When a neurologist told John Todd in 2023 that he didn’t have Parkinson’s, he was relieved. “Whatever it is, it can’t be worse than Parkinson’s,” he thought. But the doctor told him it was worse.

Todd, who is 67 and from Surrey, had corticobasal degeneration, or CBD, a rare neurological condition. It is in the same family as Parkinson’s, but more acute and rapid in its progress. The trajectory is steep and brutal. Life expectancy is tragically short – about six to eight years from the onset of symptoms – and patients eventually lose the ability to control their body and often suffer cognitive decline as well.

Raynor Winn’s bestselling memoir, The Salt Path, recounts how she and her husband, Moth, walked the 630-mile South West Coast Path soon after he was diagnosed with corticobasal degeneration. The couple say that walking helped reverse Moth’s symptoms and kept him alive for an astonishing 18 years.

It was Todd’s wife, Bridget, who first came across The Salt Path. Todd says he began reading it and was immediately absorbed, believing Moth’s diagnosis to be similar to his own. “I had sort of got used to the fact that the condition couldn’t be reversed, and for a moment, reading the book, it was great thinking maybe it could,” he recalls. “I wanted to believe it.”

Todd says that when he was first given his diagnosis his doctor was blunt with him, describing how the condition would spread across his limbs, that he would be likely to suffer from dementia and either die from choking or pneumonia. There was no treatment, he said, and he told Todd that he probably had only four or five years left.

Related articles:

“He said that this happened in every single case he has observed, so that’s what will happen with me,” Todd recalls. The doctor also said something Todd found harsh at the time. “He said: ‘I don't want you to even attempt to fight this,’” Todd says.

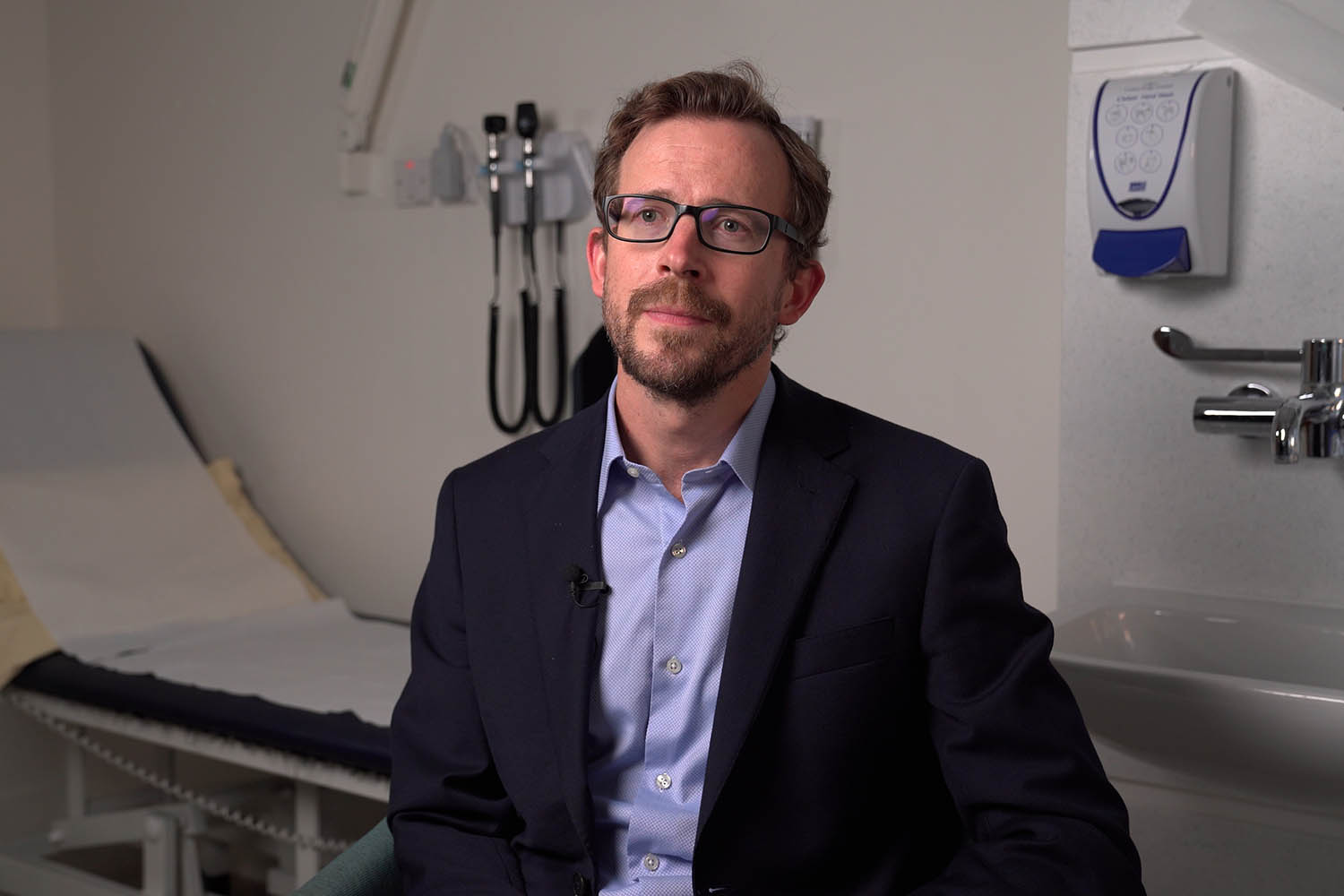

That doctor was consultant neurologist James Gratwicke. He doesn’t remember if he put it quite like that, but he does say: “It’s not a good diagnosis to have to give people. But equally, they need to know what's in front of them.”

He says that knowing what’s ahead is important because then people can use the time they have left to do what really matters while they still have the capacity – whether that’s ticking off bucket-list items or making a will.

‘I haven’t met anybody who has managed to slow their disease down, let alone reverse it’

James Gratwicke, consultant neurologist

Gratwicke has more than a dozen publications under his belt yet isn’t able to offer much to those he diagnoses. “ There’s no treatment or lifestyle factor which has ever been shown to affect the progression of the disease in any way, shape or form.”

Over the past two decades he has treated around 30 patients with this rare condition – the longest any of them survived after diagnosis was eight years, although he has read about people who have survived up to 12 since the onset of symptoms. “But I haven’t met anybody who’s managed to slow their disease down, let alone reverse it,” he says.

Exercise is always a good thing, he agrees. The healthier and stronger you become, the better you will manage the illness. But when asked if clinical trials would be possible to test whether strenuous exercise has a beneficial effect on the condition, Gratwicke says it would be extremely difficult to do because it might be considered cruel.

“To run that kind of clinical trial in people with a condition which affects their physical abilities so much would be somewhat immoral. You would be subjecting them to trying to do physical feats that they could not manage. It would be ethically inappropriate.”

If Gratwicke came across a patient with corticobasal degeneration who claimed to have significantly slowed the progress of their illness, he says he would initially assume they had been misdiagnosed. “I would be struggling to believe it, but if I was convinced that it was corticobasal syndrome [CBS, the symptoms of the condition] and that something had really improved the situation, then I would be jumping to publish that in a medical journal,” he says.

When Bridget read the book, she was confused by Moth’s ability to reverse his symptoms. She knew that when Todd walked to the shop about a mile and a half away, he would come back exhausted, with stiff, painful legs, and then need to lie down.

“But I said to John: ‘Maybe you should walk more,’” she recalls. “I walked as much as I could, and sometimes I overdid it and I felt really lousy,” Todd says.

When he read The Observer investigation, he said that the hope he had was extinguished. “When you are really desperate to believe something, then you will,” he says. “I find it insulting that someone is trying to tell me that this irreversible disease I’ve got – that has no cure – it’s my own fault because I haven't walked enough.”

In response to questions raised by The Observer, Winn published three letters to Moth from his doctors. The first, in 2015, stated that “his condition most closely resembles the corticobasal syndrome... but it is clear that he is affected very mildly”. The doctor referred him to a charity which helps people with CBS for advice. Winn has stated that she never sought to offer medical advice in her books, or to suggest that walking might be some sort of miracle cure. “I am simply charting Moth’s own personal journey and battle with his illness, and what has helped him,” she said.

Sitting in his house in the Surrey village of Badshot Lea, surrounded by photographs of his grandchildren, Todd reads me poems he has written about his condition. It’s difficult to believe he will deteriorate as quickly as his doctor has predicted.

But Todd isn’t afraid of death. “In many ways, I’ve had more trouble with living than I ever will with dying,” he says. “Now that I know what’s going to happen, I can start trying to put a few things in order – and I have a lot of stuff to do.”