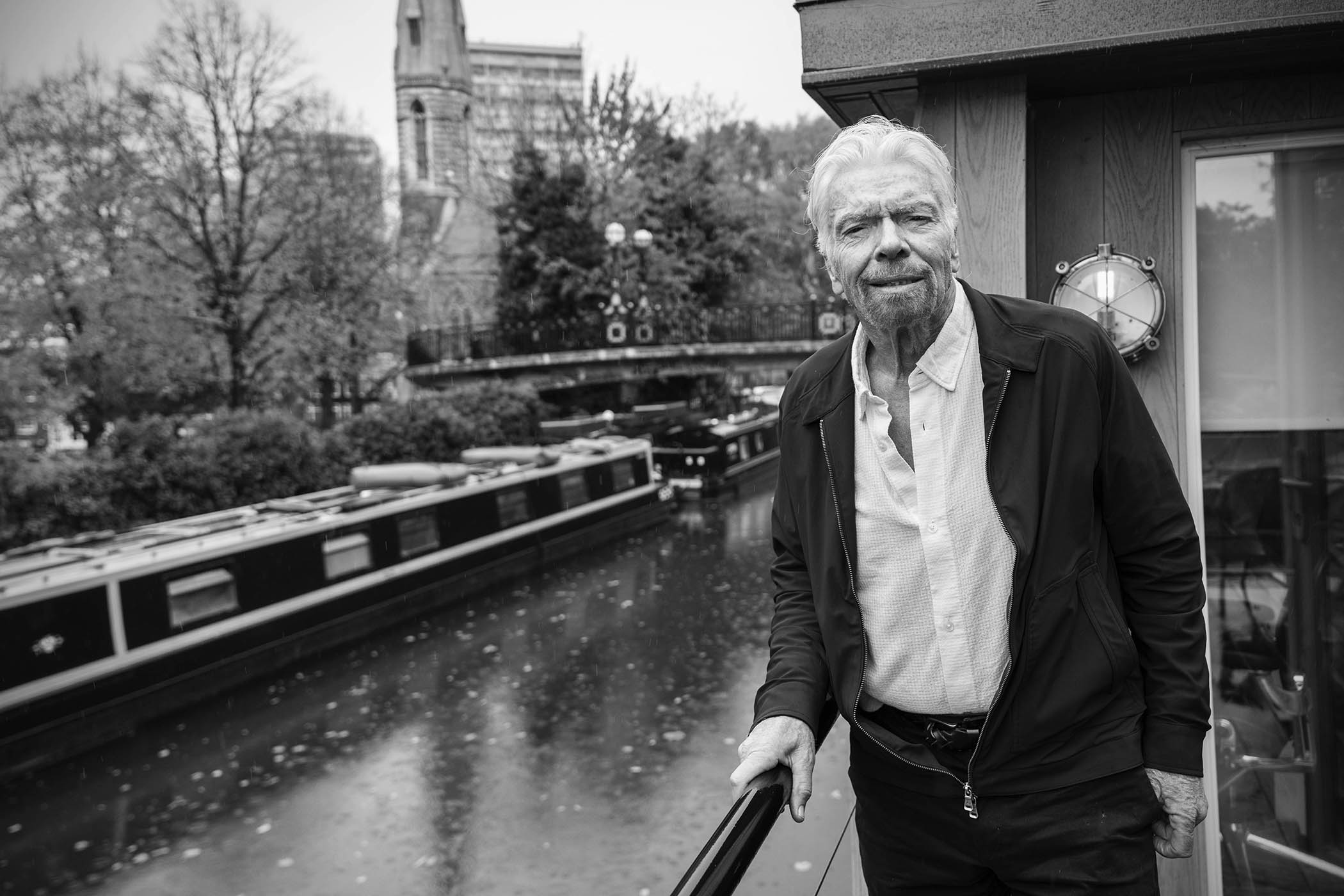

When Richard Branson took me on a walk through Notting Hill, west London, a few weeks ago, he was looking forward to February and celebrating the 50th anniversary of meeting his wife, Joan. “She’s got her plans, I’ve got mine and we’re both supposed to be surprising each other,” he told me. Joan was not ill. There was no reason to worry about her.

Then on Tuesday a heartbroken Branson announced that his beloved lifelong partner had died unexpectedly at the age of 80. Joan had been in hospital in England after sustaining a back injury. Branson was in a room just down the corridor from her, having been transferred there after coming off his bike in India and hurting his shoulder.

“We laughed together about how typical it was of us to end up on the same floor, like love-struck teenagers delighted to find each other again,” he wrote. She was in “positive spirits and getting stronger”, then suddenly “she was gone, quickly and painlessly”. He was by her side when she died. He has not revealed the cause of her death.

‘I didn’t have the money to buy an island but they showed us Necker and we fell in love with it – and I fell in love with her’

‘I didn’t have the money to buy an island but they showed us Necker and we fell in love with it – and I fell in love with her’

Richard Branson

Just weeks before, our route took us from Vernon Yard, the once run-down mews where he had his first office, to the houseboat he lived on with Joan when their children were young because it was the only home they could afford. It was, the 75-year-old entrepreneur said, “where it all began”.

And Joan – his “rock” and “guiding light” as he put it in his statement last week – was woven through the conversation from the start to the finish of our walk.

As we sat down for coffee in the Notting Hill Bakery on Portobello Road before setting off, Branson reminisced fondly about meeting his wife. “I fell in love with a gorgeous girl who worked in a little bric-a-brac shop called Dodo’s just along there,” he said. “It sold things like ‘Dive In Here For Tea’ and Coca Cola signs. The owner said I was only allowed to go in and see Joan if I bought something.” He filled the houseboat with vintage signs, and when he ran out of space he gave them to people as presents. One that read “Now That’s What I Call Music” went to his friend who ran Virgin Records. “He put it above his desk and when we were trying to think of a name for a compilation series of all the greatest hits, we looked at it. It turned out to be the biggest hit series in history, all because I was trying to woo a girl.”

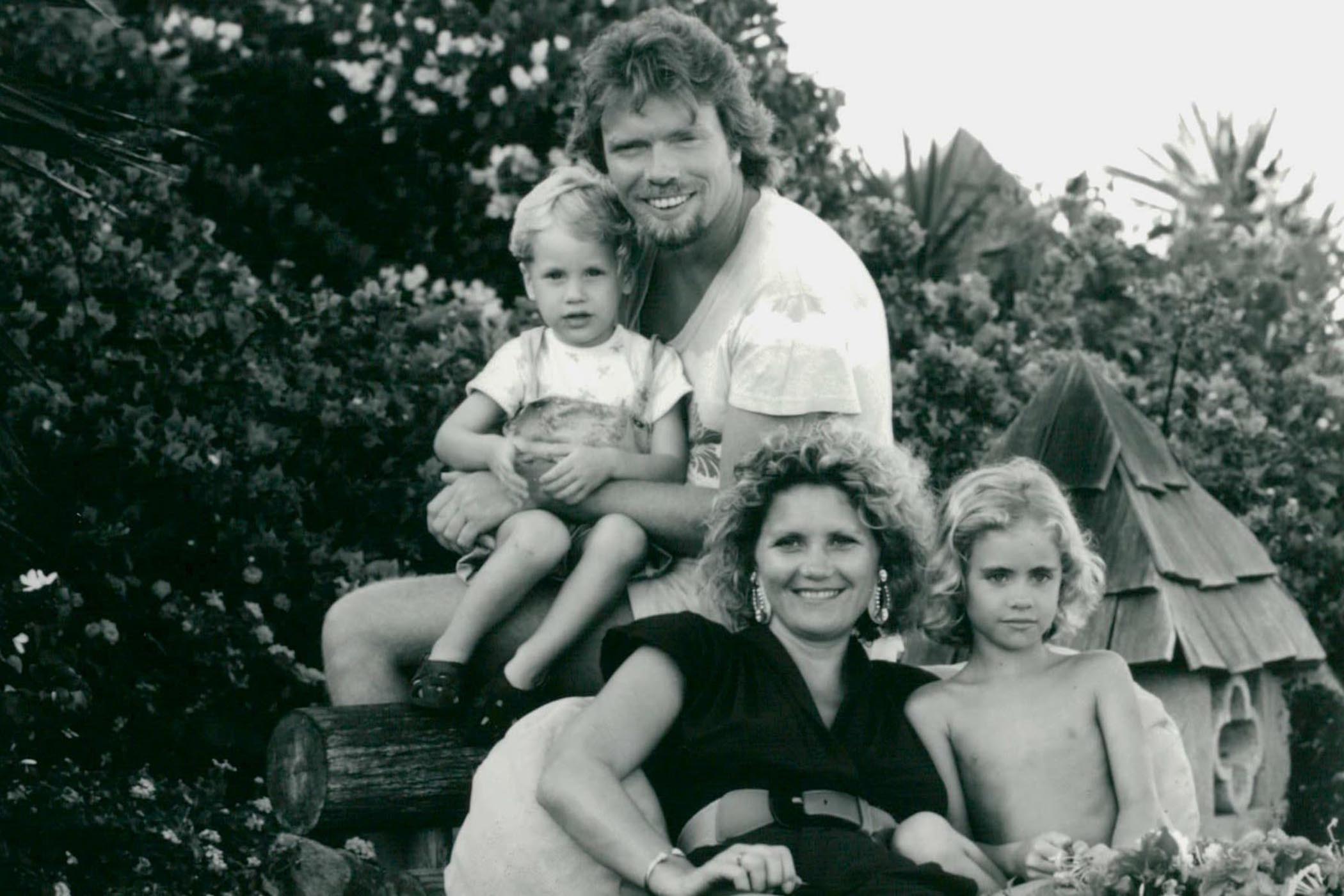

Branson had to try a bit harder to win over Joan. “I rang up an estate agent and pretended I wanted to buy an island,” he said. “They did exactly what I hoped. I was only 28 at the time but they sent me two plane tickets. I sent her one and said, ‘I’ll be at terminal such-and-such if you’d like to come for the weekend.’”

Branson on the deck of the houseboat Duende, where he and Joan lived with their young family

He had no idea whether she would turn up, but the grand romantic gesture paid off and they went to the British Virgin Islands together. “I didn’t actually have the money to buy an island but they showed us Necker from above and we absolutely fell in love with it – and I fell in love with her.” The asking price was $6m. Branson offered $80,000. “We had to hitch hike back to the airport.”

A year later the agent rang and said the seller would accept $120,000, so he “scrambled together the money” and bought it. He eventually married Joan on Necker Island in 1989 – their two children, Holly and Sam, then eight and four, were at the wedding. “Luck plays a big part in life,” he said.

Like Branson, Notting Hill is a lot wealthier now than it was in the 1970s. There are more hedge fund managers than hippies these days, but the businessman thinks the area retains elements of its old character – a creativity and independence of spirit. “It was definitely cheaper in those days but I wonder whether it was so different.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

As we strolled down Portobello Road, Branson pointed to the small house that was once Virgin’s headquarters. “We were teenagers. We dressed as we felt comfortable. You would never see a tie anywhere near a Virgin company. We were just doing what we liked and what we enjoyed.” Before long he had taken over most of the mews.

Around the corner in Notting Hill Gate was the first Virgin record store. “We threw cushions on the floor and put up a counter. There would be queues of kids around the block. A lot of them never bought anything. They would just come in to hang out and listen to music.” The recording studio was down the road. “That’s where I remember sitting when Phil Collins did In The Air Tonight. We had a stone drum room where he recorded that wonderful haunting solo.”

He remembers the thrill of signing the Sex Pistols in 1977. It was the year of the Queen’s silver jubilee and the punk rockers provoked outrage by sailing down the Thames performing God Save the Queen, denouncing the monarchy as a “fascist regime”. The song was promptly banned by the BBC and Branson soon realised that there was no such thing as bad publicity.

When Virgin was prosecuted for displaying the word “Bollocks” in a record store window he mounted an ingenious defence. “I rang up a linguistics expert. He said ‘bollocks’ was a name given to priests in the 18th century, so the literal meaning of the album was ‘never mind the priests, here’s the Sex Pistols’. Then he paused and said, ‘I happen to be a priest myself. Would you like me to wear my dog collar in court?’” The judge found Branson not guilty.

“I always make myself promise never to look back and say ‘that was a great decade’,” he said. “My life has been extraordinary and fascinating every year but that was an incredibly exciting time. We were discovering so many talented bands. The Sex Pistols got us the Human League, Boy George, Simple Minds, Janet Jackson, then the Rolling Stones.”

Branson now has a knighthood and a fortune but he still likes to think of himself as a maverick. He hates the word “billionaire”, describing himself instead as an “entrepreneur” and “adventurer”. His grandchildren think he is a “good pirate who was dumped on Necker Island by the bad pirates” and there has always been something of the buccaneer about him. “I went to the House of Lords for the first time ever last night and I definitely didn’t think I was part of the establishment,” he said. “I’d be happy to be a rebel with a cause.”

He has always been a brand as much as a businessman, a disrupter who loves to “tilt at big companies” as he puts it. Having taken on the airline industry and the cruise giants, he is now challenging Eurostar’s monopoly to run trains through the Channel tunnel. He prefers “the David mindset” to the strength of Goliath. “If you’re smaller you can be more nimble. It’s exciting.”

The Branson family

As we walked, he explained that innovating is the secret of his success. “When we started, I don’t know whether the word ‘entrepreneur’ even existed. Everything was run by the government – British Airways, British Gas, British Steel, British Coal, British Telecom. These were big, badly run companies and I was having fun creating things. I didn’t really think of myself as a businessman. I never got accountants to work out whether it made sense. I just got on and did it.”

He thinks Britain needs to do more to encourage that can-do risk-taking attitude now. “Entrepreneurs should be able to help pull it back to being a great thriving prosperous country again,” Branson said. “Why do British people go to San Francisco to build their AI companies? Britain needs to work out ways of making sure we are ahead of the curve.”

We turned on to Westbourne Grove past the boutiques and florists that have moved in since he moved out. It started to drizzle, so we sheltered under umbrellas but kept marching on. From the age of five, his mother would “shove him out of the car” and tell him to make his way to his grandmother’s house several miles away. “I’ve never stopped walking since then,” he said. “My mum wanted us to stand on our own two feet and I’m grateful for that. She was adventurous and encouraged us to be adventurous. It’s got me into many close shaves but life’s been far more interesting and rewarding because of that approach.”

He has almost died multiple times as a result of his daredevil escapades and flirted with financial ruin on more than one occasion, but he remains a determined optimist. On the back of the magazine he published as a teenager, he printed “the brave may not live forever but the cautious do not live at all” and says it has been his mantra since.

Things could have turned out very differently . When Branson dropped out of school at 15, his headteacher told him he would either end up a millionaire or in prison. He is severely dyslexic and his earliest memories of education are looking at “mumbo jumbo” on the blackboard and relegating himself to the back of the class. “Conventional schooling passed me by,” he said. “I just wasn’t interested in it – all that geometry and algebra. I could just about add up, subtract and multiply and that’s all you need. A business is about creativity and people.”

He was not diagnosed until his 20s and for years thought his inability to spell was a disadvantage. Now he says: “Dyslexia is a superpower. My brain is wired slightly differently from others. I think, because I’m dyslexic, I’m a better delegator and a better listener. That is the main attribute of a good leader. You need to learn from others.”

We turned towards the Westway. Over the decades, Branson has had dinner with eight prime ministers. He was Margaret Thatcher’s “litter tsar” in the 1980s and was put forward for his knighthood by Tony Blair in 2000 for “services to entrepreneurship”. What does he think of Keir Starmer?

“I don’t think we’ve ever met,” he replied. He has always avoided being tied to a political party but clearly finds the lack of long-term thinking in Westminster frustrating. “I’ve spent 55 years learning about building businesses in lots of different sectors. Politicians may be in their job for a couple of years and if they’re good they’re moved to another department. I don’t envy them.”

He now spends most of his time thinking about social issues and global causes. He insists education reform is crucial to end the “one-size-fits-all” system that makes dyslexics feel like failures – and he is convinced it is time to end the “war on drugs”. “Drugs should be treated as a health problem not a criminal problem. If you ask the average person who has a child with a drug problem, ‘Do you want them to go to prison or do you want them to be helped?’, they will respond ‘we want them to be helped’.”

Possession should, he argues, be decriminalised and addicts treated rather than punished. “The negative effects of drugs being illegal has meant thousands of people in prison, thousands of people getting killed. There’s no control,” Branson said. “It’s easy to be ‘tough on crime’, but it hasn’t worked. If you’re a drug addict the only way you’re going to get your drugs at the moment is by breaking and entering somebody’s house or selling drugs, so it’s a self-perpetuating problem.”

The rain was pounding down when we arrived at the houseboat. It is called Duende, which means “the power to attract through personal magnetism or charm”. We knocked on the door and the man who lives there now invited us in. Branson was clearly moved. “I haven’t been here for very, very many years,” he said. The interior has changed completely since he lived here with his young family. “We had our two children crawling around downstairs. It was much more like a family home, a big open space with a lovely log fire and a stove. Poor Joan would have to retreat every time I had a meeting.” They hung a sign on the side which said “please do not feed the baby”.

I asked whether he misses the simplicity of the life he had on the boat and he insisted he is not one for nostalgia. “I don’t generally look back because I love the present, I’m looking forward to the future.”

After our walk, Branson was flying to Miami to meet Joan and finalise plans for their anniversary celebrations. “Life will never be the same without her,” he wrote last week. “But we have 50 incredible years of memories – years filled with tears and laughter, kindness and a love that shaped our family more than words could ever capture.”

Even for this unrelenting optimist, life will be sadder, duller and more lonely without his “shining star”, the woman who was by his side through the highs and lows of an extraordinary life from Notting Hill to Necker.

Photograph by Antonio Olmos/The Observer