‘East of Aldgate one walks into a foreign town”, foreigners “swamping whole areas once populated by English people”. The “substitution of a foreign for an English population” has created “increasing bitterness of feeling”.

No, not Robert Jenrick or Nigel Farage, but William Evans-Gordon, the Tory MP for Stepney, fulminating in 1903 against the arrival of Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in eastern Europe. “Not a day passes but English families are ruthlessly turned out to make room for the foreign invaders,” he told parliament.

Evans-Gordon was a founder of the British Brothers’ League (BBL), a powerful anti-immigration movement with the slogan “England for the English”, and the driving force behind the 1905 Aliens Act, designed to keep out Jewish refugees.

Where previous arrivals had “merged in the population”, Evans-Gordon wrote in The Alien Immigrant, “the Hebrew colony” formed a “permanently distinct block – a race apart”, refusing to “assimilate” but coming “like an army of locusts, eating up the English inhabitants or driving them out”.

They brought with them “colonies of foreign crime". In certain courts in London, “English was hardly heard”. According to Evans-Gordon: “The proportion of aliens who live by vice is inordinately high”. They indulged in “depraved” sexual crimes, “which, but for them, would hardly be known in this country”.

Evans-Gordon’s themes echo across the century. Arguments about populations being replaced, denunciations of asylum seekers as “invaders”, the insistence that migrants are unassimilable, accusations of mass criminality and depravity, are all wearily familiar.

One can even hear in Evans-Gordon the contempt for what many now call the “liberal elite”. The “wholesale displacement of our people,” he wrote, “is regarded with much philosophic calm by their fellow countrymen who live at a distance, whose homes have not been invaded, and who are not subjected to the daily terror of being turned into the streets.” That might have been Matthew Goodwin.

It is not difficult to recognise today how this portrayal of unassimilable Jews draws on deep-rooted antisemitic tropes. It draws also upon ideas of cultural homogeneity and difference still in play today. Across the century, critics have always portrayed immigrants as destructive of local culture.

Cultures, though, are not sealed containers containing a fixed essence that migrants pollute. They are porous vessels, internally conflicted, and changing over time. Nor are individuals fixed by their cultural inheritance, but can also develop and change.

The Taliban has imposed upon Afghanistan deeply reactionary norms, including about the treatment of women, that draw upon one strand of Afghan culture, but which is contested by those for whom Afghan culture means something very different. Half a century ago, Afghanistan was far more liberal than it is today. It is why so many resisted the Taliban and why so many now seek to flee.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

British culture was far more conservative half a century ago than it is today. The social views of conservative Muslims would have, ironically, been closer to that of the British mainstream in the 1970s. Even commentators who now rail against liberalism have absorbed the liberal transformation of the past few decades and, indeed, deploy it as a weapon against migrants from conservative cultures.

Cultures are not sealed containers. They are porous vessels, internally conflicted and changing over time

Cultures are not sealed containers. They are porous vessels, internally conflicted and changing over time

For many critics, African and Asian migrants, and Muslims in particular, cannot be accommodated within the “Judeo-Christian” tradition that defines the west. Yet, as Evans-Gordon’s screed reveals, barely a century ago Jewish beliefs and practices were seen as being as incompatible with British values as many now deem Muslims to be.

The idea of the “Judeo-Christian” tradition is of recent vintage. It became deployed in the 1930s, particularly in America, by those attempting to build public support for the struggle against Nazism, suggesting as it did a common civilisation between Christians and Jews. From the 1950s it was repurposed as a weapon in the cold war, President Eisenhower describing “Judeo-Christian civilisation” as the “fundamental concept” separating America from the atheist Soviet Union. In the 21st century, especially after 9/11, the use of the concept changed again, becoming primarily a means of depicting Islam as standing outside the western tradition and, more recently, of gaining support for Israel in its war in Gaza.

Jewish thought has unquestionably played an important role in the shaping of what we now call the western tradition. That was denied for much of the past 2,000 years. When finally acknowledged, it was in a distorted form, to buttress particular political projects. And both the denial and the acknowledgement became means of defining certain immigrants, previously Jews, now Muslims, as not belonging.

Like many contemporary critics, Evans-Gordon elided his deprecation of immigrant culture with claims that they deprived British workers of basic material needs, from housing to jobs. Again, from today’s vantage point, we can recognise the falsity of such arguments. The material deprivation Evans-Gordon described was real, but its root cause lay not with Jewish refugees but with exploitative bosses, unscrupulous landlords and indifferent politicians.

What transformed working-class lives in the early 20th century was not restrictions on Jewish immigration but the growth of trade unions, an upsurge of collective action and the development of political parties and movements that challenged inequalities. Jewish workers, particularly in east London, were at the heart of these organisations and movements, helping forge solidarity across sectarian divides and in so doing renewing working-class culture. Today, as a new generation of Evans-Gordons try to colonise our attention, that is the most important message to echo across the century.

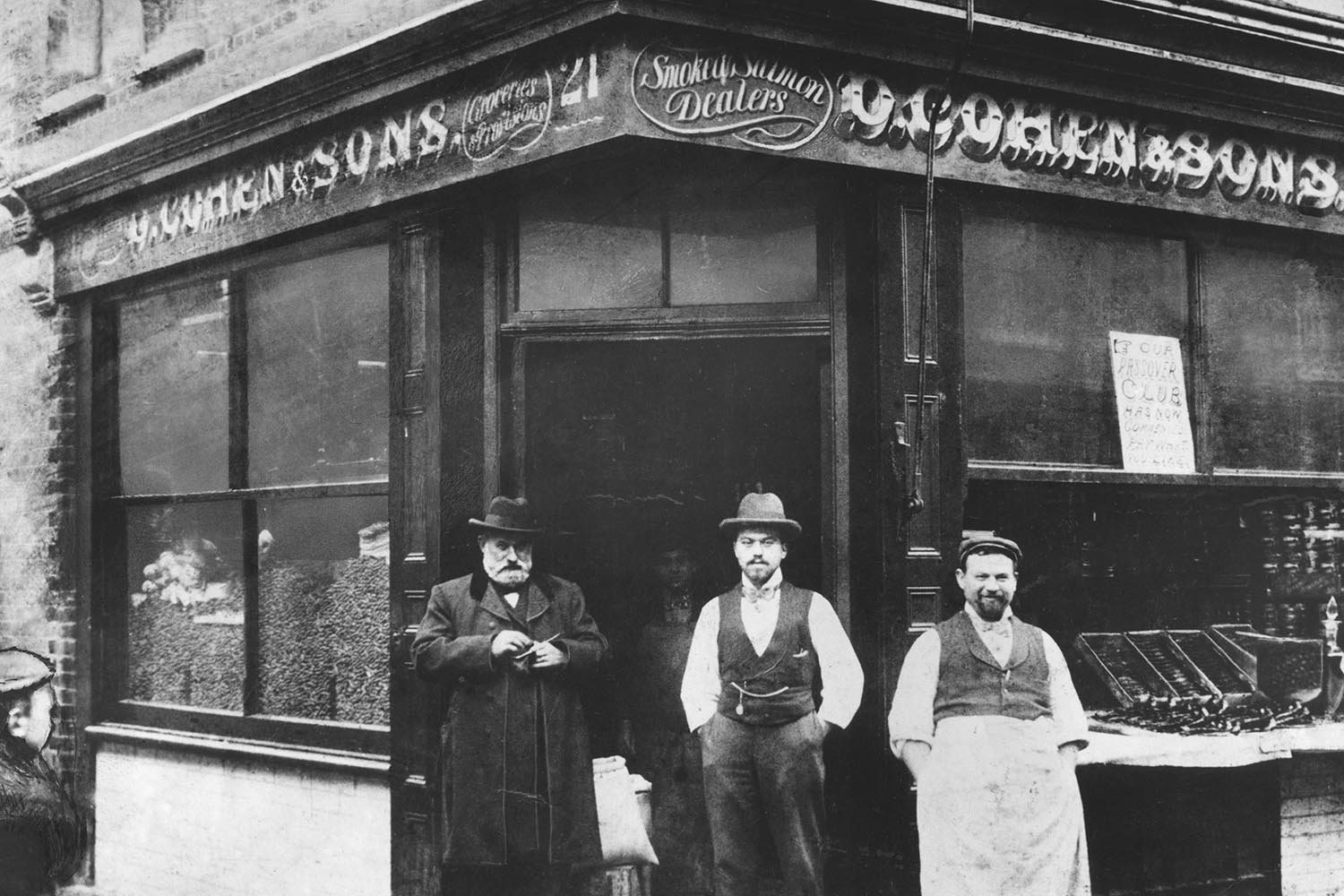

Photograph by Jewish Chronicle/Heritage Images/Getty