‘Say something about hope”, I often hear when I address not just Jewish but groups of all faiths, and Hanukah is about hope, courage and inspiration.

The festival marks the rededication of the temple in Jerusalem after the Maccabees recaptured it from the Seleucid Greeks in the second century BCE. The place was in ruins and the war far from over. But what Hanukah recalls is not the battlefield, but the search for a source of light amid the devastation. Finding just one vial of oil, the Maccabees determined to use it, insufficient as it was, to rekindle the lamps of the Menorah. By the laws of physics they should have burned for just one day, but they lasted for eight and their illumination reaches us today.

The mystics understand this as the inexhaustible inner flame of the human spirit which even the deepest darkness cannot extinguish. “It’s the light of compassion,” Bishop Kenneth Nowakowski, spiritual head of the Ukrainian community in the UK, told me. He explained how a man whose wife, daughter and granddaughter had just been killed found comfort among teenagers on a respite visit to the UK after losing a parent in the fighting. “We can say nothing. But the suffering can console each other. Compassion is the light of strength and hope that will never be put out.”

I recalled my meeting with a group of elderly Jews in Kyiv, one year into the war. “My parents were murdered a kilometre away in Babin Yar,” a woman said. “My work was with children with disabilities. When they were evacuated, I needed some other way to care. So now I look after the city’s homeless dogs.” It’s a deep need, this determination to find light amid destruction, this refusal to let the flame of loving kindness be put out.

Fifteen months ago, I received an unexpected gift of honey for the Jewish new year. It was sent from Kherson, from the frontlines of battle, by Leonora, whose granddaughter, Irina, belongs to my community. On the eve of this current new year, Leonora was killed, shot by Russian artillery.

It’s a deep need, this refusal to let the flame of loving kindness be put out

It’s a deep need, this refusal to let the flame of loving kindness be put out

“She refused to move,” Irina told me. “She and her husband built their own home. She lived there for 47 years. For three and a half years of war, she repaired it whenever it was hit. When the Russians bombed the Kakhovka Dam, the waters reached the street below, but she kept on growing her tomatoes in her beloved garden. She had the opportunity to leave, but a house has a soul and she wouldn’t go. And she was determined to send that honey.”

I think of that small jar, perhaps in the way the Maccabees thought of their vial of oil, with its light and faith that transcend whatever destructiveness wreaks. Leonora sent it with the same courage and hope that made the Maccabees kindle the Menorah. Like those flames, what it symbolises reaches far beyond battlefields and borders.

According to Jewish law, the Hanukah candles should be lit in every home as twilight falls and placed outside, or in the window, where the maximum number of people can see them. They are a public declaration of hope.

Related articles:

In my teens, I would often light those candles with my grandmother, a refugee from Nazi Europe. I would watch the reflection of the flames in the window, and the reflection of the reflection, and yet further reflections, in the windows opposite. It seemed to me then as if they were reaching out into the darkness, illuminating a pathway of light across space and time.

Courage and compassion don’t die with those who share them. They communicate their light to countless others and generations yet unborn. A few truly inspired people can change society, said this year’s Reith lecturer, historian Rutger Bregman. But you have to look long term; almost all the key British campaigners who fought against the slave trade died before its abolition. But without them, change would not have been possible.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In these dark days at the close of a dark year, we need to know that the lights of hope and courage reach far beyond where we can imagine and that their flames can never be extinguished.

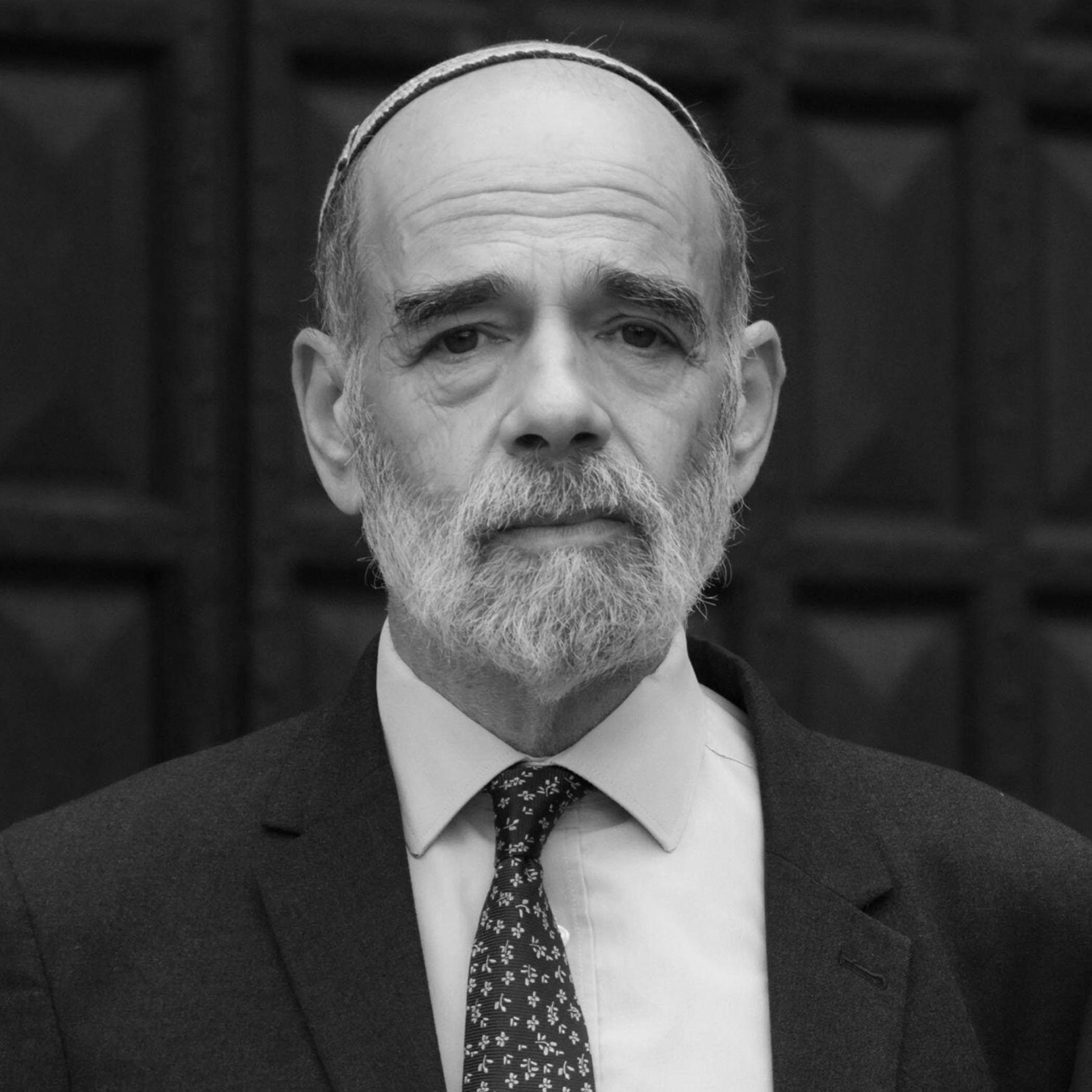

Jonathan Wittenberg is the senior rabbi of Masorti UK

Photograph by Yevhenii Zavhorodnii/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images