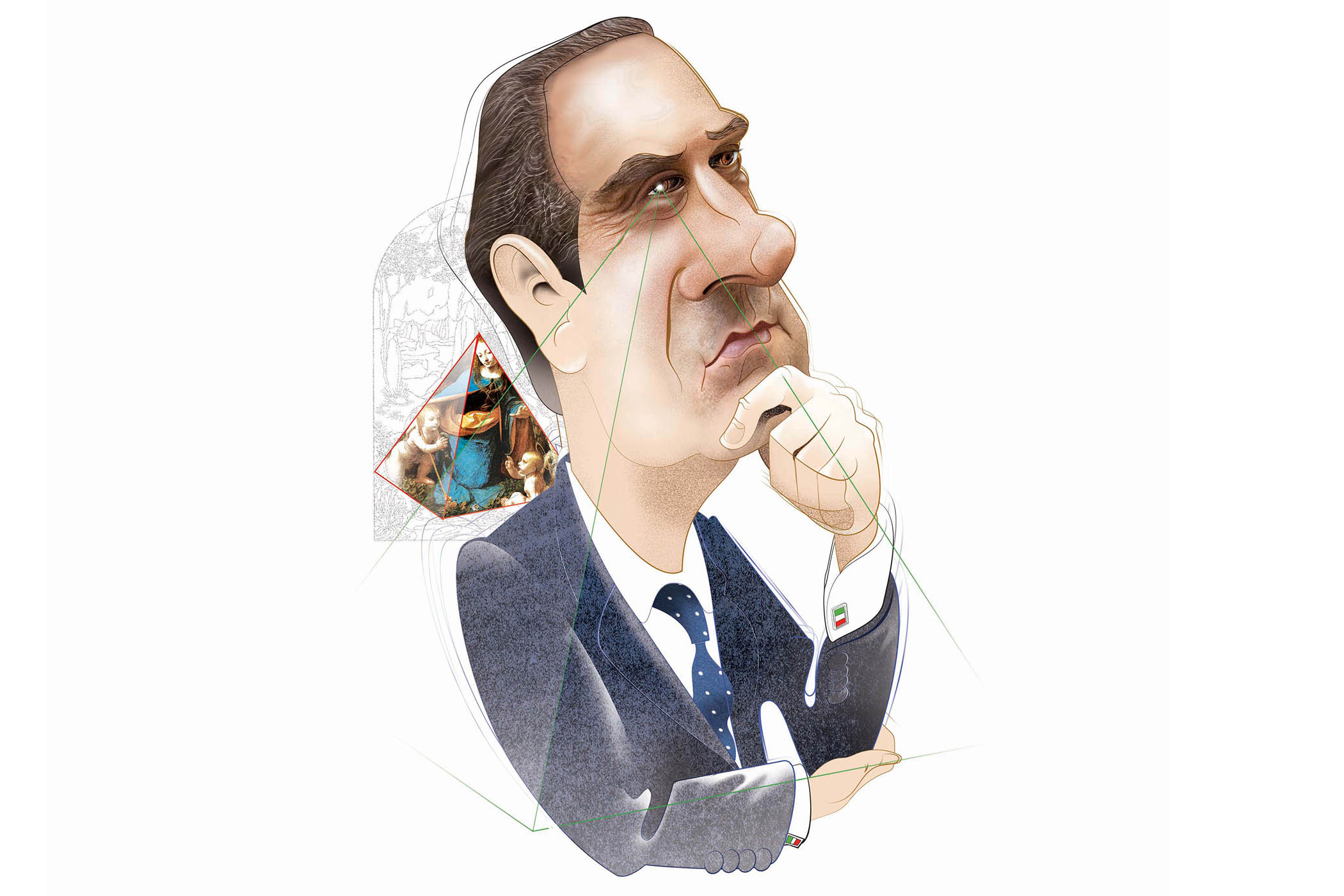

Illustration by Andy Bunday

Money changes things. It doesn’t matter if you are the best of friends or, as in the case of the National Gallery and Tate Britain, merely on good terms; when one side benefits suddenly from a large windfall of cash or a bit of successful prospecting, a relationship can sour overnight.

In London these grand temples of fine art both still rank high on the list for cultural tourism. But the National Gallery, packed with Titians, Monets and Turners, has just pulled off a huge financial coup, netting £375m. It is run by Gabriele Finaldi, a tall, dark, courteous man from unlovely Catford, south London, who has managed to defy the funding crunch in the arts world by securing two vast donations of £150m each. One comes from Crankstart, a foundation set up by Sir Michael Moritz and his wife Harriet Heyman, and the other from the Julia Rausing Trust.

“This is an amazing feat of negotiation and fundraising,” says Alison Cole, a former editor of the Art Newspaper who directs the independent Cultural Policy Unit. “We should all celebrate ambition on this scale. It also presents an exciting opportunity for Tate, as well as the National Gallery, to reassess its buildings and collections policies.”

The question of what Finaldi will do with the money (more has come from anonymous donors) is now crucial, not just for the art-loving public, but also for Maria Balshaw, director of Tate, which includes Tate Modern and galleries in St Ives and Liverpool, who must be welcoming his good fortune with a tightly clenched jaw. Officially, the innovative Balshaw is applauding the news, saying she will work closely with Finaldi to “further the national collection as a whole”. But the land grab has come as the National Gallery and Tate Britain are battling to maintain visitor numbers.

More positive about the prospects for both is the eminent Dutch curator Taco Dibbits, who was talked of as a candidate for the top job in Trafalgar Square in 2015, when Finaldi was picked. He has since risen to the top at Amsterdam’s prestigious Rijksmuseum. “I am very happy for Gabriele,” Dibbits said. “Those big donations from one person are unusual in Europe and there is a chance it might make other donors scale up.”

“He has played a blinder,” suggests another old London friend and rival curator. “This is a triumph really more on the American model. There is an orthodoxy to Finaldi and he is discreet, which donors like.”

Of course big money is good news for the sector, but Tate Britain and the National will now compete not just for punters and high-rolling philanthropists, but for works of art. Finaldi has turned his back, with his customary courtesy, on a long-standing honourable agreement about how to divvy up the collections, with the National Gallery’s roster stopping in the year 1900. Finaldi argues this fin-de-siècle boundary “looks more and more artificial”, explaining to the New York Times that “1900 is a long, long time ago, and we’re very conscious that painting didn’t stop then”. Dibbits, who worked with Finaldi on the Late Rembrandt show in 2015, gets this: “We’ve been doing modern too for some time at the Rijksmuseum. After all, the 20th century is limitless and there is plenty of work to go round.”

It is a breach of understanding that has surprised one former leading curator, who prefers to remain nameless (as Finaldi himself has said, publicly judging other institutions is “just not cricket”). “The choice of 1900 might seem arbitrary,” the veteran says, “but it’s when many scholars agree modern art really begins. And anyway there was always a friendly arrangement whereby any relevant work could be loaned.”

His reputation is for the kind of firmness that can seem fierce

His reputation is for the kind of firmness that can seem fierce

Former BBC arts editor Will Gompertz, now running the Soane, salutes Finaldi for grabbing the nettle: “I felt it was inevitable really. Painting did not stop in mid-sentence in 1900. He is a great leader, I think, generous and knowledgeable.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

For Finaldi, who first visited the National at seven, this is the moment of transformation he has always imagined. “I’m now nearly 60 and I don't think it’s ever looked so beautiful,” he wrote in the Evening Standard last week, revealing his hope to emulate the transformation of the area around Tate Modern.

He is driven by a profound feeling for art. The proof is the sparkle in his eye when he talks to guests about a painting during one of the gallery’s evening events, but also when he pretends to be a pharaoh for a handful of visiting toddlers staring up at Orazio Gentileschi’s The Finding of Moses, a work he saved for the gallery.

At the Courtauld, where Finaldi studied art, he is remembered by fellow students as solid, careful and warm. Former colleagues also speak of him as primarily a family man. All the same, at work he has a reputation for the kind of firmness that can seem fierce.

He was born in Barnet but his Neapolitan father and half-Polish, half-English mother moved to south London to raise the family. In the Finaldi home both the food and the language were Italian, and opera provided the backing track.At Dulwich college, he met and made a lifelong friend of Jeremy Deller, the artist. “We did art history together and even at school he had the bearing of someone much older,” says Deller. “There was a wisdom, or gravitas, to him that is unusual in a 16-year-old. I don’t think the teachers knew what to do with him.”

Finaldi came to run the gallery in Trafalgar Square a decade ago,after a spell in Madrid at the Prado, bringing back his Spanish wife, Marie Inés, with whom he has six children. He had been considered for the National directorship before, when Sir Nicholas Penny got the job in 2008, although was not actually offered it.

Finaldi’s accomplishments as director, leaving aside the saving of various works for the nation, were crowned this spring by the conclusion of a triumphant bicentenary year. Highlights included a blockbuster Van Gogh exhibition and his knighthood in the new year honours list.

There was also a full rehang of the permanent collection and the opening this year of the revamped Sainsbury Wing entrance. Finaldi’s long-term plan, Project Domani, is to redevelop St Vincent House, an office space behind the gallery. Building work costing around £400m is due to start in about a year and will create a home for work that will controversially cross over into the 20th century.

Not everything going on in the shadow of Nelson’s Column has been easy, however. Finaldi arrived during a painful dispute with staff. “It was a bumpy period, but we have moved on,” he has said.

In 2019 an immersive display of Leonardo’s The Virgin of the Rocks did not win universal acclaim. Much worse for him though were the “very distressing” string of protest attacks inside the gallery, in particular a hammer blow to Velázquez’s The Rokeby Venus in 2023. Finaldi has since put protective glass over some of the gallery’s more famous images, which he hates.

He has also had to contemplate falling visitor figures. When the Sainsbury Wing revamp was greenlit it was expected they would reach 7 million, but the impacts of Covid and Brexit caused a drop-off. Finaldi has since argued that well over 3 million “is a huge number of people” and that 4 million is in sight.

His faith in the future may be down to his strong religious belief, which also shapes his taste. In spring 2026 the gallery will host the first British show devoted to the Spanish devotional painter Francisco de Zurbarán, who was commissioned to paint monks, nuns and martyrs by religious orders. One of his favourite works in the gallery is a Zurbarán still life showing a cup and a rose on a silver plate. He loves the way it invites the viewer to pick up the cup and how the objects appear to give off a spiritual glow. “It is all based on his faith; his joy in art and the way he is, his time for people,” says Deller.

Finaldi’s mission is to bring the public together in front of great art in order to understand the past and the present. Even less famous works, he is convinced, “carry meaning and the gallery has to find ways for the modern audience to be engaged by them”.

Gabriele Finaldi

Born 28 November 1965

Alma mater Courtauld Institute of Art

Work Director, National Gallery

Family Married with six children