It is known in Whitehall as the “chicken nugget debacle”. An Albanian criminal had supposedly avoided deportation because his son disliked foreign chicken nuggets.

Kemi Badenoch cited the widely reported case as an example of how the European convention on human rights (ECHR) “is weaponised by those who wish to erode our national identity and border security”. Nigel Farage said: “You read this stuff and you just want to cry.”

Except it never happened. There was no ruling that the foreign offender should be allowed to stay in Britain because his child was a picky eater. An immigration tribunal did initially decide that it would be “unduly harsh” for the boy to be sent to Albania because of his special educational needs, but this judgment was later overturned. A more senior judge rejected the man’s appeal and made absolutely clear that an aversion to chicken nuggets should never be enough to prevent deportation.

‘Withdrawing from the ECHR would have little bearing on stopping asylum seekers from coming’

‘Withdrawing from the ECHR would have little bearing on stopping asylum seekers from coming’

Prof Francesca Klug

This was not an isolated case. There was the Iranian criminal “spared deportation so he can cut his son’s hair”, the mass murderer who claimed that having access to hardcore porn was his human right and the Afghan migrant who could not be extradited to Belgium “because of mosquitoes” in the prison.

The political debate around human rights law is shot through with myths and misinformation, going back to former prime minister Theresa May’s suggestion in 2011 that an illegal immigrant could not be deported because “he had a pet cat”. In fact, the critical factor was his long-term partner.

The ECHR is held up by politicians on the left and the right as the block on everything from tackling the small boats crisis to deporting foreign criminals. But a recent report by the University of Oxford’s Bonavero Institute found that only 0.73% of foreign national offenders had successfully appealed against deportation on human rights grounds.

The number of successful appeals based on human rights is tiny as a proportion of the number of foreign criminals who are deported from the UK each year – around 3.5%, and just 2.5% when looking at appeals on private and family life grounds. The ECHR in Strasbourg, which interprets the convention, has ruled against the UK only three times in the past 45 years in cases relating to immigration rules.

The ECHR, drafted in the aftermath of the second world war mainly by British lawyers and signed in 1950, protects fundamental rights including freedom from torture, free speech, liberty and family life. The Human Rights Act, which embeds the ECHR in UK law, has helped secure justice for the families of those killed in the Hillsborough disaster and uphold the rights of disabled people and care home residents during the pandemic.

Related articles:

Keir Starmer, pictured at his graduation, long considered the ECHR his ‘lode star’, says his biographer

Now, however, the convention has become a defining dividing line at Westminster – a test of ideological purity on the right and a way of demonstrating radicalism on the left. For Eurosceptics, withdrawing from a treaty overseen by a Strasbourg court is unfinished business after Brexit. For Labour MPs with “red wall” constituencies in the north of England and the Midlands, hostility to the ECHR is a way of signalling intent to deal with illegal immigration.

The issue is set to dominate the party political conference season – which kicks off this week with the Liberal Democrats gathering in Bournemouth – as Labour and the Conservatives attempt to see off the threat from Reform UK. Farage has promised that if he becomes prime minister, the “first thing” he will do is “get rid of the ECHR”. Last week Richard Tice, Reform’s deputy leader, pledged to set up an immigration “department of believers” staffed by civil servants who favour severing links with the convention.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Senior Tories expect Badenoch, the Conservative leader, to use her conference speech to announce her support for withdrawal as part of a broader package of reform. Robert Jenrick, the shadow justice secretary, has long advocated leaving, insisting last year that his party would “die” unless it promised to pull out.

The shadow attorney general David Wolfson, who has been conducting a review of the impact of the ECHR, has produced more than 200 pages of closely argued legal analysis, including around 500 footnotes, which will set out the problems created by the convention and other international treaties. The conclusion is understood to be that leaving the ECHR is “necessary but not sufficient” for the UK to take back control of its borders. “It’s certainly legally possible, and it will make a difference, but it’s not a silver bullet on its own,” one senior Tory says.

The government is close to announcing its own reforms. Shabana Mahmood, the new home secretary, is planning a “twin track” approach and intends to move fast, according to an ally. She will introduce legislation within weeks to clarify the interpretation of the ECHR in British courts, particularly the “right to private and family life” protections covered by article 8 of the convention. Over time, she is determined to work with other countries that also want to see wider changes to the ECHR and the way in which it is applied.

Richard Hermer, the attorney general, has become convinced that the government needs to act to deal with growing public concern over human rights laws. He told the Lords constitution committee last week that “nothing sensible or practical or effective will be off the table” to deal with the small boats crossing the Channel.

“There’s definitely scope for reform,” one source close to the government’s main legal adviser says. “His view would be that a lot of the challenges we are facing are about how our domestic courts apply the law, and clarificatory legislation could help... But there is also a longer-term agenda here, as we know mass migration is going to continue, which we should be open to exploring.”

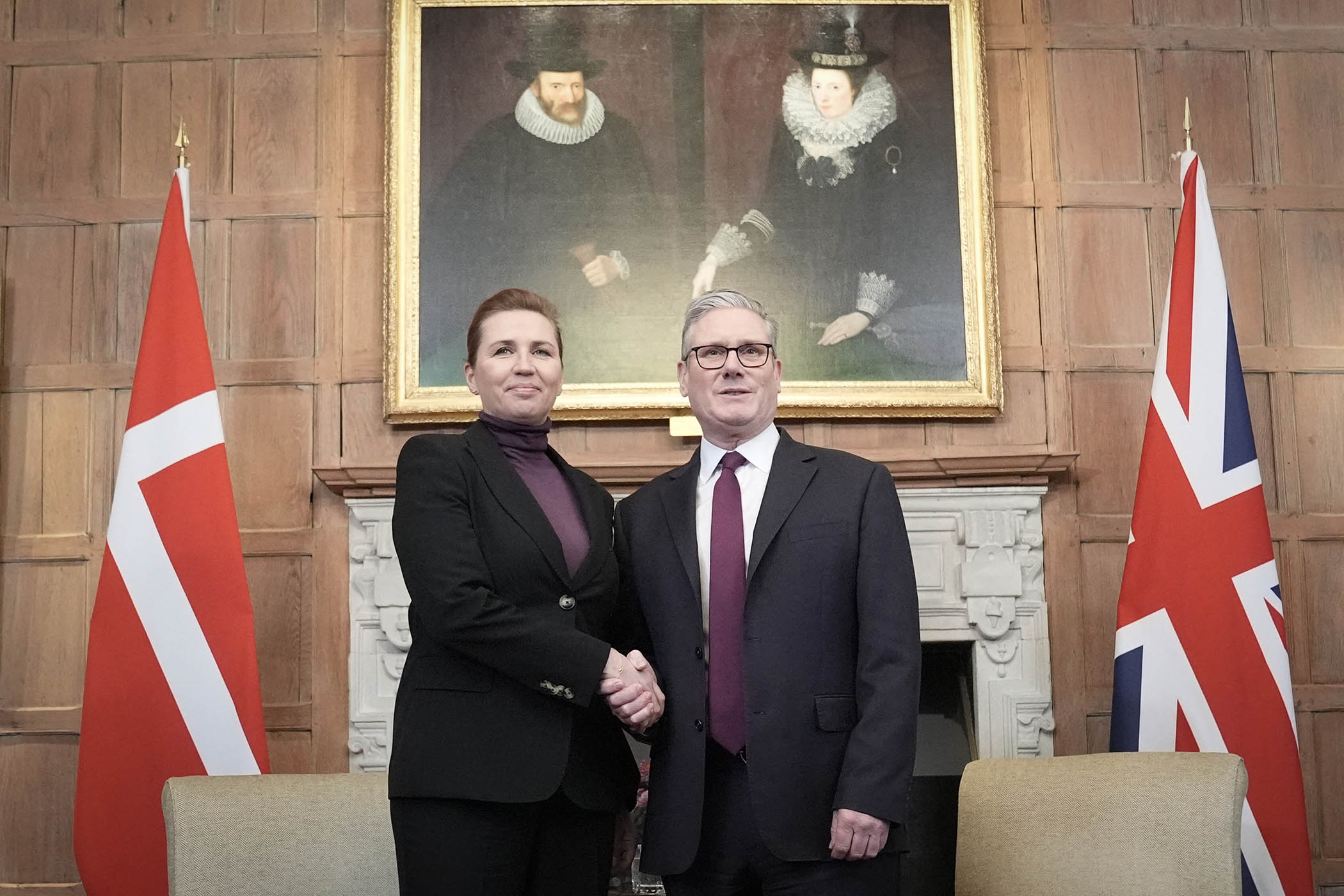

Alex Chalk, the former Conservative lord chancellor, says that when he was in government he detected a “palpable enthusiasm” for change among other countries, including the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. “There’s no reason why the UK can’t be really quite forward leaning on this and say: ‘This is what we think should happen.’ I know from being in Strasbourg that we have enormous influence there.

“The fallacy is to assume that this is all about the ECHR and you don’t need to worry about the broader context. The truth is the refugee convention needs updating, the international covenant on civil and political rights needs updating, and several other pieces of international law besides. Although there is currently a fashionable fixation on one piece of international law, it would be a great mistake to assume that’s where all the problems reside. Urgent and wholesale reform is required – but it’s got to be coherent and wide-ranging.”

Reform UK deputy leader Richard Tice wants to set up an immigration civil servant ‘department of believers’

Professor Francesca Klug, a human rights expert, says: “Withdrawing from the ECHR is like a sacrifice to the gods. It would have little bearing on stopping asylum seekers from coming over on small boats, but it would severely reduce cooperation with other European states.”

There are also practical difficulties. The ECHR is embedded in the Good Friday agreement, which underpins peace in Northern Ireland. Akiko Hart, the director of Liberty, argues that the ECHR has become a “useful political scapegoat”, with rival parties offering “disingenuous solutions”.

David Blunkett, the former Labour home secretary, has called for elements of the convention to be suspended temporarily, while Jack Straw, the former foreign secretary, has suggested that the Human Rights Act could be amended to state that British courts do not have to take account of the ECHR.

But Charlie Falconer, the former Labour lord chancellor, says the idea of suspending or withdrawing from the ECHR is “very dangerous” because it makes human rights conditional rather than fundamental.

“The political pressure now is to abandon rights for immigrants, but if the government feels they can do that for asylum seekers then there is essentially no limitation on what the government may do in other areas where there is political pressure. The ECHR is the guarantor.”

Charles Clarke, the former Labour home secretary, believes it would be “madness” to break with the ECHR. “I think this is an entirely false debate. I don’t believe that if we withdraw from the ECHR it would change a thing in the sense that the rights which the ECHR gives to people are broadly speaking the same rights that existed under British law before the Human Rights Act.”

For prime minister Keir Starmer, a human rights lawyer, this is personal. His biographer Tom Baldwin says he “often described the ECHR and the conception of human dignity defined within it as his ‘lode star’ that had guided him through every major decision in his life”.

The PM’s maiden speech as an MP was about how the ECHR can help people with issues such as housing, and he used his first foreign summit at Blenheim – the birthplace of Winston Churchill, who had been instrumental in drawing up the document – to reaffirm his own and the UK’s commitment to the ECHR.

“Both in public and in private since, Starmer has said he has no intention of joining Russia and Belarus as the only countries on the European continent who are not signatories to it,” Baldwin says.

“Those in the Labour party now suggesting that the prime minister should leave the ECHR either have no knowledge of who their prime minister is or perhaps just don’t care.”

Photographs by Christopher Furlong/Getty Images, ITV, Rasid Necati Aslim/Anadolu via Getty Images