Today The Observer is publishing the MacTaggart lecture on independence that I've given at the Edinburgh TV Festival.

As you’ll see, it's a warning about the damage being done by politics and technology to trust in our society. It makes the case to establish the independence of the BBC, the most important source of shared information and ideas in this country, and I would argue, around the world.

All of us who work at The Observer are proud to work for a paper that George Orwell liked to call ‘the enemy of nonsense’.

This is an argument for what the enemies of nonsense need to do now.

We hope the new Observer is a place too for civilised disagreement. You may heartily disagree or passionately agree. Please do let me know what you think: MacTaggart@observer.co.uk

When my grandmother died, she left me her typewriter. It’s an old Erika made by Seidel and Naumann in Dresden. And it sits on a shelf by my desk at home. My family were German Jews living in Berlin and my grandmother, a strong-willed woman, had wanted to be a journalist. Just as she was getting started, the Nazis took power and, almost as soon as they did, they barred Jews from working in the press. So, you can imagine, the typewriter feels like quite an inheritance – there to remind me how fortunate I am to work as a journalist and like a question in itself, as if to say: if you have access to the ink, what are you going to do with it?

My grandparents escaped Germany in the 1930s and came to the UK. Elsie, my grandmother, became a tour guide. She led coaches round the country; she sat in the front of the bus, smoking 80 Silk Cut a day and told German tourists the stories of these islands, her own punchy lecture on British values – democracy and freedom of speech, rule of law and fair play.

The first time I came to Edinburgh, it was with her. I was in my early teens and she had brought me along to see the sights and carry the tourists’ bags in and out from the coach. I can’t think what Elsie would think of the privilege this is, to be back in Edinburgh again today, delivering the MacTaggart in its 50th year to a room of people who have the freedom to tell stories and voice those values to the world. But I can imagine what, in her heavily accented way, she would want to say. So, let me get straight to the point.

While I have been writing this MacTaggart Lecture, the typewriter has come to represent something else. It’s become a symbol of the fear I have for the age we’re in, the fear that politics and technology are doing untold damage to trust in the world. On the one hand, politicians are trying to control or cancel the media, particularly news. On the other, AI is beginning to lay waste to the economics of information, while also remaking the job of story-tellers. What then for the person at the typewriter – for the reporters of news, the programme makers and the creators of culture?

A shared understanding of what’s true is disappearing before our eyes. We’re more divided, more certain we’re right, more suspicious of the motives of others. Large numbers of people are giving up on the idea of facts, going with their gut on science and medicine, denying climate change, some are getting the measles. More people are paranoid, prone to conspiracy theories, convinced that the ends justify the means.

A grimly familiar past feels dangerously close. An unrecognisable future is coming at us frighteningly fast.

We live in worried times, when fears stretch well beyond TV: can the market economy work for people? Will technology destroy more than it creates? Can democracy fix the problems we face?

But the media, most of all television, is not a bystander. We have the power to help mend much of what’s broken. There are many things to be done. This evening, I’m going to focus, largely, on one.

The BBC is the most important source of information in this country and, I’d argue, around the world; it is the best defence of truth and trust against the lies of dictators and demagogues; it’s what sets the UK apart both from propagandists in the likes of China and Russia and the shouting match in the US that is doing such damage to cohesion and democracy. This evening, I’m going to make the case that if we want to build confidence in shared facts and respect for the truth we need to establish the independence of the BBC. And I’ll try to set out how: to put it beyond the reach of politicians, to resource it properly and to open it up.

It’s time to choose if we want to keep chipping away at it or double down on it. If we are, to coin a phrase, traitors or faithfuls. When the government established the independence of the Bank of England in 1997, it put confidence in the central institution of the economy ahead of politics; the government today can and should do the same for the shared institution in our society by giving real independence to the BBC.

At this point, I should warn you that I once gave a speech and Jimmy Tarbuck came up to me afterwards to complain that it was too serious. I fear he won’t like this one – and he probably won’t be the only one.

The MacTaggart lecture has, I realise, been delivered by all kinds of people – playwrights and presenters, comedians and filmstars. The Roy family have each had a go: Logan, Kendall and Shiv, as ever, to clean up the mess. A programme-maker, a government policymaker, a TV executive, a visionary and a troublemaker – and that was just the year John Birt did it.

I’m not those things, I’m a journalist, not an insider on the world of television now, but, forgive the plug, an observer. I’m afraid I’m going to talk about news, it’s what I know. Happily, I’m aware from my days covering the MacTaggart as an FT reporter, what matters isn’t what’s said in this room, but in the post-match analysis in the bar. Perhaps we can get Gary to host it.

The TikTok video version of this year’s MacTaggart goes something like this: if you’re a viewer, you can’t believe your luck, it’s an all you can eat buffet of tasty TV on all kinds of screen; if you’re in the business, it feels like everyone’s on Mounjaro, the commissioners have lost their appetites and their libido – perhaps not just metaphorically. And, in news, already the most uneconomic of the food trucks in TV, there’s bickering over whether to serve high fibre or the ultra-processed foods the kids like, while fighting each other over the horrors in the world around us.

The bigger picture is a world being remade by technology and politics. Generative AI is already doing so much better and faster, we all use it or will want to use it. It’s exciting – and terrifying. When it comes to technology, we should know by now not to fear what we fear, but what we want. AI is going to replace plenty of jobs and cut loads of costs; it will reprice the entertainment business and rewire the information economy. In news, it will more or less end the links business model – referrals from search to stories – with devastating consequences for newsrooms that depend on either advertising or subscriptions; Facebook brought us post-truth, ChatGPT might well mean post-journalism.

George Orwell

In the US, Donald Trump has normalised political interference in the media. He has intimidated the commercial media, incentivised self-censorship and defunded public service broadcasters. We’d be very naive to think something similar can’t happen here.

The largest cohort of Americans – 36% – say they have no trust in the media at all; as it happens, the same percentage believe the 2020 election was stolen. Donald Trump won a second term with the support of 32% of eligible American voters. As of just over a year ago, more than half of Americans believe there was a second gunman in the assassination of John F Kennedy and nearly one in five thinks the moon landings were faked and staged in Arizona. Just over 40% of people think the following statement is definitely or probably true: “Regardless of who is officially in charge of the government and other organisations, there is a single group of people who secretly control events and rule the world together.” And truth decay has consequences. If you want the preconditions for nativism and racism, antisemitism and Islamophobia, cynicism and selfishness, distrust of professionals, experts and authority, the rise of vandalism, democratic backsliding, corruption, communal division and vigilantism, it’s in the growing suspicion that nothing we’re told is true.

In response, there are many things that need doing. We need to set the terms for the streamers, the platforms and the tech bros who have been buying up the biggest names in news and television, who own the bots that will generate more content than ever. This is where the biggest challenges to truth and trust now lie. Streamers and platforms like Youtube are treated as if they don’t have the responsibilities that TV has, as if they don’t have requirements to promote news or give prominence to local, educational or practical content. The principles that applied to television that enables a cohesive society and a competitive industry should surely apply to them. The same, only more so, applies to AI. We’re set to repeat the mistake of the first internet generation, waiting, watching and hoping for the best. For the first time in history, the most popular source of information is not going to be human. AI will soon be able to create limitless synthetic data, billions of internets of words and pictures. A machine is behind the typewriter.

Essential as those things are, this is not an away day for regulators. It’s a festival to talk about television.

When John McGrath, the playwright, gave the first lecture in honour of James MacTaggart, he was pretty bleak: TV, he said, was neglected, limited and “impotent - its style a matter of pretty pictures”. It was, he said, like listening to “a symphony over the telephone”. Heaven knows what he’d make of us watching it over the telephone. But the fact is that, today, the real world is on TV. Television has confounded the doomsayers. Drama is living through a magical age of realism. We understand each other so much better than we did in 1975, thanks in no small part to reality TV. And the TV screen is so much more accessible to anyone with something to say – in that sense, more real, more democratic. Morecambe and Wise invited Diana Rigg, Des O’Connor and Pan’s People onto the Christmas Special on the BBC fifty years ago; Bernard Delfont chose the line-up for the Royal Variety Performance on ITV. Today, the Sidemen didn’t need to get chosen by the channels to earn a bigger audience on Youtube. TV is the most influential – and enjoyable - mirror of our times.

It is also the most powerful cultural force in our lives and the most creative force in our culture. The film studios have largely given up on comic or satirical films, instead preferring remakes, franchises, spin-offs. TV still prizes the new idea, it’s where original story-telling happens these days, it’s still what we all talk about. And, for that reason, it’s the screen, whether in the home or in the hand, that politicians want to control, that’s where the resistance, polemical and, better still, satirical happens. TV is the most interesting and important medium in the world today. And, while we have a wild ride ahead of us, it will be for years to come.

Of course, it doesn’t feel that way. Television is being violently disrupted and is increasingly polarised. If you are a writer or producer, you’re being told there’s no money or you’re waiting for a green light that never comes. If you’re working at a commercial broadcaster, you can’t commission half of what you want, because the TV ad market has migrated to social media. If you’re a PSB, you worry that you can’t afford the price of talent given the competition from streamers. Then, if you’re a streamer, you fear you’re in an unwinnable arms race with other streamers chasing audiences struggling to afford the pricey subscriptions. If you’re a YouTube talent with more viewers than a nightly news show, you still can’t make the economics work. If you’re a YouTube executive, you’ve got a creeping anxiety that ChatGPT is going to kill off search and, with it, the Google goose that lays the golden egg.

In other words, if you’re in the entertainment business you’re thinking this doesn’t feel like the golden age, if it ever did, it feels like The Last of Us: we’re just trying to survive as the fungus of new things eats us alive.

If it’s any comfort, it feels worse in news. The audience is divided, advertising is deserting it, there’s an exponential increase in AI generated content and, with it, a new, seemingly unwinnable contest for attention.

At the same time, newsrooms are in a furious argument with ourselves over the coverage of Israel and Gaza. What’s happening there is heart-breaking; it’s no surprise that it’s the cause of such painful divisions between people, it’s very hard to view dispassionately. This is true for all media organisations and, as we’ve seen this year, particularly the BBC: it is about as difficult as it gets in news.

The hiring and firing of the editor-in-chief of the country’s leading newsroom and cultural organisation should not be the job of a politician. It’s chilling.

The hiring and firing of the editor-in-chief of the country’s leading newsroom and cultural organisation should not be the job of a politician. It’s chilling.

This summer, Lisa Nandy has weighed in. The Culture Secretary’s office insists she did not explicitly ask Samir Shah, the BBC Chair, to deliver up the D-G’s resignation after the Bob Vylan death chants at Glastonbury were streamed on BBC iPlayer. But people inside the BBC were left in no doubt that was the message. The place became paranoid about how the BBC itself would cover the story; people around him thought the political pressure would be too much. Whatever your view of the hate speech vs freedom of speech issues, an overbearing government minister doesn’t help anyone. The hiring and firing of the editor-in-chief of the country’s leading newsroom and cultural organisation should not be the job of a politician. It’s chilling.

I am Jewish, proudly so. I’m proud, too, to have worked for the most important news organisation in the world. The BBC is not institutionally anti-semitic. It’s untrue to say it is. It’s also unhelpful – much better to correct the mistakes and address the judgment calls that have been wrong, than smear the institution, impugn the character of all the people who work there and, potentially, undermine journalists in the field working in the most difficult and dangerous of conditions.

The BBC has, for sure, made mistakes. I speak from experience – in my time there, I made some serious ones. And it’s fair to say that the BBC can be much too slow to correct them and, when it does, it can sometimes overdo it, sometimes stand on its dignity. For what it’s worth, I thought the BBC was wrong not to use the word terrorist for the attacks of October 7th; journalists shouldn’t censor words, but use them accurately. I’m in the camp that believes a brilliant football pundit like Gary Lineker should be able to have views as a citizen, as well as a job as a BBC broadcaster. And while there’s been plenty of comment on current affairs programmes on Gaza – what the BBC has run and what it’s pulled – I’ll spare you my views, because I’m well aware that it’s easier to judge the process with hindsight or sound off when you’re outside it.

Gary Lineker

It’s different when you’re in it. In fact, I might well have made or agreed to many of those decisions if I were still at the BBC. Because the BBC requires a level of political judgment in its management that is unlike any other media organisation.

This is not, by the way, a comment on the director-general. It's a hell of a job and I wouldn't want to do it. Anyone who cares about the BBC should be grateful to Tim Davie: he has hired brilliant people and let them loose to make fantastic programmes, he has transformed the business in building Studios, he is spreading its footprint across the country, he is a quietly determined tech evangelist when others are putting their heads in the sand and, with a resilience that is selfless, he acts as a human shield through crises and scandals that have not been of his making, but that he has answered for honourably and openly.

But the point I want to make is that while mistakes will always happen, the BBC has to second-guess the consequences of those mistakes, because it serves the public, but answers to politicians.

The BBC chair is appointed, in effect, by the Prime Minister. Richard Sharp was Boris Johnson’s choice; Marmaduke Hussey was Margaret Thatcher’s, Gavyn Davies was Tony Blair’s. Half of the board’s non-executive directors are chosen by the government: when Emily Maitlis was here, she pointed out that Robbie Gibb, No. 10’s former spin doctor, is on the board and keenly involved in editorial oversight; he still is.

The Chancellor sets the budget. The licence fee settlement is negotiated with the Department for Culture Media and Sport, but, when it comes to it, it’s decided in No 10 and No 11; the most important newsroom in the country operates in the knowledge that the editorial budget is, ultimately, set in Downing Street. After he left government, George Osborne came to talk to BBC leadership – I was no longer at the BBC, so not in the room – but I’m told he said that he had been “surprised” to discover the power the Chancellor had over the BBC. It was, he said, essentially unchecked.

The BBC matters beyond its own output. Michael Grade famously said here that it’s “the BBC which keeps us honest”. It’s also the BBC which keeps us together. Without anything that keeps you together, there is no floor on the decay of truth.

The BBC matters beyond its own output. Michael Grade famously said here that it’s “the BBC which keeps us honest”. It’s also the BBC which keeps us together. Without anything that keeps you together, there is no floor on the decay of truth.

Allow me a trip back into the world of newspapers. When I became editor of the Times, I took William Rees-Mogg, the former editor, for lunch. He told me the most important thing for an editor was never to get too close to the government, never, in his words, walk into No 10 wanting something in return. Geoffrey Dawson, the Times’ editor in the 1930s, had got too close to the Chamberlain government and backed appeasement. When William became editor in 1967, the paper was still trying to get over it.

The DG and the chair of the BBC always have an eye to charter renewal and the licence fee settlement. As they should do. It determines the work and the revenue of the BBC. As 2027 approaches, the BBC will move into Charter renewal mode.

For good reason: its survival is at stake.

This is true constitutionally. It’s extraordinary, when you think about it, that if Parliament chooses not to renew the Royal Charter in 2027, the BBC will cease to exist; this, by the way, is different from universities or other organisations that are established by Charter in perpetuity. The BBC, which politicians can’t help but keep on a leash, is, in effect, on a 10-year contract.

And it’s true politically. Donald Trump has, as you’ll have seen, cut $1.1bn from the funding of public broadcasters in the US, killing off the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, forcing the closure of many local stations and hacking away at NPR and PBS. Internationally, the Trump administration has been more sweeping still, summarily sacking staff and closing down the Voice of America, Radio Free Asia and Radio Free Europe. It’s a popular move, backed by the majority in the House of Representatives, turning into government policy the MAGA politics of bashing the mainstream media. Donald Trump has driven a partisan divide in trust: 54% of Democrats trust the media; it’s just 12% of Republicans.

A similar partisan gap is opening up here: 32% of Labour voters trust the media, 13% of Reform voters. The Reform Party’s manifesto commitment on the BBC is this: “The out-of-touch wasteful BBC is institutionally biased. The TV licence is taxation without representation. We will scrap it. In a world of on-demand TV, people should be free to choose.” In other words, the one-time reality TV star who leads Reform has some bracing reality in store for TV. It’s recklessly complacent to ignore it. What’s happened in the US is, as likely as not, going to happen here. We have to address this now.

The BBC matters beyond its own output. Michael Grade famously said here that it’s “the BBC which keeps us honest”. It’s also the BBC which keeps us together. Without anything that keeps you together, there is no floor on the decay of truth. The BBC is a touchstone, it belongs to all of us. Even in our most furious arguments with the BBC about its subjects and stories, we reinforce our belief that common narratives and agreed facts matter, in the reality of objective truth, the importance of a sense of proportion, the openness to differences of opinion.

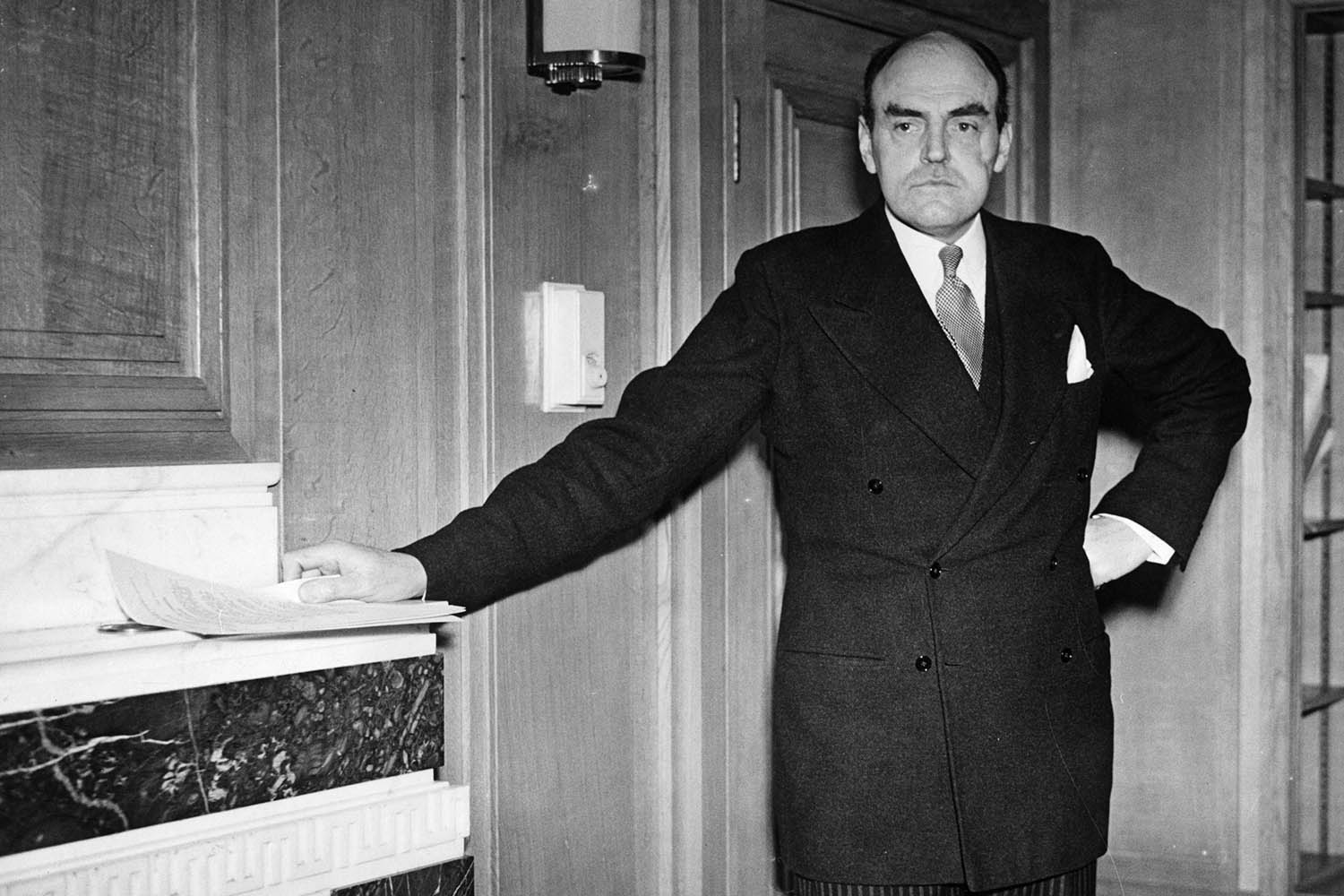

John Reith

Nearly one hundred years ago, John Reith fended off a government attempt to take control of the BBC. At the height of the General Strike in 1926, Winston Churchill, then Chancellor, sought to commandeer the BBC; Reith lobbied Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister, and saw off Churchill’s attempt to make it a mouthpiece of government. Independence has been a foundational principle, accepted by politicians, relied upon by programme makers and expected by the public, ever since. Margaret Thatcher once told David Dimbleby that “every time I try to do anything about the BBC, people come out of the woodwork to defend it”. We like to think there’s a bipartisan commitment to the BBC. But the reality is not like that any more. It’s not a bipartisan country; there’s not the same commitment.

Political interference – and the perception of a political presence looming over the BBC – is a problem, one that we’ve got too accustomed to. And it looks likely to get worse. We need to get on with putting the country’s most important editorial and creative organisation beyond the reach of politicians now.

To depoliticise the BBC means changing how appointments are made and budgets are set. The BBC chair and board of directors should be chosen, not by the Prime Minister, but by the board itself and then, like other such organisations, with the approval of Ofcom. The BBC will attract more and better people to apply for those jobs if they don’t feel like the appointment is a political stitch-up. The Charter should be open-ended. And the licence fee – or any future funding arrangement – should not be decided behind closed doors by the Culture Secretary and the Chancellor, but, as in Germany, set transparently and rationally by an independent commission that impartially advises Government and is scrutinised by Parliament.

The BBC, of course, needs to be democratically accountable. Painful as it can be when you work there, the fact that it's subject to the extremely watchful eye of the press is one of its strengths. In the pages of the papers I’ve worked for, both the FT and the Times, we’ve been critical of the BBC. But accountability and scrutiny are different from control, different from politicians with a grip on the purse strings and the appointment of the people at the top.

For more than a decade now, politicians have talked pretty about the BBC, then piled on obligations and chipped away at its funding: the deals on over-75s, World Service, loosening up on non-payment of the licence fee means the BBC’s funding has been in decline in real terms for more than a decade. Cost-cutting has become part of the culture of the place. But the BBC’s best moves – creating the iPlayer, building Media City in Salford – have come when it’s had the budget to do new things, not just kill off old ones.

Trust is what underpins the BBC. The suspicion that the BBC is captive to one worldview erodes that trust; openness to others can rebuild it.

Trust is what underpins the BBC. The suspicion that the BBC is captive to one worldview erodes that trust; openness to others can rebuild it.

BBC independence means giving it the resources it needs. Not freezing its funding yet again, but doubling down. We’re at the beginning of a new information age, if we want it to be truly creative, innovative and competitive globally, we can’t short-change the BBC again. We need, surely, to be thinking about a mix of funding that gets closer to doubling its resources. Because, obviously, given the cost of living, that’s not going to happen just through the licence fee. Over five years, nearly 2.5m households have dropped out of paying the licence fee, so this needs fixing: it’s expensive and unfair on those who pay. If we believe in the universality of the BBC, we need to return to the principle in some form or other that every household pays. But, happily, the licence fee is not the only source of income: the BBC is building an impressive business in Studios; it has the potential to earn more for its content on streamers and platforms; it should lead the way in striking deals with generative AI companies on meaningful pricing of its reliable, ceaselessly renewed library of content, something that would help set the terms for other UK news and media companies that don’t get a hearing from the new generation of tech giants.

Today, the UK has a renewed commitment to global security. It’s time, then, for a proper funding deal for the BBC World Service – the UK’s most powerful expression of soft power just as US public media is pulling back. A side note: the World Service’s weekly audience is bigger than the entire subscription base of Netflix, which has an exciting mantra “to entertain the world” but not a patch on the BBC’s “nation shall speak peace unto nation”. A properly funded World Service could reach a billion in the decade to come, an ambition that should appeal to all in this country and a contribution to fighting misinformation worldwide.

Perhaps the biggest buttress to independence is openness. Trust is what underpins the BBC. The suspicion that the BBC is captive to one worldview erodes that trust; openness to others can rebuild it.

The BBC has long been indispensable to the UK’s creative industries, sustaining skills and giving people a break they wouldn’t have got elsewhere. But it’s much patchier, sometimes positively resistant, when it comes to working with others in news and current affairs. There’s an assistant editor on the Today programme who chooses which stories from the papers to plug at 6.10 and 7.40. There’s the Local Democracy Reporters Programme which we set up to work with local newsrooms, providing money and reach to their journalism. The BBC has started choosing a few podcasts to run on Sounds.

But why can some editions of Panorama be made by independents, but no editions of Newsnight? It’s illogical, as if it’s somehow alright to open up a fraction of current affairs to independents but hold the line on news. I understand why this thinking holds. Traditionally, the BBC has felt that News is too important and too core to its mission to be opened up. But, if the lesson of recent years is that it needs to head off accusations of narrowness in its agenda and its approach which are corrosive of public trust, then no BBC division needs openness more than News which, paradoxically, has the least of it.

So, imagine a BBC that thinks of itself more as the People’s Platform as well as a Public Service Broadcaster, one that’s home to more varied thinking but holds true to standards of truth and accuracy, diversity of opinion and fair treatment of people in the news. What might that involve?

One, it would open up to outside producers to compete to produce news and current affairs programmes. Making programmes like Newsnight open to competition and inviting offers for new shows would do for the BBC’s mission to inform what it has long done for entertainment – namely bring in fresh ideas and different people, encourage the BBC itself to be more innovative and exciting, spread the economic benefits of the BBC’s strength to other parts of the journalism business in the UK.

Thomas Jefferson

Two, there are things BBC News can’t and shouldn’t do, such as take sides, have opinions, champion causes; but there is public service journalism that other newsrooms can do. So, if the BBC were to set aside a fund for independent reporting in the public interest, it really could help deal with the UK’s own news deserts and information inequality.

And, three, it could serve as the equivalent of a digital newsstand, a place where you could access a much wider range of voices, where you could give reach to new providers as they get going, where you could broaden what qualifies as news to include more of what’s happening in the world of food, fashion, things people love.

The idea of an open platform would invite the BBC to think not just about how it informs and entertains, but how it educates too – how it could partner with the Open University, how it might work with AI developers to provide a BBC GPT, one that enables people to ask questions without handing over every last detail of what’s on their minds to US tech corporations that have proved obstinately unaccountable in the UK. This is about more than the BBC, it’s a national investment in our future that will come back to reap multi-platform rewards that an investment in no other UK organisation can.

Impartiality is essential to the BBC. It’s also tricky, as most people don’t know what it is, those who do are often the ones who define it and it’s commonly abused by politicians to insert themselves into the conversation about what should be covered by the BBC and how. But an open BBC would do a good deal for impartiality. It would be a BBC that’s impartial within its own output and a BBC that is impartial across the outside views it hosts.

Thomas Jefferson made the best ever argument for independent journalism: “The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people…Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

Last year, Tortoise, the slow news start-up that I left the BBC to found in 2018, bought The Observer, the world’s oldest Sunday newspaper founded in 1791. Not everyone, it’s fair to say, loved the idea of it leaving The Guardian, which had been its home for 30 years. We believe, of course, that we have bought much more than a newspaper. The Observer is a brand; better still, it’s a promise. The Observer was founded with a pledge to share “every species of knowledge that may conduce to the happiness of society”. Not far from John Reith’s belief that the BBC’s job is “to bring the best of everything into the greatest number of homes”. George Orwell, who, after leaving the BBC, wrote for The Observer, liked to call it “the enemy of nonsense”. Media institutions that last know what they’re for.

And also, for whom. The BBC, unlike all the other great powers in the world of information and entertainment, is for everyone.

One morning when I was running BBC News, a story cropped up on the newslist at the 9 o’clock meeting. Vinyl was back, sales of records were apparently soaring. So we thought it would be fun to send a reporter and a camera down Oxford Street to ask people why. The crew stopped a couple of young people, held up a record and said: “Hi, we’re from the BBC Six O’Clock News, do you know what this is?” The teenager replied: “Yes, it’s a record.” Then, paused. “What’s the Six O’Clock News?”

Joni Mitchell

You might take an upbeat view of that moment: it’s exciting to think that there’s so much to play for and it shows that you get the best stories sending reporters out to find out what’s really going on. But it’s also warning of a world without a common sense of our story, without a shared understanding of the value of facts in an argument, without a place that connects us across generations and continents, one where we find ourselves sitting in the dark, humming those words that Joni Mitchell laid down on vinyl 50 odd years ago: “Don’t it always seem to go, you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.”

To be the enemies of nonsense, we must act now.

To be the enemies of nonsense, we must act now.

The world is not as we were promised, either by the politicians or the tech evangelists. It’s a world where everyone has a typewriter, but fewer are seen or heard. The most powerful man in the world types out soundbites, in caps, regardless of fact; the richest man is more powerful than any television channel, typing unchecked to an audience of 200 million people instantaneously, weighing in behind politicians and parties in places he barely knows.

We in this room are lucky enough to have access to what a century ago was the typewriter; today it's the screen. TV, in all its forms, is the means of communicating most meaningfully to the largest number of people. The biggest and best typewriter of all in this country is the BBC; my hope this evening has been to make the case for why and how we take care of it.

If we wait to see what the future has in store for us, I fear that the recent past can give us the answer already. Bystanding is surrender. We can choose the society we live in; or we can choose not to choose. To be the enemies of nonsense, we must act now.

Thank you.

Photographs Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy