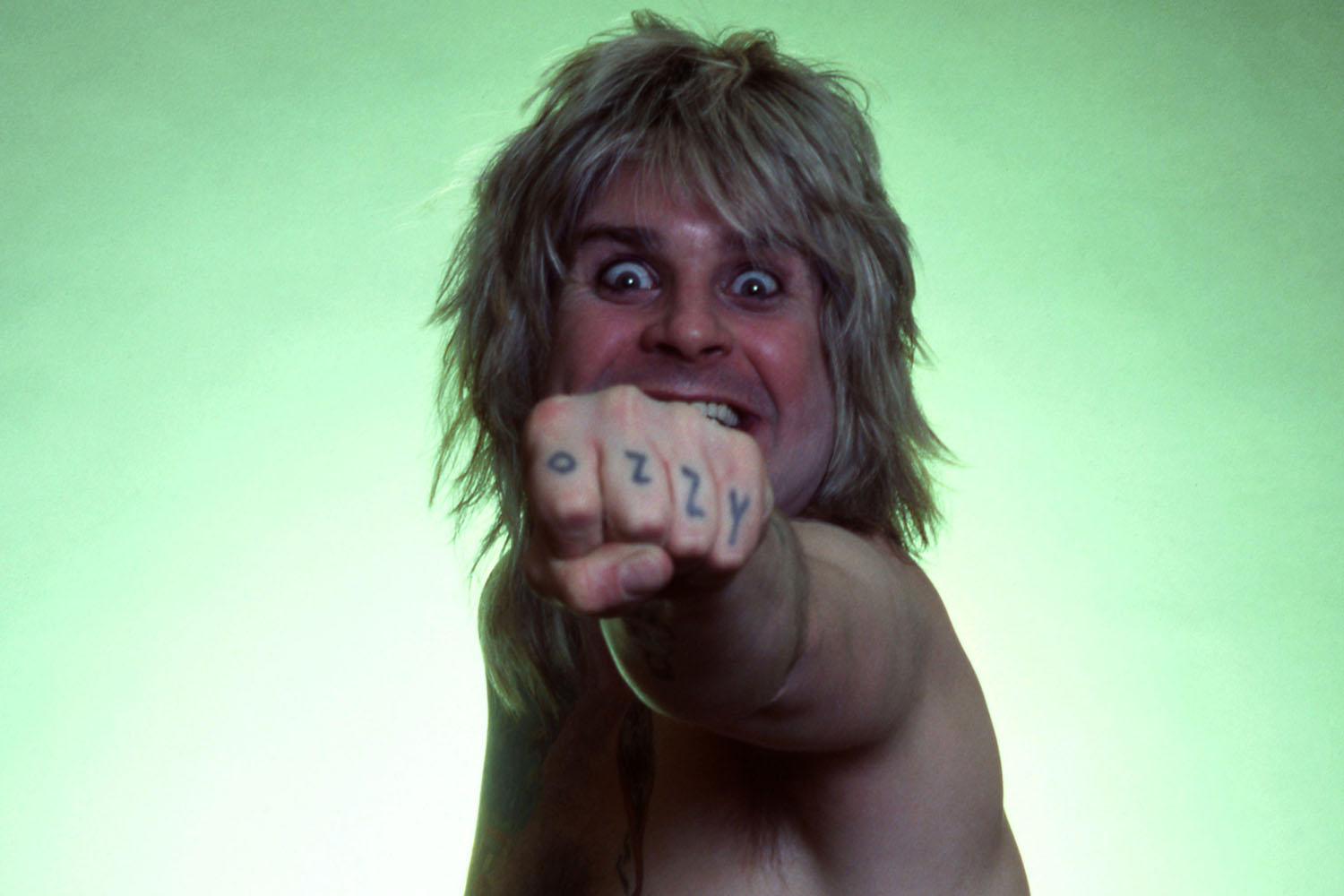

Years after his breakup with Black Sabbath, when asked why he had to leave the legendary group, Ozzy Osbourne said: “I am not in the band any more because of musical differences. They were musical. I was different.”

That difference had not gone unnoticed by a group of young Turkish people in 1990, and I was one of them. It was a time of increasing political instability in Turkey. A military takeover in 1980 had precipitated a climate of human rights violations, systematic torture in prisons and detention centres, and a wholesale crackdown on democratic freedoms. Ankara, at the time, was a city of smog, bureaucracy and repressed dreams. I did not wish to repress mine. I wanted to become a writer. A novelist. I longed to write stories. Even the thought of it was strange, scary, nigh on impossible.

There was a music store that I liked to visit, tucked inside an arcade between a noisy teahouse and a shop that sold crochet dollies and painted wooden spoons. Whenever I went there I would walk through a tunnel of sounds: of dice rolling on backgammon boards, clicking wooden spoons, crying babies … and then I would step into that store teeming with people clad in black, like me. Very often, through the speakers would boom a very distinctive voice: Ozzy Osbourne.

I play some of his songs 90 times on a loop. It helps me to concentrate better

I play some of his songs 90 times on a loop. It helps me to concentrate better

Shortly after that, I moved to Istanbul and in the megapolis I found a lively subculture that appreciated heavy metal. It was not breezy pop songs that we were seeking, or traditional ballads of courage, patriotism and heroism. We longed to listen to something more gruff, raw and perhaps no less chaotic than the Istanbul traffic. The Prince of Darkness Osbourne might have been called, but to us he was someone who clearly struggled with the world he had been placed in – someone who was a bit lost, just like all of us. Many other rock singers carried themselves with the knowledge of having made it, a visible confidence and self-contentment oozing from their demeanour. Ozzy Osbourne wasn’t like that. He looked as if he expected to be kicked off stage anytime. As if he expected to be kicked out of life. The ground beneath his feet seemed to be churning, never settled. That made sense to those of us living in a country where uncertainty was the principle of life. Ours, too, was a liquid world, everything in a state of flux.

The lyrics made sense too. Saddam Hussein in his endless greed had invaded Kuwait, and the Gulf war had shaken the entire Middle East. Everywhere there was volatility, militarism, jingoism. Deep and deepening inequalities.Black Sabbath sang: “Generals gathered in their masses, just like witches at black masses”. They talked about how politicians started wars but never went to fight, leaving the poor to do all the suffering and the dying.

I never forget the first time I listened to Paranoid. True, I was 20 years late, but the magic of heavy metal is its ability to transcend time, trend and geography. A song made in 1970 in England can capture the heart of someone miles and continents away, decades later. This unusual singer from a working-class background in Birmingham felt familiar to us. It was his unpretentiousness that spoke to us. There was such rawness in his voice. Strength but also vulnerability. The contrasts in his music were remarkable. He told us about how “looking back in history’s books, it seems it’s nothing new.” He reminded all that “waste of love” was “waste of life".

For so long, heavy metal has been criticised for being aggressive, negative or simply too dark. But it is life itself that harbours all these qualities, no doubt, alongside harmony, positivity, kindness and light. What heavy metal does is embrace these striking contrasts with unflinching honesty, daring to confront difficult emotions and sentiments. I have written all my novels listening to heavy metal, and quite a number of chapters were composed to the melodies of Black Sabbath or Ozzy Osbourne. I have always found the experience transformative, immersive and profoundly energising. When I like a particular song, I listen to it again and again on a loop – maybe 80 or 90 times. It helps me zoom in and to concentrate better.

One study by the University of Queensland found that regular listeners of the genre are better at managing anger, anxiety or depression. This is no small gift in this Age of Angst. Heavy metal also enhances cognitive function. But the truth is you do not listen to this music because it has a “function” or a purpose. Such things do not even cross your mind — until someone asks you why you are a fan, and then you feel compelled to offer a rational explanation. Yet it is not the rational mind that does the listening. It is something more irrational, visceral, innate, deep down. When you walk into a music shop and stop in your tracks because an astonishingly sensitive, sore voice has caught your attention, there is only one reason why you keep on listening: because it has touched your soul. Because you love it. It is as simple and as as powerful as that.

Related articles:

And that simple power is at the heart of Ozzy Osbourne’s entire musical legacy. Many years and many novels later, I feel like I owe him a debt of gratitude – for all the inspiration, the connection, the company. To the voice that I discovered among the sounds of backgammon and clicking wooden spoons, the voice that accompanied me through the vastness of Storyland, where there are no borders, no hierarchies, no "us versus them", I just want to say thank you.

Photograph by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy