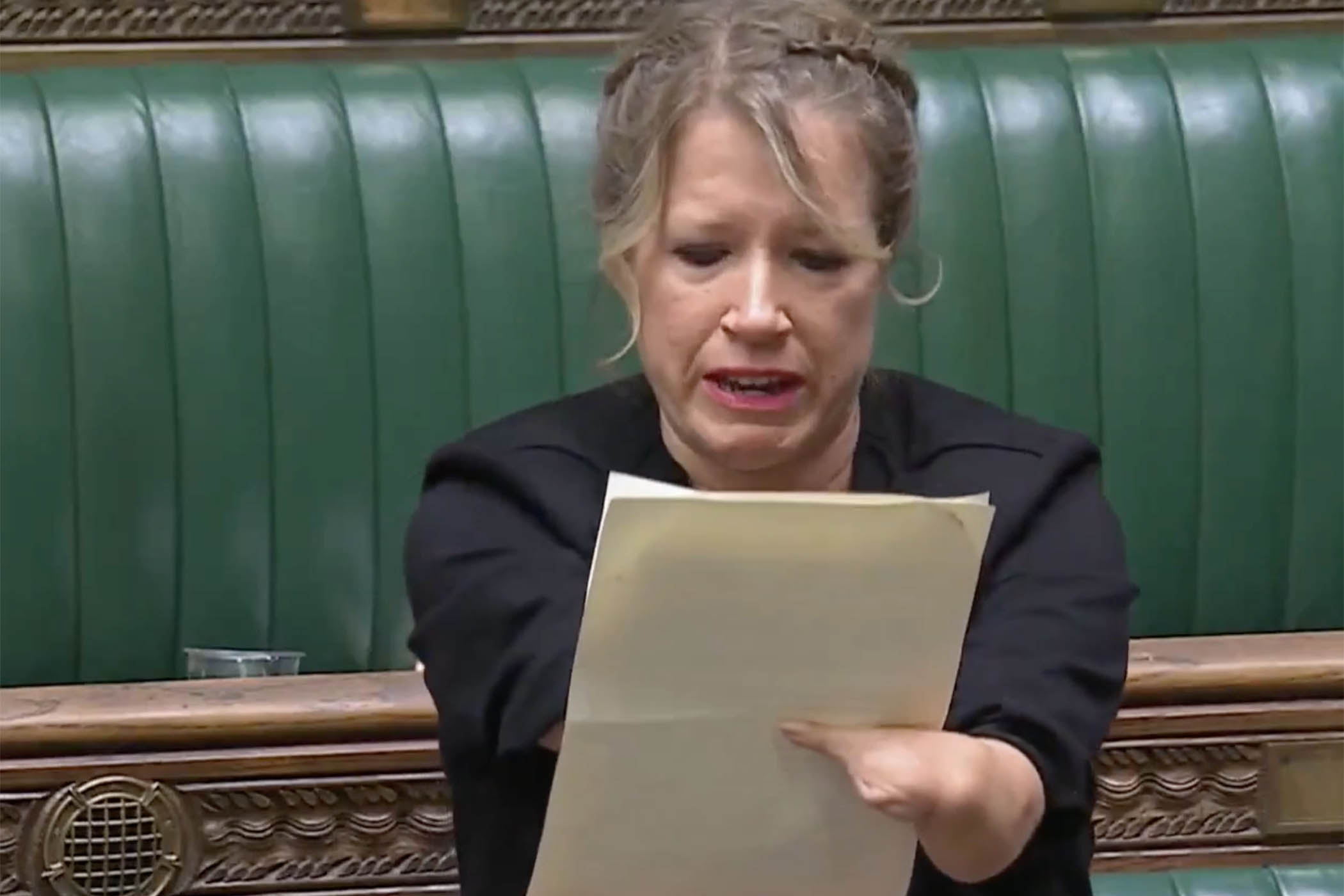

It was “with a heavy, broken heart” that the Labour MP Marie Tidball stood up in the House of Commons on 1 July to say she would be voting against the government’s welfare reforms. Her emotional speech sent a surge of sympathy around the chamber and a frisson of anxiety along the Labour front bench. Tidball, who has a congenital condition that means that all four of her limbs are foreshortened, told her colleagues that “as a matter of conscience” she could not support the proposed changes to disability benefits.

For three months, Tidball had been “engaging relentlessly with the government”, but ministers had failed to take her concerns on board. Her conversation with Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, had reduced her to tears. “Rachel shouted at her and accused her of not understanding the policy,” one Labour MP said. “Marie was very upset through that period and there were lots of colleagues who were really shocked at how they were treated.”

Insiders claim several other backbenchers were made to weep by “bully boy” Downing Street aides. “MPs were being told, ‘Your job isn’t to have opinions – your job is to amplify our messages,’” one Labour source said. In the end, No 10 caved in to the rebels and the plans for deep cuts to personal independence payments (Pips) for the disabled were shelved. A gutted version of the legislation passed, but the welfare revolt was a tipping point for Keir Starmer from which his premiership has not fully recovered.

The tax rises announced in the budget last month were at least in part required to fill the £5.5bn gap left by the climbdown. Labour backbenchers discovered that they could stand up to the government and win, and the bond markets took that as a sign that the leader did not have control of his party. The prime minister’s political authority was shredded – and so was his moral standing with MPs and ministers.

The showdown over welfare also revealed a disastrous disconnect between the parliamentary Labour party (PLP) and No 10, and highlighted a baffling inability to communicate the purpose of a flagship reform.

Around the cabinet table senior figures began for the first time to question the prime minister’s instincts. “It was a watershed,” one minister said. “A lot of people were assuming that because the majority was so big, and Rachel and Keir were so powerful, they would be able to get everything through. But as we got closer and closer to the vote, there was a sense that ‘this is not as ordered as we thought’. It had a psychological effect on the PLP. In government there was a complete reorientation.”

The seeds of the debacle were sown back in March when plans for £6bn of welfare savings were leaked to ITV News. Anushka Asthana, the deputy political editor, reported that the government planned to save more than £5bn by making it harder to qualify for Pips, and cutting the rate of universal credit paid to those judged unfit for work.

The story broke the day after a difficult meeting in No 10 at which Liz Kendall, then the work and pensions secretary, had been resisting Treasury attempts to squeeze the benefits bill before the June spending review. Some senior figures in Whitehall believe the plan was leaked from inside Downing Street to try to “bounce” Kendall into backing the proposals.

Marie Tidball said “as a matter of conscience” she could not support proposed changes to disability benefits

The framing of the policy was a disaster. “The narrative became from that point on that it was all being driven by cuts,” one former cabinet minister said. “It was impossible to pull the argument back to this being about reform.”

MPs immediately “began expressing a lot of concern”, one backbencher recalled. “There was a private letter to the chief whip that had 120 names on it. Everyone signed individually and no one knew who else was on there. It was so secretive that nobody has seen the full list.” Constituency surgeries were filling up with people worried that they were going to lose out but the details were vague. “The figures kept changing,” according to a former minister. “People were waiting to know who would or wouldn’t be affected but no one could answer those questions. They just didn’t know.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Reeves, who had already factored the savings in to her spending plans, was determined to get the reforms through, but other senior ministers were nervous. In cabinet, Ed Miliband, the energy secretary, and Lucy Powell, now Labour’s deputy leader, protested about the scale and pace of the proposed cuts. Angela Rayner, then deputy prime minister, suggested the change should be presented alongside the employment rights bill as a reform designed to help disabled people back into work rather than a money-saving exercise.

‘There was no political management – if the person responsible for it doesn’t agree with it, why would anybody else?’

‘There was no political management – if the person responsible for it doesn’t agree with it, why would anybody else?’

Anonymous backbencher

According to two sources, one rebel and one whip at the time, Kendall herself seemed lukewarm about the package. “Liz was going around telling colleagues she didn’t agree with it,” one backbencher said. “There was no political management – if the person responsible for it doesn’t agree with it, why would anybody else?” The work and pensions secretary was privately pushing for the two-child benefit cap to be scrapped before the welfare vote to help reassure MPs.

The Labour whips, who are responsible for party discipline in the House of Commons, created a colour-coded spreadsheet to identify the rebels – green for those who would back the bill, red for those who would oppose it and amber for undecided. One person who was in the whips’ office at the time said: “For 12 weeks we had been telling [Downing Street] there was a serious issue… And every time someone went into No 10 they were coming out more resolved [to oppose].”

A backbench rebel confirmed: “No 10 were having [MPs] in but they weren’t interested in listening. There were people in tears recounting their own personal stories, those of family or constituents, and being met with complete blank walls. Those meetings were making things worse.”

Claire Reynolds seemed not to understand that only 84 Labour MPs were needed to defeat the government

Claire Reynolds seemed not to understand that only 84 Labour MPs were needed to defeat the government

Starmer’s team seemed completely out of touch. Claire Reynolds, then Downing Street political secretary, told one meeting that “everything was fine” because there would not be more than 100 rebels. Her colleagues were astonished that she seemed not to understand that only 84 Labour MPs were needed to defeat the government.

“No 10 just had their fingers in their ears,” one MP said. “The presumption was that the new intake [MPs elected in 2024] were more compliant than they anticipated and undoubtedly there is a completely out of touch arrogance from the centre that they can dictate to politicians.”

The assisted dying bill, which passed in the Commons on 20 June but had divided Labour MPs, was further evidence that the bond between backbenchers and the leadership had been broken. By the time the welfare vote came along “people had got in the habit of voting in a different lobby to the PM”, one rebel said. Meg Hillier, the chair of the Commons Treasury select committee, Debbie Abrahams, chair of the work and pensions committee, and Helen Hayes, chair of the education committee – three of the most influential welfare rebels – had all voted against assisted dying.

Liz Kendall was “going around telling colleagues she didn’t agree” with the changes, according to one backbencher

In the weeks leading up to the crucial welfare vote, the rebels were focussed, coordinated and highly organised. Each had their own list of MPs to lobby. “There wasn’t a large WhatsApp group – it was much more of a cell structure,” said one of those involved. “We didn’t want the Socialist Campaign Group to take it over. And we didn’t want No 10 getting wind of who the organisers were.”

By 23 June, more than three months after news of the cuts was first leaked, and the week before the crucial Commons vote, more than 100 MPs had given their backing to a “reasoned amendment” attempting to halt the welfare bill. “There were people who had signed it who hadn’t flagged any concerns,” one whip at the time said. “Because it was so intrinsically linked with the spending review, you’re almost entering confidence territory of not being able to pass legislation.”

Cabinet ministers including Rayner and Wes Streeting were sent out to try to persuade the rebels to back down. “Angela was very actively demonstrating to Keir that she is the only person who can be that conduit with the PLP,” one source said. “I don’t know what they would do without her now.”

Rayner helped to set up a meeting between the three select committee chairs and herself, Morgan McSweeney, the prime minister’s chief of staff, and Alan Campbell, then chief whip. “There was no one from [the Department of Work and Pensions] or the Treasury in the room,” according to one insider. “The three of them, none of whom had policy expertise, would go back and say what had been negotiated. Morgan went back to Keir and Keir had to decide whether he was overriding Rachel [Reeves]. I don’t think Rachel knew there were negotiations taking place until they were nearly concluded.”

Eventually a deal was agreed that Hillier and most of the other rebels could live with, although Abrahams was still not happy. Those who had accepted the compromise that would limit the stricter criteria for benefits to new claimants spoke to other MPs to try to persuade them to agree to the concession. “We were feeding names back to the centre and saying ‘someone needs to ring this person’ and no one did,” said one backbencher. “At this point the people who [had been] leading the rebellion were doing more than the government.”

It was chaos. Aware that even the watered-down proposals might not get through, the government was forced to shelve the planned cuts

It was chaos. Aware that even the watered-down proposals might not get through, the government was forced to shelve the planned cuts

It was chaos. Aware that even the watered-down proposals might not get through, the government was forced to shelve the planned cuts in a dramatic last-minute climbdown. Even so, 49 Labour MPs voted against the prime minister.

It was the biggest rebellion in a government’s first year since 47 Labour MPs voted against Tony Blair’s planned cuts to lone-parent benefits in 1997. Harriet Harman, who was then the social security secretary, said the fallout from the revolt is more perilous for Starmer because, unlike Blair, he has an “unvanquished opposition” in the shape of Reform. “He’s the only prime minister who has had no space to make mistakes.”

Looking back, Streeting believes the welfare revolt was “misunderstood” by many. “Everyone pretty much, with a few exceptions, is of the view that we need to reform the welfare system,” he said. “The concern MPs had was about the way it was being done and the timetable upon which it was being done.”

Pat McFadden, now work and pensions secretary, has made clear that he is determined to return to the issue. Lessons have been learned but backbenchers have now got a taste for rebellion. One whip estimates that 80% of Labour MPs who have no government role have either rebelled or threatened to. “We have seen the collective power of the PLP: if they don’t want to do something, they won’t do it.”

Margaret Hodge, the Labour peer and former disabilities minister under Blair, said the government needed to prepare the ground better. She secured changes to disability benefits in the early 2000s with the support of campaigners and Labour MPs after extensive consultation that focussed on carrots rather than sticks. “We set up a disability rights taskforce and by the end everyone had accepted that work was also a right, not just benefits.”

Tom Baldwin, Starmer’s biographer, points out that the prime minister’s mother and brother were both disabled but he refused to draw on this experience because he did not want to “contaminate” his family with “grubby” politics.

“Keir could have explained the government’s plans for welfare reform in a very personal way, saying he wanted to get scarce resources to people like his mum… Instead, he came across like a bean counter who cared only about making big cuts without thinking about their impact,” he said. “The paradox is that this rather unpolitical determination to protect the integrity of his personal story actually makes him look more, not less, like a typical shifty politician.”

Five months on, the prime minister is more unpopular than ever. Some senior Labour figures now believe the revolt was not just the end of the beginning – but the beginning of the end.

Photograph by Justin Tallis/AFP via Getty Images, House of Commons