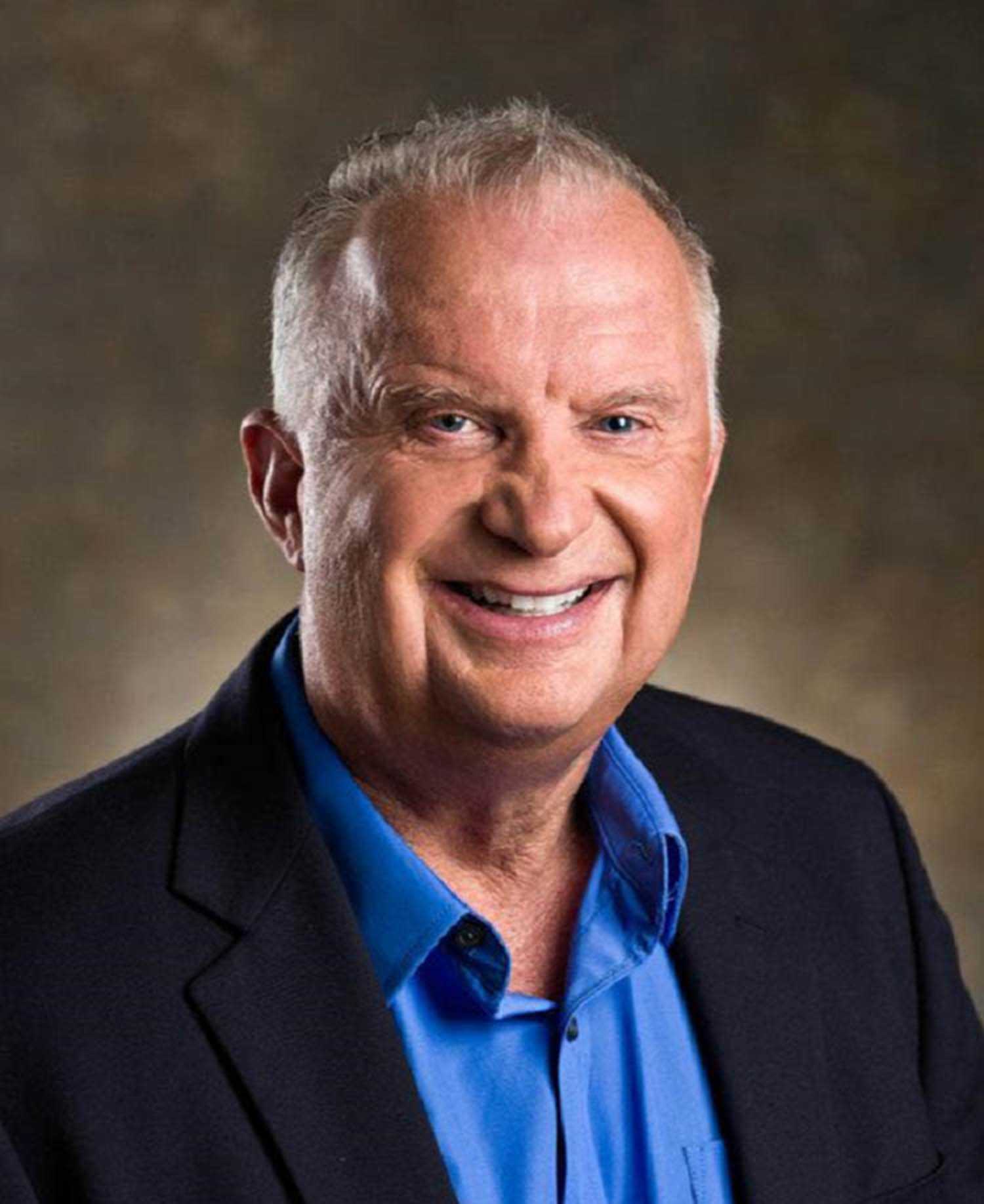

Today, the company is still battling a lawsuit that argues that Bumble’s true motive has “always been about exploiting sexual stereotypes for profit”. The case was brought by Alfred Rava, a lawyer who is hailed as the “man of the decade” on Reddit’s MensRights forum. He has filed hundreds of lawsuits challenging gender-based policies and promotions in California, including ladies’ nights at bars, Mother’s Day giveaways at baseball games and women-only networking events. Filed in 2024, his Bumble lawsuit argues that the company “portrays females as perpetual victims needing special emotional and psychological protection”, and that it stereotypes men as “rude, sexually-forward ogres”. Bumble has moved to dismiss the case.

Former employees say that, by changing its core product, Bumble has capitulated to the demands of men’s rights activists at a moment when it can least afford to do so. Since going public in February 2021, the company’s share price has fallen by about 90%, wiping out much of the value created by an initial public offering (IPO) that briefly made its founder, Whitney Wolfe Herd, the world’s youngest self-made female billionaire.

As the pandemic-era online dating boom has waned, people looking for love have grown tired of swiping through endless profiles. Bumble has lost ground to rivals such as Hinge, which promises to facilitate meaningful matches. “We are in a decline from a numbers standpoint,” Wolfe Herd told staffers in August. “Dating apps are feeling like a thing of the past.”

When Wolfe Herd returned to the company as chief executive in March, she did so under intense pressure from shareholders and a legal campaign challenging the app’s founding principle. Former employees say her attempts to restructure the business have created turmoil at Bumble’s UK and European offices, as the company struggles to reinvent itself without the feminist framing that once set it apart. What happens when a company built on women-first values decides that it can no longer afford to protect them?

Whitney Wolfe Herd attends Bumble Presents: Empowering Connections in Austin, Texas, in 2018.

Bumble was founded in 2014, the year of the girlboss. The term, popularised by a memoir of the same name, came to define an era of corporate feminism when “the future is female” merch was ubiquitous. That year, Beyoncé performed at the MTV VMA awards in front of a giant, glowing “FEMINIST” sign, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s book of essays, We Should All Be Feminists, became a bestseller. Wolfe Herd, a rare female founder in Silicon Valley, was held up as a symbol for a new era.

Related articles:

She had already helped usher in the dating app revolution in 2012 as a cofounder of Tinder, before suing the company two years later, alleging sexual harassment and gender discrimination. Later in 2014, she partnered with the Russian entrepreneur Andrey Andreev, whose dating app Badoo had found success outside the US but struggled to break into the American market. Built on Badoo’s existing infrastructure, Bumble was based on a simple idea: women would make the first move. Inspired by Wolfe Herd’s experience at Tinder, the hope was that the app would give women more agency in the chaotic world of online dating, and help them avoid harassment online. She became the company’s chief executive, and the app took off instantly, gaining more than 1 million users in its first year.

After a 2019 Forbes investigation exposed a misogynistic workplace culture at Badoo’s London headquarters, Andreev sold his majority stake to the private equity firm Blackstone, and Wolfe Herd was promoted to chief executive of the wider Bumble Group.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

She took the company public in February 2021, ringing the Nasdaq bell wearing a bright yellow Stella McCartney power suit to match Bumble’s beehive logo, carrying her one-year-old son on her hip. Just three of the 550 companies that went public in the US that year were founded by women, including Bumble, and the moment was hailed as a feminist breakthrough. Earlier this year, Wolfe Herd’s rise was dramatised in the Hollywood biopic Swiped, starring Lily James.

‘Wasn’t this app supposed to empower women to date on their terms?’

‘Wasn’t this app supposed to empower women to date on their terms?’

Jordan Emanuel, actor and model

Behind the scenes, however, the company had been battling a 2018 lawsuit brought by a Californian man, Kirilose Mansour, who alleged that Bumble’s “women message first” rule amounted to gender discrimination under the state’s Unruh Civil Rights Act. Little is known about Mansour beyond what appears in the court filings, and his lawyers did not respond to The Observer’s requests for comment. But the case became a cause célèbre in men’s-rights corners of the internet.

Bumble denied wrongdoing but quietly settled in 2021, three months after its IPO, creating a $3m settlement fund and agreeing to introduce a product update that allowed men to signal interest in other users with emojis. As part of the agreement, both Mansour and Bumble were barred from talking about the case publicly.

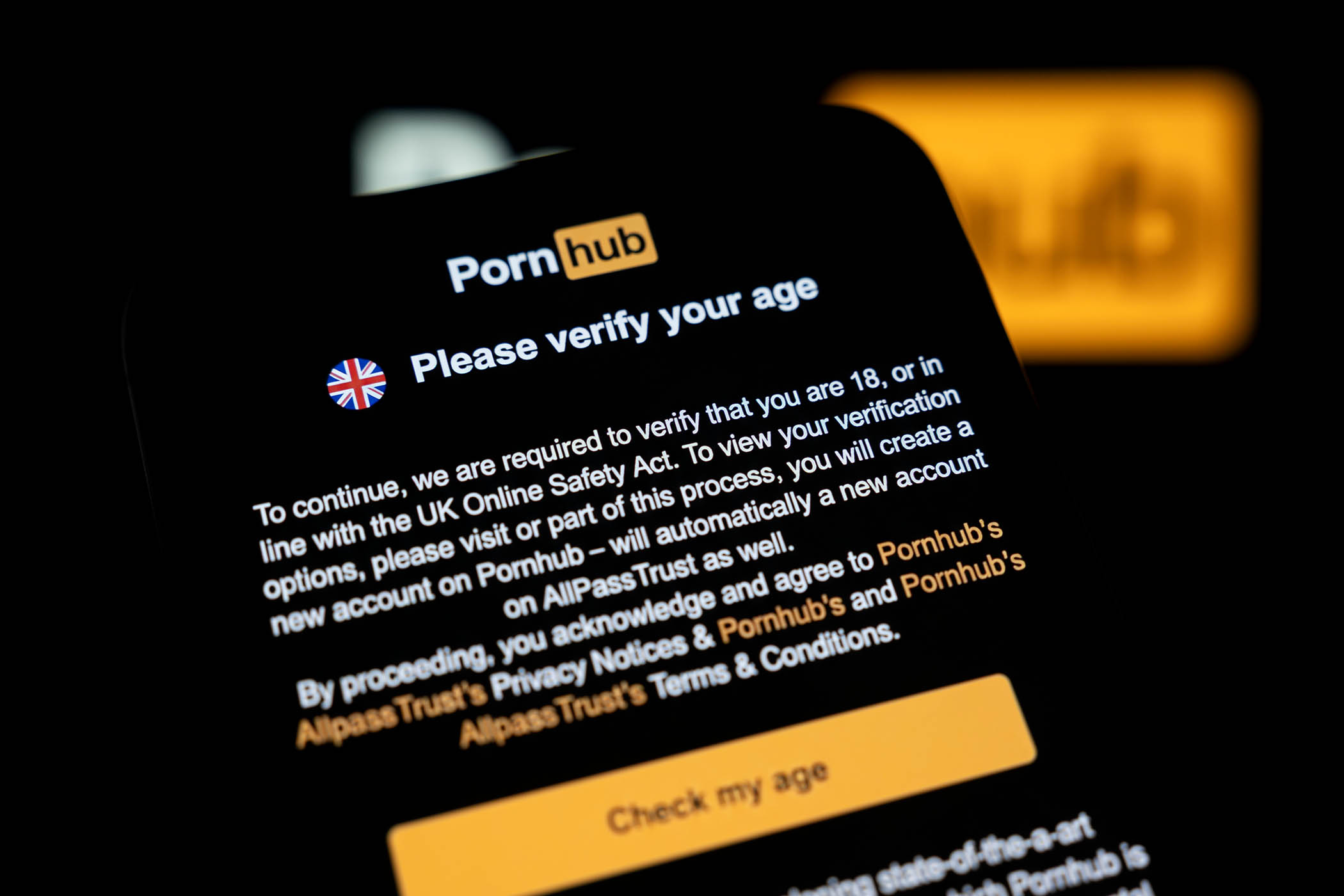

That failed to stem further litigation, and 2023 became a particularly challenging year for the company. Other men brought the same kind of complaint under the same California civil-rights law used in the Mansour case. In 2023, Bumble received a wave of more than 20,000 legal demands from law firms including Los Angeles-based Zimmerman Reed LLP. These cases were filed through a tactic known as mass arbitration, whereby thousands of near-identical claims land at once, and executives believed they were motivated by profit-seeking, as law firms typically receive a share of any settlement. In its 2023 annual report, Bumble estimated that the proceedings could cost the company $65.8m in legal fees.

According to people inside Bumble, the growing legal exposure prompted the company to begin preparing “opening moves”, a feature that allowed women to write prompts that men could respond to, watering down the “women message first” concept. Several said that California, where the legal threats were taking place, was simply too large a market to lose.

The stakes could hardly have been higher. Dating app user numbers reached all-time highs during the pandemic, but in 2023 many began reporting burnout. A Pew Research report found that women felt inundated by the number of messages they received, with several of them reporting unwanted sexual content. Men said they felt ignored and demoralised.

Users were also frustrated as apps, including Bumble, placed basic functions behind paywalls, including seeing which users had “liked” them. This fed a sense that the platforms were withholding compatible partners. Between 2023 and 2024, Tinder lost over half a million users in the UK alone, while Hinge lost 131,000.

Bumble lost 368,000 UK users that year, and had begun losing money. After peaking at a valuation of more than $13bn during the pandemic, the company was worth a seventh of that – about $2bn – by September 2023.

Lawyer Alfred Rava.

Wolfe Herd stepped down as CEO in January 2024, framing the change as a planned leadership succession for Bumble’s “next chapter of growth”. She became executive chair and was replaced by Jones, a former Slack executive, who oversaw the rollout of “opening moves”.

The feature was rolled into a broader rebrand intended to address dating-app fatigue. Bumble launched a US billboard campaign with slogans such as “You know full well a vow of celibacy is not the answer” and “Thou shalt not give up on dating and become a nun”.

The backlash was immediate. “In a world fighting for respect and autonomy over our bodies, it’s appalling to see a dating platform undermine women's choices,” the model and actor Jordan Emanuel wrote on X. “Wasn’t this app supposed to empower women to date on their terms?”

Bumble quickly pulled the campaign and issued an apology, and any debate over what “opening moves” could mean for the brand and its feminist values was eclipsed.

It was a bruising start to a brief and turbulent tenure for Jones. During her short time at the helm, she replaced almost the entire C-suite and oversaw a round of layoffs affecting about 30% of staff.

By the August 2024 earnings call, Jones acknowledged that the relaunch “was not going to plan”. Between the third quarter of 2024 and the third quarter of 2025, Bumble lost a fifth of its paying users, or nearly 700,000 people. Meanwhile Hinge, with its strapline “designed to be deleted”, had started growing its global userbase, and posting double-digit revenue gains.

‘I was very, very disappointed after that meeting. That was not the Whitney that I knew’

‘I was very, very disappointed after that meeting. That was not the Whitney that I knew’

European member of staff

Several employees say the problems at Bumble ran deeper. Because of the company’s historical partnership with Badoo, the app still relies on a legacy technology stack first built 20 years ago, including an in-house payments platform and physical servers that are maintained by Bumble staff. Most modern consumer tech companies rely on third-party infrastructure, and former employees describe Bumble’s approach as unusually costly and cumbersome. “They were spending so much resource just fixing stuff,” said one. Another called the approach “insane”.

Sources say that Bumble’s leadership resisted attempts to modernise the tech stack over the years, partly because the Badoo engineers associated with the original system were protective of it, leading to internal friction. When Jones took over, she introduced a series of AI features that she hoped would help revive the company’s share price, while longstanding infrastructure problems went unaddressed.

After Jones resigned as chief executive, citing “personal reasons”, Wolfe Herd returned to the post in March, saying she felt “energised and fully committed to Bumble’s success”. Former employees say she came back changed. “She seemed to have a very different attitude. It was much more ‘I am who I am and I don't care if you don't like me’,” said a former staffer. “I think she must have had some kind of personal epiphany.”

That epiphany may have been sparked by her friendship with Brian Chesky, founder of the tech company Airbnb. During Wolfe Herd’s time away, Chesky gave a viral interview in which he described a new leadership style he called “founder mode”: the idea that, when a company is faltering, the founder should get deeply involved in the weeds of the business, personally driving day-to-day decisions.

Wolfe Herd ordered a complete rebuild of Bumble’s underlying technology, an internal project dubbed “Bumble 2.0”. This involved “throwing away” the existing app and rebuilding another from scratch, sources say. In August, she initiated a second round of layoffs, affecting another 30% of staff in the UK and Barcelona, in an attempt to shift the company’s “centre of gravity” to the US, where leadership is based. “What I saw in there was coaching from Brian to be like, ‘No, Whitney, this is your company. Go ‘founder mode’ and take care of it’,” says a source close to Wolfe Herd.

Several former employees say the turnaround has been fraught. According to four sources, at least 25 UK-based employees were dismissed without warning in August for watching pornography on their work laptops, in violation of company policy. Sources acknowledged that individual dismissals for such conduct may be justified, but Anton Rusakov, formerly a senior software developer at Bumble and one of the people affected, says the firings felt like a “broad, coordinated action”.

Rusakov, who worked on Bumble’s trust and safety team, says that he has not intentionally watched pornography on his work laptop since the company introduced no-porn policies in early 2025. He says a number of escorting websites were flagged in his case: “That, in itself, isn’t surprising – part of our job was dealing with escort-related abuse on the platform.” He was struck by the timing of the firings, which coincided with mass layoffs elsewhere in the business “through formal redundancy processes, with generous severance packages”. Other sources speculated that the terminations were used to meet headcount-reduction targets while limiting severance costs.

A source close to the company said that the allegations are brought by disgruntled former employees and there is no evidence that the dismissals were unlawful. Bumble did not wish to respond to any specific requests for comment. Rusakov and others will be taking the matter to an employment tribunal next year.

At an all-hands meeting shortly after the restructuring was announced, Wolfe Herd criticised staff for “freaking out” about layoffs, telling employees they needed to “grow up”. “I was very, very disappointed after that meeting,” said a long-time European staffer. “That was not the Whitney that I knew.”

A decade after the dawn of the girlboss, Bumble is navigating a very different cultural landscape, where feminism is a harder sell. Silicon Valley founders are publicly lamenting that corporations have been “neutered”. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg called for more “masculine energy” in leadership earlier this year.

Alfred Rava, the men’s rights lawyer at the centre of Bumble’s latest lawsuit, is seeking a court order that would force the company to allow men to initiate conversations with women directly, not just through “opening moves”, alongside damages of $4,000 for every straight woman in California who, he argues, visited the app but chose not to join because of its women-first rule.

Inside the company, the litigation has not been openly discussed with junior staffers, even as its consequences become harder to ignore. As Bumble has continued to dilute its women-first messaging, many former employees say leadership has lost its organising principle. For a company built on the promise that woman-first design could shift power dynamics, the retreat has been costly.

But maybe it is too late for change: “If you ask members of staff at Bumble what the best dating app is, they’ll say Hinge,” says one former staffer. “But they’ll also tell you they don’t like dating apps, because the whole model seems very flawed.”

Photographs by David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty, Vivien Killilea/Getty Images for Bumble, National Coalition for Men