What will historians record about 2025? It won’t all be bad. China has installed 250GW of solar power in the first half of the year alone – twice as much as the rest of the world combined. Capital investment in AI in the US has reached a staggering $500bn. Nuclear fusion has achieved a significant breakthrough.

But in a world with more resources to do more good than at any time in human history, the landscape is charred with damage.

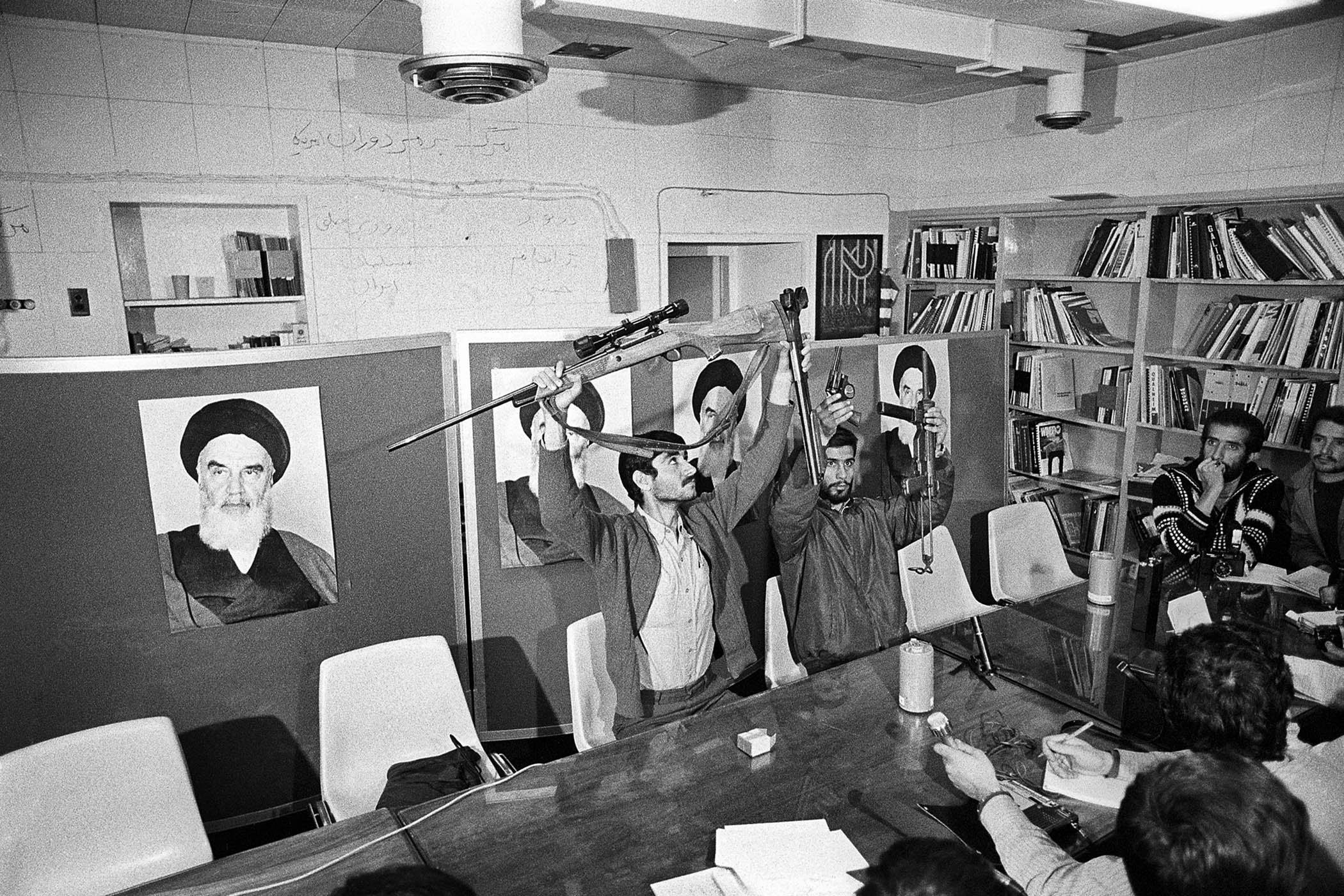

There are 60 active conflicts. The World Bank has revised up the number of people living in extreme poverty (less than $3 a day) to 830m. The Varieties of Democracy project says that for the first time in 20 years there are more autocracies than democracies. The UNHCR says there are 125 million refugees and internally displaced people. Famine has been recorded in Gaza and Sudan, with four other countries at imminent risk. Carbon emissions have breached last year’s record and the target of limiting the rise in average global temperature to 1.5C has been torched.

And alongside damage there is danger. Climate change, AI, pandemics and the nuclear arms race all run the risk of crossing tipping points.

How did this happen? Undoubtedly, policy mistakes spurred inequality and instability. But the changes that have ruptured the global order are more structural, and when combined create today’s “polycrisis”.

First, as a consequence of a more connected world, global risks have risen exponentially, far outstripping the ability of global institutions to manage them.

The Covid pandemic provides a telling example. The climate crisis even more so. So too the refugee crisis. In each case, international cooperation has been too weak to meet the challenges. Bloat and power in international institutions have been blamed, but it is their weakness, not their strength, that has been exposed.

While globalisation is not new, a hyper-connected world is. And it has emerged without anyone in charge. This is the second big change. The 10 Brics countries now account for one third of global GDP and half of the global population. In addition, countries as diverse as UAE, Turkey and Indonesia have achieved a quantum shift in their economic development, and are now putting their power to geopolitical use.

America’s share of global GDP has not changed. In 1990, it accounted for 25% of global GDP, and it continues to do so today. But the rest of the G7 group of leading industrialised democracies (including the UK) has seen its share of global income fall from 42% to 18%.

The first two changes are being accelerated by a third – the technological revolution. The shift from an industrial age to a digital age has ripped up the social, economic and political contract.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

For all the debate about the impact of trade on manufacturing jobs in the industrialised world, it is clear that technological change has been a far bigger contributor to de-industrialisation. The stand-off between the US and China over semiconductors and rare earths – each side with a choke-hold on the other – is a stark example of what is at stake: both can threaten to halt key sectors of the other’s economy.

The challenge for open societies is fundamental. Yet hunkering down will not reverse these processes, because capital flows, refugee flows, even trade flows are rising, not falling, and technological change is accelerating.

We need to look for stabilising buoys in this stormy sea. Since the second world war, this has been provided by the idea of “the west”, defined in the Atlantic Charter signed by Churchill and Roosevelt in Newfoundland in 1941. Its central tenets were that the postwar order should learn the lessons of the period after the first world war; above all, that nations should be able to define their own futures and not be subjugated by the powerful; that trade should be open and free; that human rights should be meaningful and equal; and that the rule of law, not the rule of the jungle, should govern international affairs.

By the end of the cold war in 1990, these ideas seemed hegemonic. Not any more. Democracy is in retreat; mercantilism on the rise; multilateral institutions are weak and weakening. And we have to notice that the vice-president of the United States, echoed by many on the right, says that “there is something about western liberalism that seems almost suicidal or at least socially parasitic”.

I don’t agree with those who say that the Trump administration has no ideology. It begins, as President Trump put it in Warsaw in 2017, “with our minds, our wills and our souls”. The challenge is to the core idea of the west.

Far from lauding the checks and balances of liberal democracy, the commitments to minority rights and human rights, the promotion of regulated trade, the belief in multilateral international organisation, the administration sees these as the root of the west’s decline. It is actually Putin’s argument as well.

On these issues the west is riven. We are also divided on foreign policy questions, from Russia to climate to global health to Gaza. And watch out on China. I was in Beijing in October. There are serious dangers in a confrontation between the US and China. But Europeans must also beware the dangers if Washington and Beijing come to an agreement that leaves Europe caught in a pincer.

We have to recover the moral clarity and political vision of what we stand for

We have to recover the moral clarity and political vision of what we stand for

This leaves Britain facing double jeopardy – domestic and foreign. Austerity, Brexit and Covid have battered us, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made a pivot in foreign policy towards Asia seem naive. We are each £16,000 per year poorer than we would have been if we had sustained pre-2008 levels of economic growth.

We are out of the EU; America is tough and transactional; and the UN system in which we have a privileged position is in retreat. We don’t have the finance of Saudi Arabia, the European links of Germany, the demography of India or the regional sway of Turkey.

For countries like ours, the challenge is not to build a new world order, but to contribute to what the historian Adam Tooze calls “world ordering”. This means multiple “coalitions of the willing” that push back against impunity.

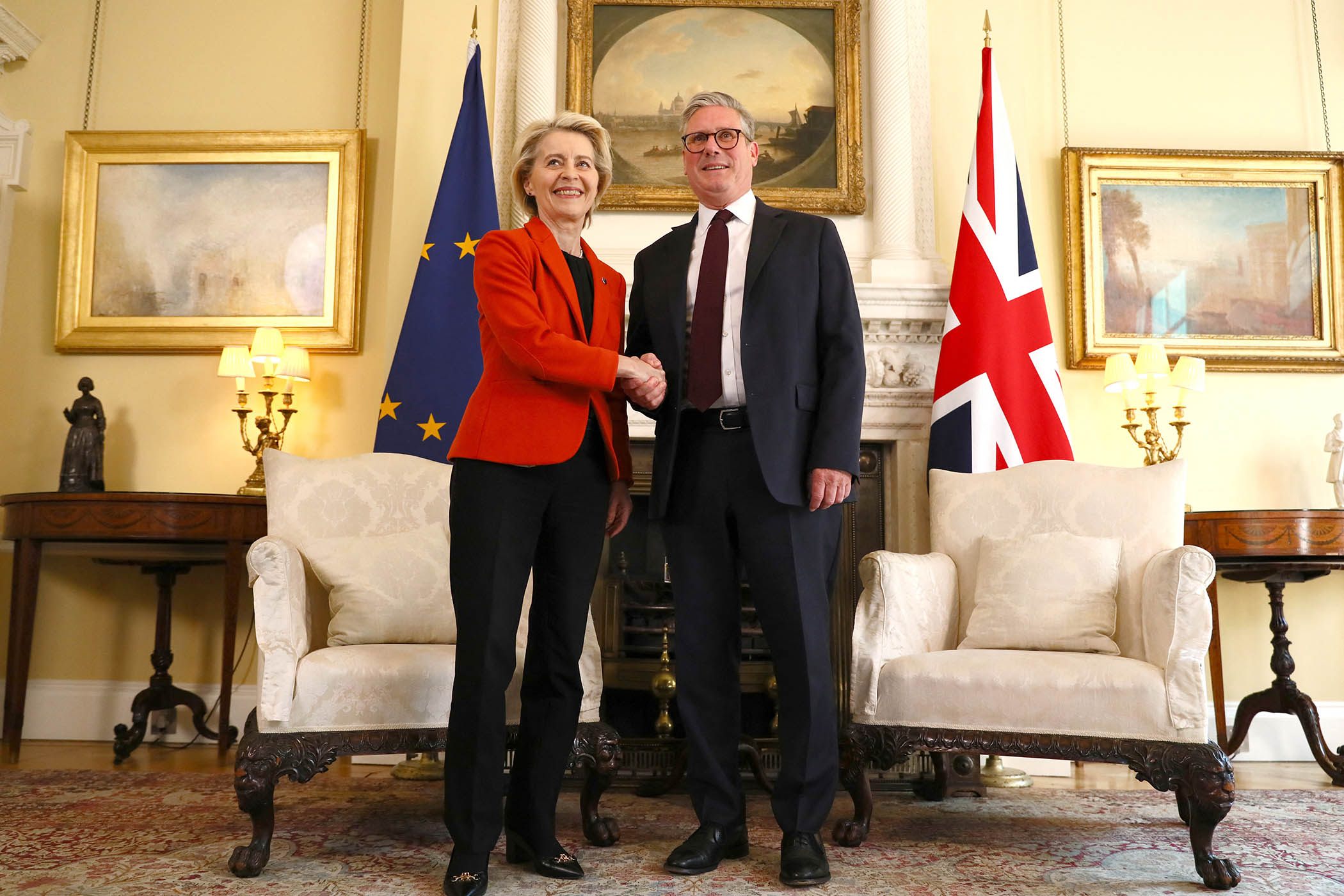

That starts with the rest of Europe, where our interests and values are aligned but cooperation is sabotaged by Brexit. The economic questions are pressing – a commitment to regulatory alignment for manufactured goods has been estimated to be worth more than a 1% boost to GDP – but there are many other areas where we need greater cooperation.

For example, the proposed €800bn “European defence mechanism” would issue long-dated bonds to pay for increased defence spending, and would be off the balance sheet at least until procurement. This plan should be in the “essential” rather than the “too difficult” box. On rare earth minerals, where China is overwhelmingly dominant, the EU’s approach is more muscular than the UK’s, and we have shared interests in closer cooperation. On international aid, we should be forging common effort and common funds.

The new multi-aligned world means we need alliances beyond Europe as well as, not instead of, with Europe. For that global role to be credible, the UK needs to be on the side of reform, for example suspending the UN Security Council veto in cases of mass atrocity, ensuring merit, not nationality, is the only criteria for UN jobs, and supporting a single, non-renewable seven-year term for the UN secretary-general.

Eighty years ago, George Kennan ended his famous Long Telegram from Moscow by saying the greatest danger is that we allow ourselves to become like those with whom we are competing. Today, the task is not to seek to restore lost dominance, but to recover the moral clarity and political vision of who we are and what we stand for.

As democracies and their politicians are tempted down a path that rejects pluralism, harasses opponents, demonises refugees, declares emergencies, opts out of international agreements and laws and attacks the judicial system – all features of the Soviet system – this is surely the ultimate role reversal in the world today, and one that we need to fight at all costs.

This article is extracted from the 2025 Isaiah Berlin Lecture to be delivered today. David Miliband was foreign secretary from 2007-2010

Photography by Alishia Abodunde/Pool/AFP via Getty Images