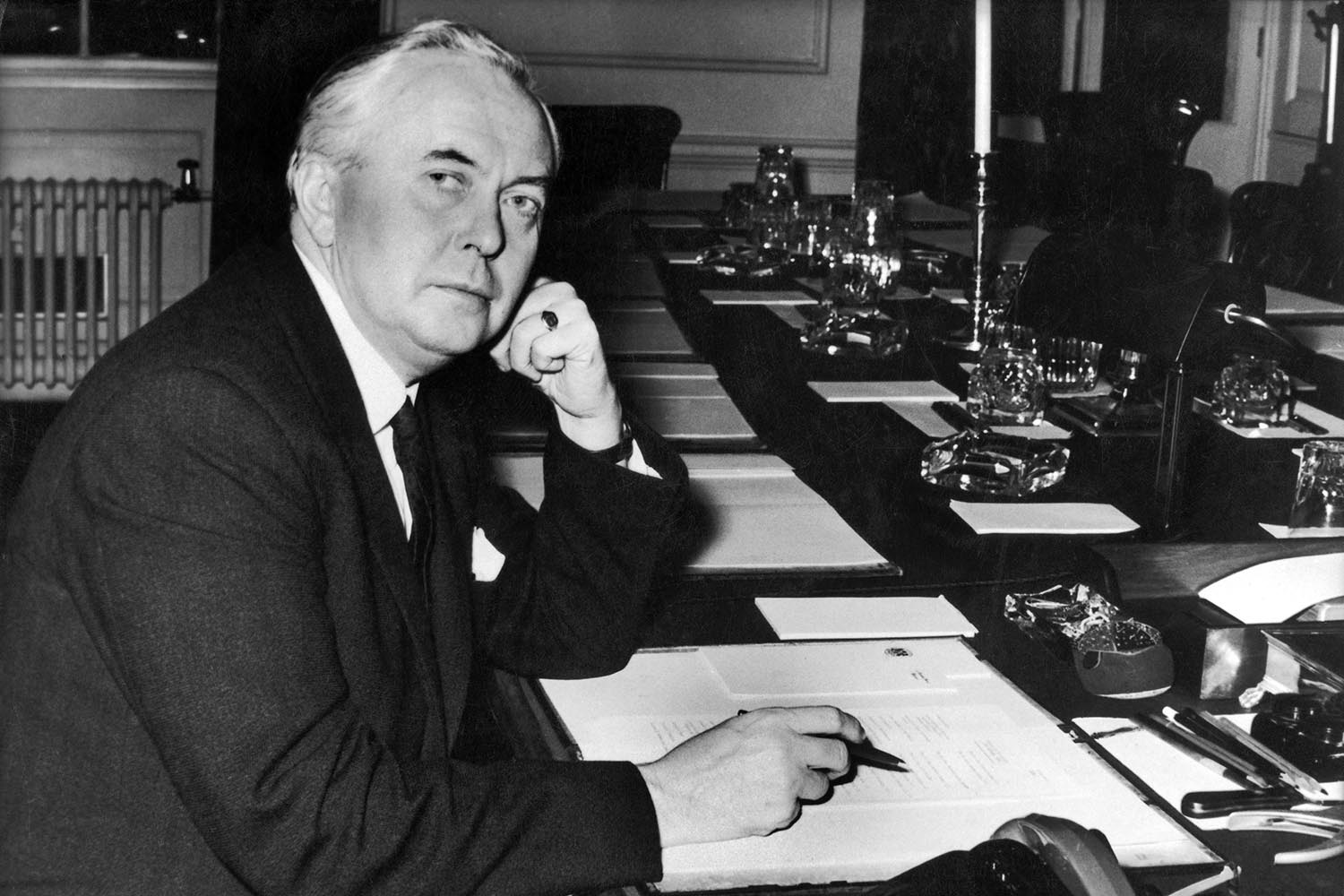

Harold Wilson, the prime minister Keir Starmer most seeks to emulate, once complained that “the only thing we need to nationalise in the country is the Treasury, but no one has ever succeeded”. It might be the only lament Wilson has in common with Liz Truss. The Treasury, so the story goes, has a brain of its own and it is a rigid thinker whose caution holds Britain back. The British economy has grown at less than 1% a year for the last decade and a half so maybe there is a case to answer.

In a report for the Institute of Government, Giles Wilkes, Olly Bartrum and Rhys Clyne give a sober account of the case against His Majesty’s Treasury. Too great a stress on fiscal discipline creates a bias towards the short-term and static institutional thinking. The former chief economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haldane, made the same point in his diagnosis of the two sides of the “Treasury brain”. The “fiscal hemisphere”, he argued, is designed to ensure money is sound. The “growth hemisphere” of the brain is supposed to stimulate growth but, unfortunately, the fiscal hemisphere dominates the growth hemisphere. The Treasury is obsessed with “the saving of candle ends”, to cite an accusation once levelled at Gladstone.

This is a source of great frustration for new chancellors of the exchequer. When he took over the department, Kwasi Kwarteng gave a talk in which he instructed his civil servants to focus “entirely on growth”. In opposition, Rachel Reeves gave a repeated rhetorical commitment that Labour would be all about growth. There would be a savage liberalisation of the planning regime and there would be a potent industrial strategy unleashing the construction of bridges, roads and houses.

Yet Treasury brain and Labour brain have come together. Labour chancellors of recent vintage are anxious to show they command the confidence of markets. If the Treasury sees an economic virtue in spending restraint, Rachel Reeves sees a political virtue. Hence the winter fuel cut. Hence the escalation in defence spending paid out of the aid budget. And hence the absence of a growth plan apart from the ever-ready bits and pieces – a third runway at Heathrow, an Oxford to Cambridge train – that have been gathering dust in the Treasury for years.

If the Treasury sees an economic virtue in spending restraint, Rachel Reeves sees it as a political virtue

If the Treasury sees an economic virtue in spending restraint, Rachel Reeves sees it as a political virtue

The spending review announced today was an attempt to sound like a breaking free from Treasury fiscal discipline. There will be a 3% rise each year for the NHS and £39bn more has been found for housing. However, the 2.3% rise above inflation across all departments includes a one-off boost for the current year. When that is taken into account and the awards to expensive departments of health, housing and defence are subtracted, there is still a beating Treasury brain at work.

We have to be careful not to allow Treasury brain to stand for every critical point. Liz Truss thought the Treasury was full of statist Keynesians; the left alleges that civil servants are all obsessive privatisers. In an elegant lecture given in Edinburgh in November 2022, Nicholas Macpherson, former permanent secretary at HM Treasury, pointed out that, if there is an orthodoxy at all, it’s very volatile. The Treasury had, variously, defended both fixed and floating exchange rates. It had supported public spending restraint in the 1930s, then promoted Keynesian demand management. It was in favour and then against prices and incomes policies.

It is a good defence, but Macpherson does concede that “when the going gets tough, the finance ministry tends to trump its economics ministry function”. That suggests an obvious remedy. Split the growth imperative from the budgetary function that is, indeed, the status quo in all the G7 economies except Britain. Sadly, emulating Harold Wilson here is inauspicious.

Wilson established a Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) in October 1964. The DEA would look after economic planning in the long run while the Treasury would determine revenue raising in the short run. Wilson famously offered the job to his rival, George Brown, during a taxi ride. The DEA published a National Plan in September 1965 but, when Brown moved on, the Treasury clawed back its power. By 1969, the DEA had been wound up.

The failure of the DEA does not mean a revived attempt could not work but time is short. There is a spending review to get through and a tough budget on the horizon. There is precious little time for reforming the machinery of government and there is, in fact, a much quicker fix. The answer to the problem lies with Labour’s most capable Brown. Not George but Gordon.

All observers of the Treasury agree that it will bend to a powerful chancellor, in concert with the prime minister. Nick Macpherson is clear that the Treasury does what it’s told. British membership of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, which ended humiliatingly in 1992, was not a Treasury fix. It was the plan of three chancellors – Geoffrey Howe, Nigel Lawson and John Major – supported by the CBI, the TUC and the Labour party.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The clue to where the power lies is on the famous black door to 10 Downing Street, which bears the legend of the official title of the prime minister – the First Lord of the Treasury. In the end, the politician who knows their own mind is stronger than the Treasury brain.

Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images