Keir Starmer can be as impenetrable as the front door behind which he now lives. This is made of reinforced steel, has a sealed letterbox, and neither a handle nor a key to open it from the outside. Both he and the famous entrance to 10 Downing Street are, however, unlocked from within.

We are sitting in his study upstairs in Downing Street. He prefers it here because there’s more sunlight and it is “a bit more out the way” than his darker office in the day-to-day tumult of government on the ground floor below.

On a previous visit, we’d had coffee in a room where there was an oil painting of Margaret Thatcher that Starmer said he didn’t like. When he had it taken down a few days later, foam-flecked outrage flew at him from her fanbase. But his objection to the portrait had less to do with Thatcher in particular than with politics in general: he didn’t want any predecessor staring down on him. Unlike those who have tried to place their “visions” within the historical arc of ideas in No 10, he has never been interested in a Starmer-ism and his identity is more likely located in the family clutter of the flat above No 11.

Can the Starmers have a normal life there? “Up to a point.” He generally avoids having meetings or drinks with colleagues in the flat so that “it’s just me, [my wife] Vic and the kids”. Do his children bring friends round? “Yep. But they were a bit reluctant to start with because it’s sort of weird to say: ‘Come over for a sleepover but you’ll need your passport; a man with a gun will check your bag and X-ray your teddy,’” he says.

They have a new cat, Prince, who is kept indoors. But Starmer has tried to ensure their old one, JoJo, can still roam free. Early efforts to have a catflap installed were frustrated because their back door, like all those in the building, has very solid anti-ballistic defences. But now he’s found “a workaround” for the problem.

“I’ve got to show you this,” he says, getting up and pointing to a half-open window in the family flat. Beneath it is a box that he explains is “a sort of landing patch leading to that zig-zag wooden contraption we’ve built so JoJo can get to the bottom and do his stuff”. Like an escape route then? The prime minister smiles. Fancy one yourself? He sits back down.

Starmer fought hard to get through the Downing Street door and, in case anyone doubts it, makes clear he’s in no hurry to leave. Before 5 July last year, he had only been inside here once – more than a decade ago, before he entered politics – but now found himself in this maze of corridors, whispered briefings and intrigue.

August: Starmer makes his ‘gloomy speech’ at No 10 during summer recess

“This can be a hard place to work,” he admits. “Sometimes you can’t think out loud here without people reading about it the next day.”

After a year in power, has being prime minister proved harder than he expected?

“It was more that the damage left behind by the last government was genuinely worse than I had imagined,” he says, cautiously. “We had to do a lot of tough stuff early.” Even so, Starmer recognises that people had also expected more than just “tough stuff” from a new government. He accepts his gloomy speech in the Downing Street garden last summer, where he warned “things will get worse before they get better”, was a mistake. It “squeezed the hope out”, he says. “We were so determined to show how bad it was that we forgot people wanted something to look forward to as well.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The bigger puzzle, however, is why a prime minister so clearly aware of how shallow the water in politics can be has allowed his government to spend so much of the past year face down in it.

In the first few weeks after the election, office politics inside Downing Street sometimes seemed elevated above any other priority. There was an extraordinary amount of anonymous briefing aimed at his then chief-of-staff Sue Gray, who had swiftly amassed enemies among both civil servants and his political advisers.

Some of the claims made about Gray, such as her banning political advisers from using government teabags, were untrue or exaggerated. And many of the biggest early errors, including the Treasury’s decision to scrap winter fuel payments for most pensioners, were not her fault.

Yet, even before his government was 100 days old, the woman who had been supposed to make it all work was removed and replaced by the Labour election strategist Morgan McSweeney. Starmer insists he never fell out with Gray and is clearly reluctant to reopen it all now. “Not everyone thought it was a good idea when I appointed her,” he says, with some ice in his voice. “It was my call, my judgment, my decision, and I got that wrong. Sue wasn’t the right person for this job.”

His emotional temperature rises when he talks about the row over accepting expensive clothes for the election campaign and tickets to watch Arsenal and see Taylor Swift concerts with his family. He’s adamant this controversy shouldn’t have festered for weeks because no rules were broken, no public money was spent and no favours given in return. And, while critics said he didn’t understand politics enough to realise how bad it looked, he points out that “optics” are not the same as substance.

September: News breaks that Starmer accepted free tickets for football and concerts

Yet what really got under his skin was not that his own integrity had been questioned, but that sections of the media started calling his wife “Lady Victoria Sponger” because she had received about £5,000 worth of clothes. Looking back now, he admits: “Part of the problem is that I got emotionally involved. One thing I’m reasonably good at usually is staying calm. But when they dragged Vic into it through no fault of her own, that made me angry.”

And, in the pressure cooker of his first year as prime minister, that wouldn’t be the last instance of steam escaping from fiercely guarded emotions.

Leeds, January

Two large cars with tinted back windows drove slowly through the south side of Leeds before coming to a halt outside a small semi-detached house. The house did not usually get many visitors. But the grey-haired, casually dressed man who emerged from one of the vehicles did not look so out of place.

Starmer asked his armed police bodyguards to wait behind and opened the glass-fronted door. Once inside, he filled black bin liners with rotten food from the fridge and dirty clothes from the floor. Then the prime minister got to work cleaning the bathroom and toilet.

The house had belonged to his younger brother, Nick, who died on Boxing Day. Starmer had been up and down to Leeds, delaying the start of his first holiday in more than a year, so he could “sort what needs sorting”.

By January, any lingering excitement about the new Labour government had been replaced by a mixture of fascination and fear about the consequences of Donald Trump’s second election victory. As political leaders around the world turned their eyes to Washington before the presidential inauguration, Starmer had returned to Leeds on that private mission. “The previous day I had been taking calls on the future of European security and there I was, on my hands and knees with a brush scrubbing out the back of the bog,” he recalls now of that time. “That’s quite a good leveller.”

Couldn’t he just have got cleaners to sort the house out?

“No,” he says, “I didn’t want anyone else there. He was my brother – I didn’t want to let him down.”

Nick “hadn’t kept the place very clean”, explains Starmer, suddenly gulping for words before describing how “I was putting what he’d left of his life in a bag”. The prime minister forces himself back into his more familiar and less expressive form before continuing. “But – but – there you go, I suppose.”

Starmer is, of course, not the first person to hold this office who has suffered grief. But his emotion is telling. He had always been deeply protective of his brother, who was born with difficulties learning. There were, apparently, a few fights with other children when he heard Nick being insulted – and it’s still a bad idea to describe anyone as “thick” or “stupid” in the prime minister’s presence.

Over the decades, Starmer has learned to express his protective instincts in other ways, going to extraordinary lengths, for example, to keep his brother’s terminal cancer diagnosis a secret.

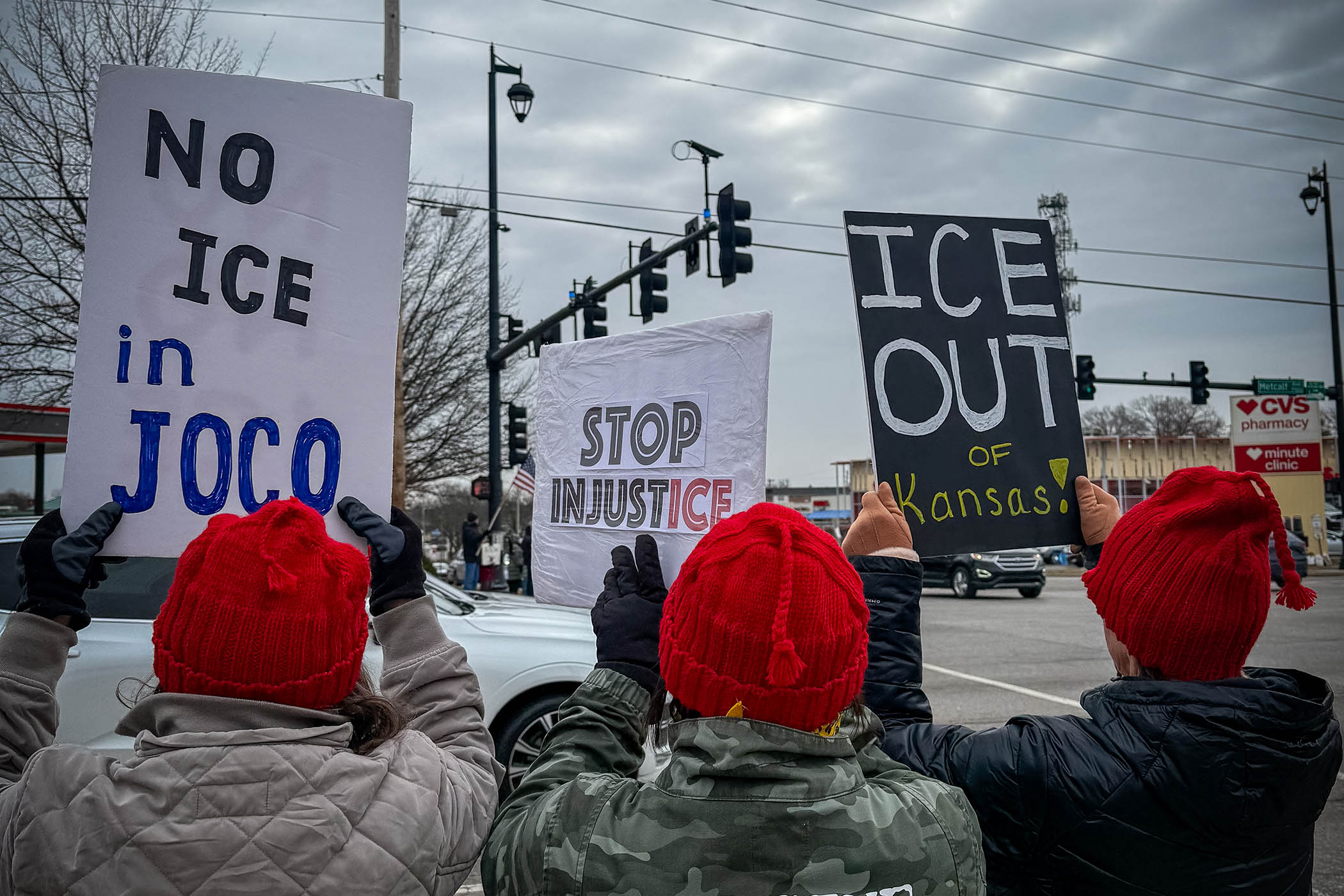

October: A protest against the government’s plan to cut winter fuel benefits

When I was writing my biography of him, Starmer told me of his brother’s “sort of nomadic existence” and his deep sadness that Nick was dying just when he had at last found somewhere permanent to live. Here was a human story that went to the heart of Starmer’s values and identity at a time when he was often being criticised for lacking both. But he didn’t want it known to voters, or anybody else.

During the election campaign last summer and after he entered Downing Street, he continued to visit his brother by slipping incognito through the back door into the hospital where he was being treated. He once told me that discussing Nick’s condition even in private felt “a bit violating”.

This capacity to keep intense feelings bottled up may stand him in good stead in a time when, he says, “global politics are more fragile than at any time in many years”. It helps explain why he had been so careful and cautious in his dealings with Trump. Before their White House meeting on 27 February, Starmer saw no point in loudly proclaiming positions when what matters is “actions not words”. He says: “We’re in a different world. We just have to deal with it.”

When I ask what it was like in the Oval Office, Starmer’s eyes slide sideways for just a moment. “Well, interesting,” he replies. “I signed the visitors’ book and then, before we had really started talking, Trump says: ‘Let’s get the press in’, and we’re conducting a bilateral in front of the media with him taking questions from literally anyone.”

What might have otherwise gone wrong was demonstrated the very next day, when Volodymyr Zelenskyy was goaded into a clash with Trump, before being ejected from the White House alone and empty-handed, like a failed contestant on The Apprentice.

In the hours afterwards, Starmer notably didn’t join other European leaders in posting condemnation of the US president on social media. Instead, pictures of Starmer locked in a warm embrace with the Ukrainian president when he arrived outside Downing Street the following evening were seen around the world.

“Normally, I would wait on the step to greet him,” Starmer says. “But I was really conscious that he’d left the White House on his own. That’s why I walked towards him and gave him a sort of hug. It’s also why I walked him out to the car at the end; I wanted him to know that you don’t leave my house on your own.”

The Observer Daily: the very best of our journalism, reviews and ideas – curated each day.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for free by clicking here.

Kentish Town, May

In the small hours of 12 May this year, there was a firebomb attack on the Starmer family home in Kentish Town. His sister-in-law, who had been renting the house since he became prime minister, was upstairs with her partner when the front door was set alight. “She happened to still be awake,” Starmer says, “so she heard the noise and got the fire brigade. But it could have been a different story.”

Before the election, he regarded that door as the gateway between what he called “real life” and “the slightly weird one” into which he had landed. “As soon as I walk through the door, I am just Dad,” he’d say. His home was a space preserved for family, where he could be the person he was before he entered politics and, perhaps, remind himself of why he had done so in the first place.

February: Starmer meets Donald Trump in the Oval Office

And, if those responsible for the arson attack probably didn’t realise how important Starmer’s front door was to how he viewed the world, setting it on fire had an immediate effect on politics.

The prime minister, who had arrived back from a three-day trip to Ukraine the night before, was due to unveil the government’s new immigration policy that morning. “It’s fair to say I wasn’t in the best state to make a big speech,” he says. “I was really, really worried. I almost said: ‘I won’t do the bloody press conference.’ Vic was really shaken up as, in truth, was I. It was just a case of reading the words out and getting through it somehow …” – his voice trails off – “… so I could get back to them.”

The prime minister’s words included a long section on the importance of having “fair rules” that “give shape to our values” and hold diverse nations such as Britain together. But then he went on to warn that without such rules, “we risk becoming an island of strangers”. To many ears, that sounded a lot like Enoch Powell’s infamous “rivers of blood” speech half a century earlier, when he said Britain’s white population would be “strangers in their own country”.

The left denounced his speech as “shameful” and warned Starmer was dancing to the populist Reform UK party’s tune. Starmer insists none of that is true: the speech was simply a mistake. “I wouldn’t have used those words if I had known they were, or even would be interpreted as an echo of Powell,” he says. “I had no idea – and my speechwriters didn’t know either,” he says. “But that particular phrase – no – it wasn’t right. I’ll give you the honest truth: I deeply regret using it.”

Emphasising he is not using the firebomb attack as an excuse and doesn’t blame his advisers or anyone else except himself for these mistakes, Starmer says he should have read through the speech properly and “held it up to the light a bit more”.

The prime minister also accepts there were “problems with the language” in his foreword to the policy document that said the record high numbers of immigrants entering the UK under the last government had done “incalculable damage” to the country. Although Starmer says the issue needed addressing because the party “became too distant from working-class people on things like immigration”, he accepts “this wasn’t the way to do it in this current environment”.

Perhaps the best proof that his words were accidental is that they stand out as an exception to how he has led his government since Labour’s defeat to Nigel Farage’s party in the Runcorn and Helsby byelection on 1 May.

May: The front door of the PM’s former London home after an arson attack

As with a previous defeat at the hands of Boris Johnson’s Tories in Hartlepool four years ago, the loss has had a cathartic effect on Starmer. “No leader moves forward seamlessly without making mistakes,” he says. “But if you look back at what happened in 2021, it was when I resolved we were never making the same mistake again. If there’s one thing about me, it’s that I learn.”

This is how he has always been most effective. Like someone crossing a minefield, he takes steps backwards, to the left and the right, before moving forward again. It may look inelegant or uninspiring, but it’s still probably the best way of getting to the other side. Starmer is never going to satisfy the demands of shouty social media with drama and big new ideas. Instead, he offers complexity and compromise. He makes mistakes, then finds a way that works better.

There has already been a U-turn on the winter fuel allowance and there are hints that the government may scrap the two-child benefit cap if the money can be found. Those self-conscious efforts to mimic “insurgent” populism by attacking civil servants or goading environmentalists are gone. Instead, Starmer’s speeches now talk more about the long-term national interest, pragmatism, calm and security. Inside Downing Street, he has cracked down on anonymous briefings and, by most accounts, been more assertive about what he wants with his aides. For all its troubles, his government now at least seems a bit more like him.

Although he knows there are risks in elevating the leader of a party with just five MPs as his main opponent, Starmer has decided to do just that with Farage. “If we’re going to have a battle with Reform – a battle for the heart and soul of the country – we’re better off having it now,” he says. “If we’re to win that battle, we have to be the progressives fighting against the populists of Reform – yes, Labour has to be a progressive political party.”

None of this will be easy. Over the last week, he has spent sleepless nights trying to “de-escalate” the conflict raging in the Middle East and promised to raise Britain’s defence spending by another £40bn a year by 2035.

Once inside, he filled black bin liners with rotten food from the fridge and dirty clothes from the floor

Once inside, he filled black bin liners with rotten food from the fridge and dirty clothes from the floor

Investing for the future and diverting money to security may not satisfy voters whose patience with politics has worn so thin. Many will still be tempted by the simple solutions, short-term fixes and three-word slogans offered elsewhere. He’s swimming against a dangerous current that could yet sweep him away.

And he has problems within his own party too. On Tuesday, he faces a mass revolt of possibly more than 100 Labour MPs against plans to cut £5bn from the rising cost of disability benefits. The government is now leaning into further reasonable concessions – offering rebels “a ladder down which to climb” – to prevent the towering Commons majority Starmer won just a year ago being toppled by backbench rage.

Much of the anger is directed at the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, for being too rigid in her fiscal rules. Still more is directed at McSweeney in Downing Street, who some MPs say became too obsessed with chasing after Reform.

But some of it is coming the way of Starmer too. His determination to stop politics venturing too deep into what’s left of his own “real life” can, conversely, make him look remote from other “real lives” and his MPs.

And that’s the paradox about this prime minister. So much of him is this very ordinary family man and yet so many people see him as not just overly serious but out of touch. He loves his wife and children, has real friends and is a “proper” Arsenal fan who enjoys a beer and a curry. He comes from a working-class background, has no time for show-offs and shares the low opinion of voters about a lot of what goes on in politics. All of which should make him more capable of fitting into the contours of his country than any privately educated, pint-posing populist.

Yet he instinctively and stubbornly resists using what is most important to him as “props” for his career. For instance, he saw first-hand the disabilities suffered by his mother and brother. It’s partly why, earlier this year, he intervened to stop benefit reforms that would have frozen payments even for people with the most severe conditions. But rarely – if ever – does he bring these experiences into the way he talks about policy. His family never asked him to go into politics and he doesn’t want their lives moulded into a “brand”, “vision”, “strategy”, “message” or any of those words real people don’t use at their kitchen tables. That is why he has kept his front door shut and his home for his own: he didn’t want the authentic to become synthetic; he didn’t want to let politics inside.

June: The PM sits at his desk in Downing Street with new kitten, Prince

During the election campaign last year, Starmer became almost notorious for his stonewall responses to journalists seeking answers about the private person behind his remote public image. Is he an extrovert or an introvert? “I’ve never really thought about it.” Who’s his hero from history? “I don’t pick heroes.” When did he last get drunk? “The answer is not never, but I cannot remember.”

He hasn’t changed too much in this regard. When I remind him that Tony Blair complained about getting “scars” on his back after a year in No 10, and ask whether he now has some too, Starmer sort of laughs at himself as he ducks the question. “Oh God, you know I don’t do this self-analysis thing very well,” he says.

We finish talking in time for him to get to his flat for a family dinner and Starmer walks me to Downing Street’s front door. But it’s not quite the end of this conversation. An hour or so later he sends a text, saying he thinks the firebomb attack on his home was another instance in his life “when the public and private come into sharp tension”.

For someone who claims he doesn’t do self-analysis, that’s pretty insightful. And, in the end, this “sharp” division between his public role and private self is not only about protecting his family. I suspect the “tension” in him is also the source of the relentless, often ruthless, drive and determination that most people do not see.

Next week will mark his first anniversary behind Downing Street’s front door. Who knows how many more he will have? The odds on him succeeding as prime minister might have got higher over the past year, but so have the stakes. And it would be very foolish to underestimate Starmer just because he keeps so much of his force and power behind his defences, inside.

The paperback of Tom Baldwin’s biography, Keir Starmer, will be published next month (William Collins) £10.99

Photographs by Getty