Scientists have created mini-stomachs in a laboratory for the first time, paving the way for treatments for rare diseases that have received little attention from researchers.

The pea-sized miniature stomachs are being used to test drugs for individual patients, offering personalised medicine for sufferers of serious and life-limiting conditions.

The research, by a team from University College London (UCL) and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), might also lead to better treatments for conditions such as acid reflux, which affects about a quarter of adults in the UK and can increase the risk of oesophageal cancer.

“This is a major step forward and could have implications for more common diseases of the stomach lining, which millions of people suffer from,” said Prof Paolo De Coppi from the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, and a co-lead author of the study.

“We have now been able to test treatments for a very rare gastric condition,” he said. The condition, PMM2-HIPKD-IBD, affects only a handful of children a year, and De Coppi stressed that investigations for treatments were in the early stages.

He is optimistic that the mini-stomach systems will help provide a solution for many diseases but the research team began with PMM2-HIPKD-IBD. The aim was to help some of the children at GOSH, such as Will Balestrini, a 15-year-old who has needed two kidney transplants because of the toll the condition takes on his kidneys.

“He has always had stomach problems but we put it down to other things because we thought it couldn’t possibly be another medical condition,” his mother, Nancy, said.

“It’s nice to know that the families of children born with this condition in the future will have a lot more answers than we did.”

Rare diseases such as Will’s are less attractive for pharmaceutical companies to investigate, since trials are expensive and there are few patients who can benefit from their results.

Stomachs are also one of the least well-understood human organs. A lack of funding is one issue – this research was backed by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, GOSH Children's Charity and the Oak Foundation. Another issue is that animal stomachs are much more different to human stomachs than are their lungs, hearts or kidneys. Mice, for example, have an additional forestomach to store food before they digest it. Macaques produce weaker stomach acid than humans do.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The first breakthrough that allowed scientists to go beyond animal research came in 2009 when Hans Clevers, a Dutch geneticist, proved that stem cells could be used to grow tissue that replicated parts of the human stomach. These Petri dish creations, called organoids, led to several scientific advances, such as new ulcer treatments, but were not able to deal with complex diseases or issues that mean one part of the stomach affects another.

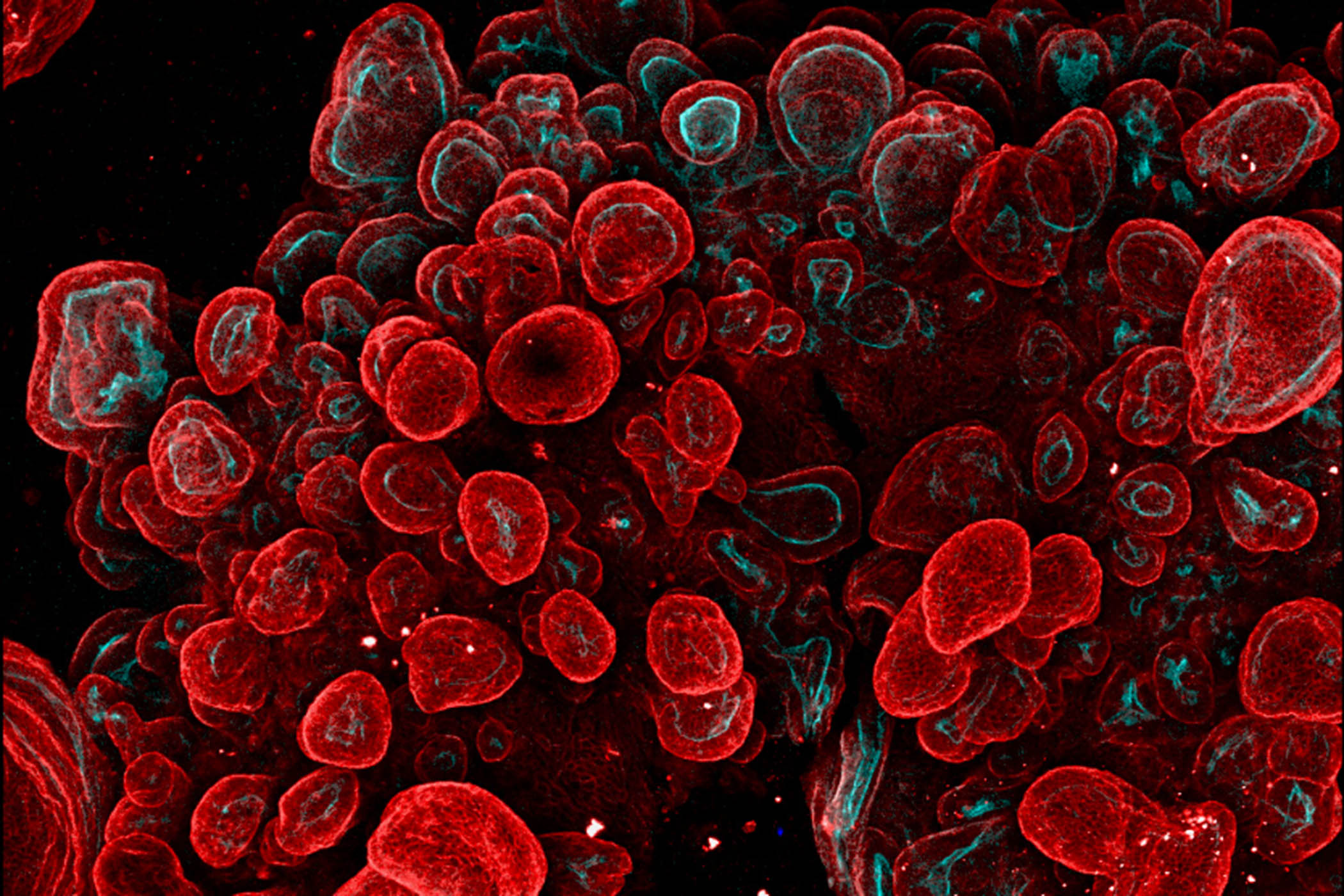

Now the UCL-GOSH team has managed to grow a mini-stomach that, for the first time, combines the key components of a full-sized stomach. In a paper published today in Nature Biomedical Engineering, they describe how they created organoids from the three main stomach regions and managed to assemble them into a single piece of tissue, calling it an assembloid.

It contains the fundic region (the upper portion of the stomach), the body (the central region where food is mixed with acid and enzymes), and the antrum (the lower region that breaks down food).

Dr Giovanni Giobbe, another senior author of the study, said the fact that the mini-stomachs joined together as they grew meant they are much closer to a real stomach than an organoid.

They can even produce stomach acid, and the research team discovered that the three regions communicate with each other, like in a real stomach – for example, by using hormones to signal that another region needs to produce acid.

“They are able to cross talk with each other,” he said. “Organoids alone cannot do this.”

After demonstrating that the assembloid worked, the team grew versions from stem cells of children with PMM2-HIPKD-IBD.

Mini-stomachs grown from patients, including Will, were able to replicate the polyp-like growths on his stomach lining – something that was previously impossible with organoids. As a result, the team can use the mini-stomach to test existing drugs that may have an impact on Will’s condition. De Coppi and Giobbe have begun examining several drugs and are optimistic about finding something effective. And they expect the mini-stomachs to point towards many other areas.

“We wanted to prove that it works on one thing because we have a series of things we want to test,” De Coppi said.

About 15% of adults regularly take proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole or lansoprazole for acid reflux, stomach ulcers or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Yet there are large gaps in clinicians’ understanding of why these conditions take hold.

“It’s a huge problem,” De Coppi said. “We envisage that these systems will allow us to look into even more common diseases to understand how this reaction happens.”

Illustration courtesy of B. Jones, G. Benedetti et al., Nature Biomedical Engineering