Over recent months, during Rachel Cooke’s absence, our ideas meetings at The Observer have been punctuated by a repeated refrain: “Rachel would have been so great at that”; “That would have been a perfect Rachel Cooke piece”; “When Rachel is back, she’ll have so much fun interviewing him/her/going there/investigating that…”

The truth is, that refrain applied equally to just about any idea you could come up with. Because Rachel could not only do everything as a journalist – fearless and funny commentary, ego-piercing interviews, campaigning social reporting, erudite and blistering book reviews, taste-making food writing, courageous foreign reportage – she could invariably do it all better, and quicker, than anybody else.

In the past few weeks, as grim updates on the last stages of Rachel’s brutal cancer ordeal have arrived from her beloved husband, the writer Anthony Quinn, I’ve been in the habit of dipping into her back catalogue, partly to marvel again at the sheer range of her curiosity, partly to remind myself exactly what we have been missing.

You can take any month in the past quarter-century of The Observer and find more than a dozen memorable pieces with her byline. These, for example, are all from a short year ago, November 2024: a withering evisceration of Nadine Dorries’s memoirs; an affectionate account of refusing to be intimidated by John Prescott; a moving interview with the crossbench peer Lola Young about her childhood in care; a behind-the-scenes look at 30 years of Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake; a column on the sad decline of regional difference in food (“You say bap, I say bread cake”); effortlessly brilliant essays on Joan Didion and Wallis Simpson; a celebration of the winner of that year’s graphic short story competition (a genre that she championed and a prize she helped to create); and a thoughtful, nuanced diary about spending Donald Trump’s re-election night listening to Brahms at the Royal Festival Hall…

As those stories indicate, Rachel had that priceless ability to switch tone and register from brimming excitement about simple pleasures to clear-eyed no-nonsense about the often depressing ways of the world. She had – in her writing and in her conversation and in her life – both winning warmth and righteous outrage, often side by side. As one former editor, Nicola Jeal, now of the Times, recalls: “Everything, every single subject she would approach with absolute rigour and curiosity. Whether you asked her to do something silly as I often did – I got her to try Botox once – or to interview somebody incredibly powerful, she would always, always find the story.”

Rachel got the bug for journalism early. Katharine Whitehorn, the pioneer of exuberantly stylish feminism on this paper, was her role model. “For a long time,” Rachel once wrote, “I kept a note hidden inside my diary: a piece of paper that, in extremis, [when writing] I’d take out and prop against the lamp on my desk. The note read: "HAVE GOT JOB ON PICTURE POST WHICH I WANTED MORE THAN HEAVEN…” The words came from a telegram Whitehorn had sent to her parents in 1956, when she landed her first longed-for reporter’s job. Rachel herself never lost that same pinch-me feeling. “Katharine was the reason why, even as a little girl, I never wanted to be anything other than a journalist,” she wrote, “and she was also one of the presiding spirits of a book I would write much later [Her Brilliant Career] about some career women of the 1950s.”

Like all writers of note, Rachel was an acute observer from childhood; she would bow to no one in her memory for the precise tragicomic detail of schooldays in the 1980s – the lip gloss, the Phil Oakey hair, the romantic betrayals. She grew up mostly in Sheffield, where her father was an academic, a lecturer in botany, at the university. There were, though, in the midst of this South Yorkshire childhood, three years in which the family lived in Israel and Rachel, from the age of 10, went to a Church of Scotland school in Jaffa, outside Tel Aviv, one of the few places where Arab and Jewish children were taught together. The dislocation, you suspect, and the excitement, helped develop in her the two key gifts of her writing: the ability to make intimate connections immediately and an outsider’s storytelling eye.

In a piece about returning to that school several decades later as an adult, Rachel recalled how she would barter the KitKats in her lunch box for hot bread with za’atar from the local market that her pal Sammy Waked would run out to get, the taste of his Palestinian home. That sense of food as a connector of people, a builder of community, never left her.

In the introduction to the recent book Kitchen Person, a collection of her food writing, she wrote beautifully of how it was through mealtimes that she came to understand her family history – her mother’s side from the north-east, her father’s from the Black Country – and how it was food that held her idea of family together, even after her parents split up.

She retained that emotional connection to lunch and dinner; she would invariably roll her eyes at any mention of diets or dry Januarys. Her appetites were infectious. As Allan Jenkins, her longtime editor on Observer Food Monthly recalls her saying: “I’m no more a food writer than an opera writer. I’m just playing the role of the enthusiastic amateur, which is what readers are.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The other great sustaining thread through Rachel’s life was books; she was as greedy a bibliophile as a gourmand. In one of her last pieces for the paper in June, she wrote of her nostalgic affection for the Puffin Club, and of waiting with expectation for its magazine – with heady news of favourite authors Rosemary Sutcliff and Alan Garner – to fall through her letterbox.

She was a fierce advocate for public libraries, that great engine of self-education, that helped her get from her comprehensive school to Oxford. In a wonderful long-running column for this paper, Shelf Life, she brought all that vivid sense of value to neglected books that she loved.

She was a great interviewer full stop, but it was perhaps in her profiles of writers – Gore Vidal, Robert Caro, Gloria Steinem, Barbara Kingsolver – where her voice was most alive: precise, conversational, closely attentive to both the sublime and the absurd, and never shy with her opinion. (That quality extended beyond her work: there wasn’t – fabulously – a meeting or a lunch or a party from which you ever came away unsure exactly where Rachel stood on any issue.)

In all of this, of course, she was a newspaper’s dream. She began on the Sunday Times, where, among other things, she edited AA Gill (he would slip filthy obscenities into his copy and laugh uproariously when she called to delete them); she wrote a wonderful television column for the New Statesman, but it was at The Observer where she found her home. In the past days, every editor she worked with has mentioned to me her extraordinary standards and work ethic and sense of fun.

Jane Ferguson, for 20 years her editor on our New Review, thought of Rachel always as “the backbone of the paper. She had intellectual ballast, lightly worn, authority, bite, humour and positively fizzed with ideas. Despite filing over 100,000 words annually over decades, she somehow still had time to read and see everything. She was a star!”

Paul Webster, the paper’s editor for part of that time, recalls her recent piece on the coronation of King Charles as one among many highlights: “Utterly magnificent – beautifully written, wonderfully observed, intelligent, witty, affectionate – the very essence of Observer craft and values.” He thought her “simply unbeatable”.

Some might argue that Rachel’s gifts warranted greater concentration; that there could have been more than three books to her name. I think she would be with me in not subscribing to that perceived writers’ hierarchy. She cared deeply about books and art and music and fashion and politics but, above all, about people, their daftness and their dignity; the newspaper was the perfect vehicle for relaying all the delights and frustrations she found in them week by week for her readers.

At a long lunch in April this year, just before her cancer diagnosis was confirmed, we talked about all the brilliant things she would write for The Observer under its new ownership. Her ideas filled page after page of my notebook. Even in the first month after her alarming test results came in, she insisted on writing 20,000-odd words on every subject under the sun: “Just to show what I could still do.”

She was only 56. There is wonder that so much of her journalism is in the world – and that who she was shines through each sentence of it – but there is also that sharper sadness: she had so much more to write.

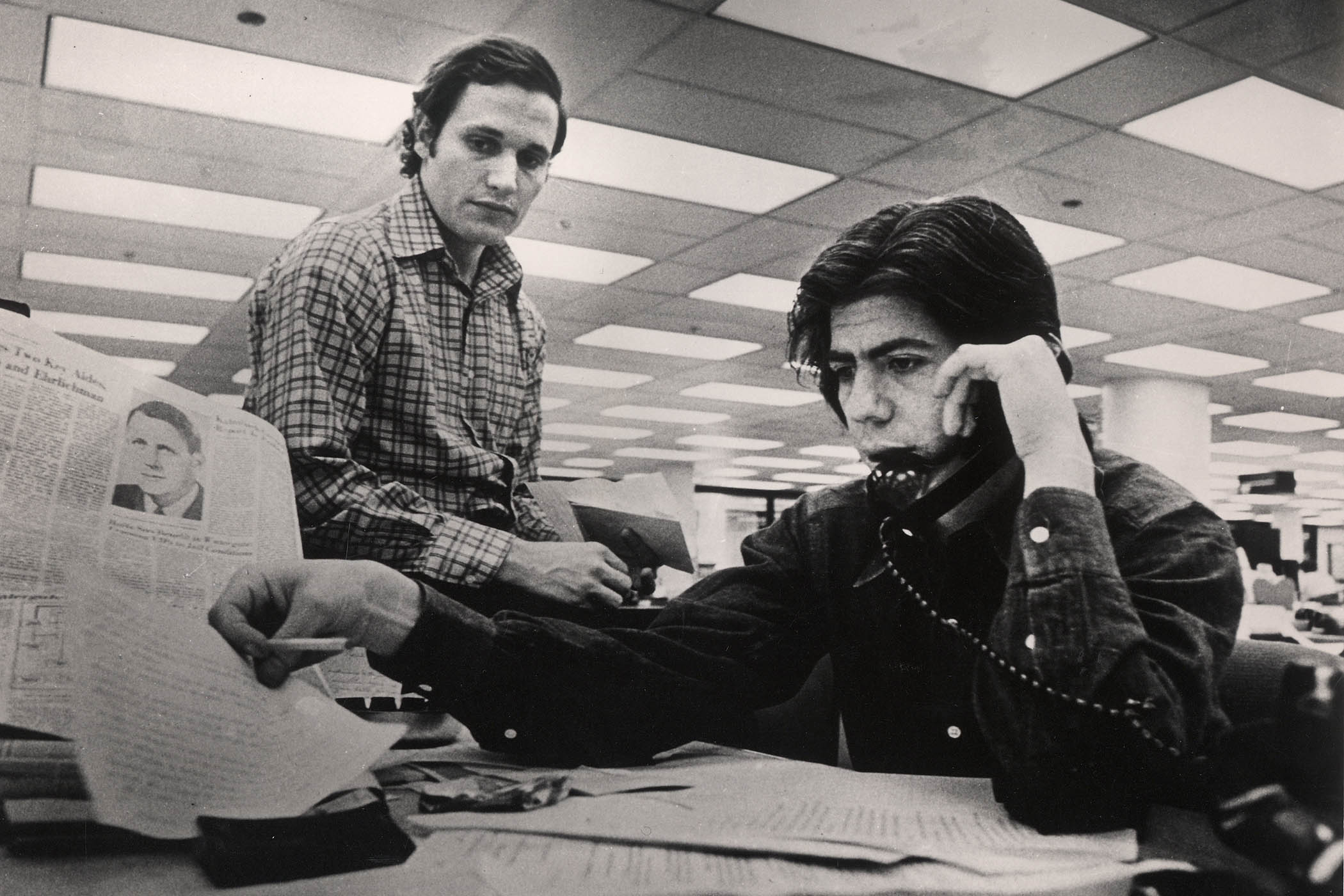

Photograph by Paul Stuart