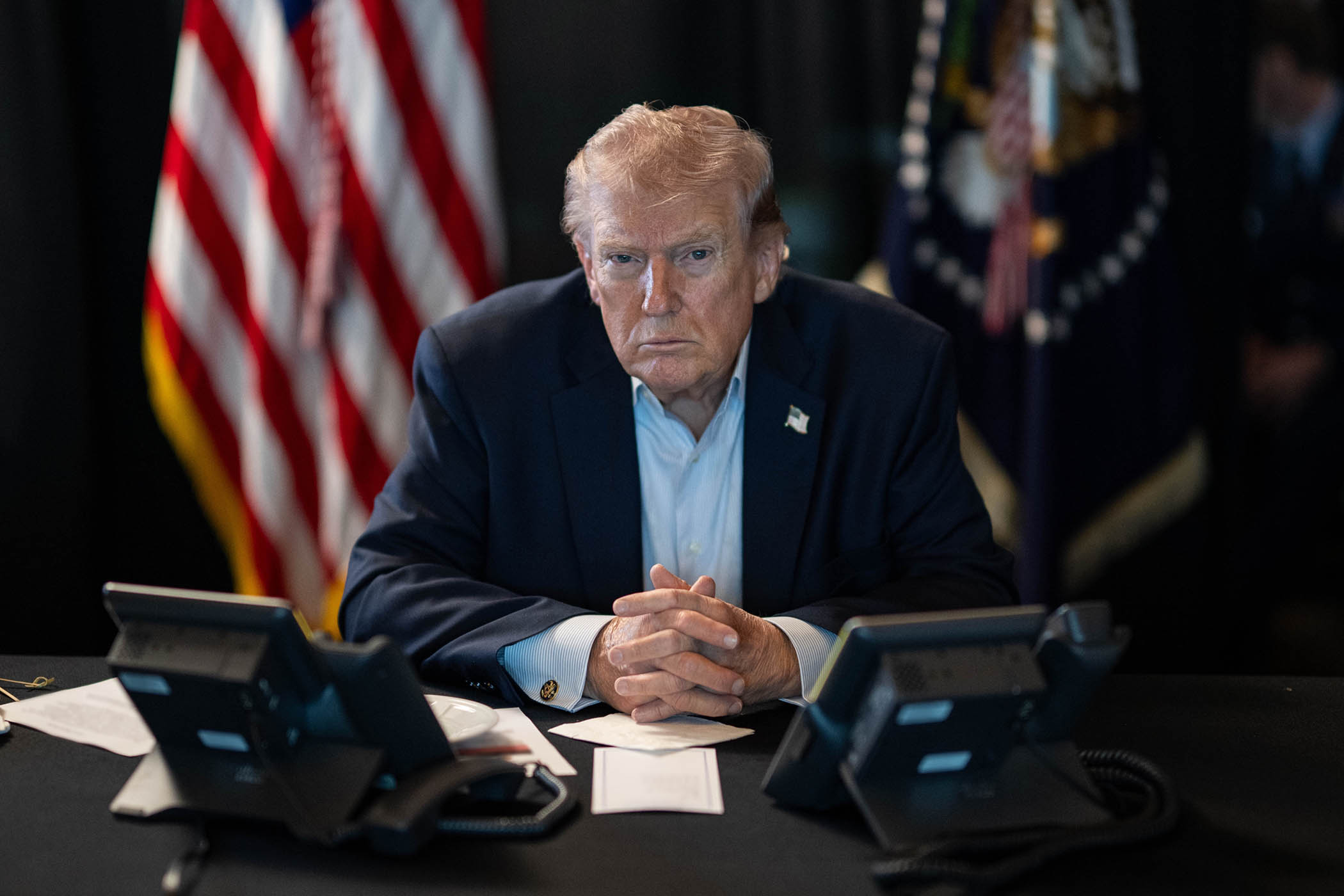

Look at the faces. You cannot. In Minnesota last week, federal immigration agents from ICE moved through residential streets with neck gaiters covering mouths and noses. They wore civilian hoodies under military-grade body armour and tactical vests carrying large “police” patches high on the chest. ICE identifiers appeared smaller, inconsistently placed, and sometimes absent altogether. On one sweatshirt, Carhartt runs down the sleeve, a civilian brand that stays legible even as institutional identification breaks down.

No individual names were visible. What should function as a uniform does not.

Uniforms exist to make authority legible across policing, the military and even private security. They clarify who is acting, under what authority, and within what limits. This legibility is not decorative; it is operational. Historically, police uniforms were designed to look civilian rather than military, precisely to signal restraint and accountability. The uniform was reassuring because it was predictable.

The clothing of an ICE agent reverses that logic. Instead of consistency, there is personalised kit. Civilian hoodies and work trousers sit beneath armour and helmets. The most prominent word is “police”, while the agency name is secondary. Force is immediately visible, but responsibility is not.

This is not accidental. It reflects an enforcement culture that prioritises mobility and tactical opacity over public recognisability. ICE was formed as a post-9/11 federal agency built for rapid deployment and flexible operations. Its clothing follows that structure. Without a standardised uniform, visibility becomes adjustable. What looks inconsistent is, in practice, a system that lets agents modulate visibility.

Clothing does more than signal power – it regulates behaviour. Uniforms manage encounters by setting expectations on both sides. Predictability reduces friction – you know who you are dealing with and where their authority begins and ends. When that predictability breaks down, the public’s experience of power changes. Uncertainty replaces clarity. Interpretation replaces recognition.

Modularity is central to how this system functions. Patches can be swapped; credentials can be clipped on or off; privately purchased gear sits alongside issued equipment. Identification becomes optional rather than inherent. Authority is no longer carried by a uniform that unifies a group; instead, it is worn individually, moment by moment, by whoever is inside the equipment. As a result, the institution becomes harder to see, while the operator becomes easier to fear and harder to name.

What these photographs from Minnesota record is not simply an enforcement operation. They show the breakdown of a visual contract between state and citizen. The shift from uniform to kit marks a deeper transformation. Power operates without the visual infrastructure that once made it accountable in real time.

When uniform functions properly, it stabilises boundaries. It allows power to be recognised and therefore questioned. In Minnesota, the clothing does none of that. It conceals as much as it asserts. The garments do not merely accompany enforcement – they structure it. These clothes do not fail by accident. They reveal a system that no longer wants to be clearly seen.

Andrew Groves is a professor of fashion design at the University of Westminster

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photograph by Victor J Blue/Bloomberg via Getty Images