Every year since 2008, with a gap for Covid-19, linguist Nicholas Evans has taken a banana boat six hours along the coast of New Guinea to reach a village called Bimadbn. There he spends the next six weeks documenting a previously unwritten language called Nen.

Before turning his attention to New Guinea, the 69-year-old Australian National University professor spent decades immersing himself in Australia’s indigenous languages. It’s for his work in these two spheres, geographically adjacent but linguistically light years apart, that he has now been awarded a medal for lifetime achievement by the British Academy – linguistics’ answer to a Nobel prize.

The first winner of that medal, in 2014, was Noam Chomsky. Chomsky famously emphasised the commonalities across languages, the universal template or grammar that a baby is born with, that allows it to pick up any natural language with minimal prompting.

Evans thinks the Chomskyans are looking through the wrong end of the telescope, and that what defines language is its staggering diversity – the vast span of “engineering solutions” that evolution has found to the problem of human communication.

A language must allow a person to express any idea to another person, but it also has to be learnable by babies. These two constraints drive language evolution, but what nobody yet knows is where the limits of the possible lie. How big is the language design space? Or, to put it another way, how complex or expressive of the minutiae of human experience can a language become, before it becomes unlearnable?

The reason nobody knows this is because it is thought that only about 10% of the estimated 7,000 living languages are well documented. Since 90% of those languages are also endangered, with many of the unwritten ones being at the greatest risk of extinction, Evans has long argued for the need to record them.

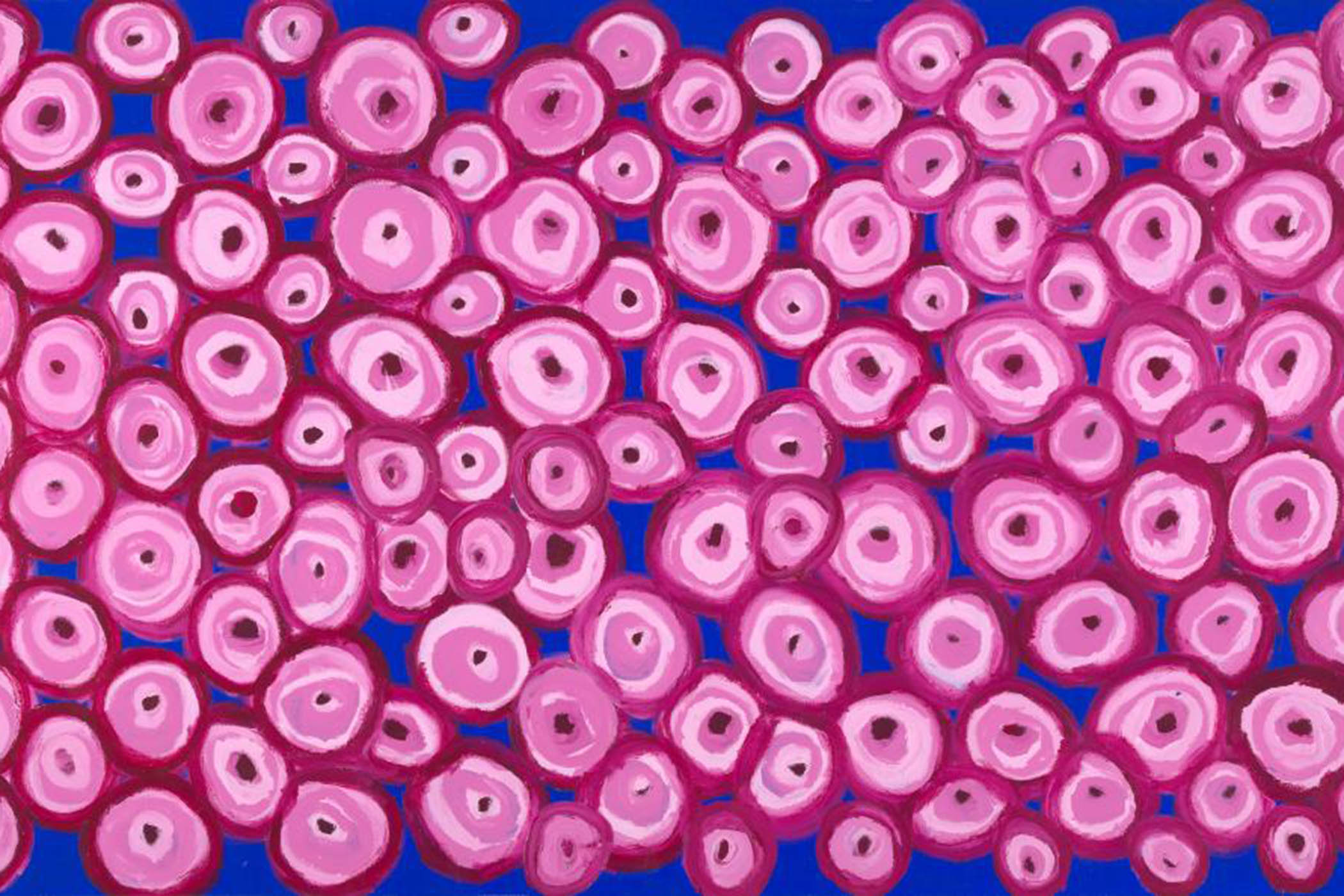

Kaiadilt artist Sally Gabori’s painting Big School of Mullet helped Nicholas Evans solve the mystery of a Kayardild word that meant both ‘hole’ and ‘school of fish’

The linguists who take on that painstaking task are constantly reminded of the ocean of diversity on whose shore they stand. “Almost every new language that comes under the microscope reveals unanticipated new features,” Evans and fellow linguist Stephen Levinson, then director of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, wrote in a landmark 2009 paper questioning the mainstream Chomskyan view.

There is another reason why Evans considers documentation so vital. Language infuses everything we do, so studying it is, he says, “mainlining into the human experience” – past and present.

Related articles:

Both Australia and New Guinea are thought to have been inhabited for 65,000 years, but their history only began to be written down a few centuries ago, by European colonists. Contained within their indigenous languages is an archive of their unchronicled past – all the contact,conflict and migration that moulded those languages – along with libraries of knowledge about the natural environment, and local cultures and religions. This is why Evans calls linguistic fieldwork “the last opportunity for true exploration on Earth”.

Growing up monoglot in an officially anglophone nation, he was vaguely aware of standing at the eye of a linguistic storm. Like other Canberra kids, he would wander in the bush, but he wouldn’t know the names of trees or birds. “You felt very detached from what was around you.”

He found the antidote to that detachment when, in his twenties, he arrived on Mornington Island, north-west Queensland, to do his PhD on the now nearly extinct language Kayardild.

It was evening. The men were spearing fish on the sandbar, but as soon as they returned they started teaching him. “They were grabbing me and saying marrald!, kirrk!, thukand! They were just grabbing me and touching me and saying these words.” It was primal, he says – the way a child learns.

He was soon adopted by the community leader, Darwin Moodoonuthi, and his wife, May, but initially as a father figure. It took them a while to shrug off a legacy deference to his whiteness and hit on the more natural kinship relation. “When they saw how stupid and useless I was, they thought, no, we’d better make you our son.”

In 1995 he published A Grammar of Kayardild, but he soon felt too comfortable in the Australian linguistic milieu, so he crossed the Torres Strait and plunged into a radically different one.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In Papua New Guinea (the country that occupies the eastern half of New Guinea), 10 million people speak more than 800 languages. Many of those languages have fewer than 500 speakers, and most are undocumented, but it’s clear from the ones that are that they are far more different from each other than the languages of Australia. In terms of linguistic diversity, the Papuasphere rivals Eurasia: “Take the whole of Eurasia, from Ireland to Japan, from northern Siberia to Sri Lanka, and shrink it down onto one island,” says Evans.

In some respects the Papuan languages are more diverse than the Eurasian ones. Irish- and Japanese-speakers share a base-10 (or decimal) number system and a seven-day week, and speak in sentences. Papuan number systems range from base-6 to base-27. Yélî Dnye, the ear-poppingly complex Papuan language for which Levinson recently published a grammar, has no concept of calendrical time. And there are languages in the New Guinea highlands whose speakers chain clauses together so that they effectively speak in paragraphs.

Evans, who describes himself as anarchic by nature, loves that this exuberance is the product not of some totalitarian state or academy, but of “the ordinary person doing quite mundane things” – teaching their children, mishearing their elders, bamboozling their enemies.

Many of his Australian informants also speak English, but that’s not the case in Bimadbn, where deciphering Nen is what he calls a “pure code-breaking exercise”. Another linguist, Don Kulick, described that exercise well in his 2019 book, A Death in the Rainforest: “Sound by sound, word by word, phrase by phrase, you gradually acquired it, like a magpie collecting twigs and fluff and shiny objects in the hope of building a serviceable nest.”

This is the way people learned new languages through most of our species’ past. It requires patience and immersion in the life of the community, which means facing the same hardship and risks as the locals. Papua New Guinea is one of the world’s poorest nations. Bimadbn’s inhabitants grow most of what they need, or hunt it with bows and arrows. They get by mostly without electricity or modern healthcare. In the course of his career, Evans has been shot at and chased by crocodiles, and nearly drowned at sea.

A village in Papua New Guinea. More than 800 languages are spoken in the country, some by fewer than 500 speakers

The thrill of working with his teachers more than makes up for the danger. When a verb can take thousands of forms, as in Nen, one useful service a teacher can provide is to pluck out the infinitive – the key to the verbal chaos. But the drudge work of conjugation is only one part of elicitation, or linguistic data gathering. “It’s about getting people to give revealing examples,” he says. “When would I say this? The people who are really good to work with, who may not be literate, are people who give very good contexts.”

Since you need many contexts, you need many informants. Evans learned a lot from watching girls play string games in Bimadbn – a local tradition somewhere between amusement and artform – and from sharing the men’s daily bath at the river. This offered unexpected teaching moments, as when a tree snake pounced on a frog and he learned, from the men’s commentary, when “swallowing” became “swallowed”.

The Kaiadilt artist Sally Gabori, whose work Evans promoted before she became famous, helped him solve another mystery. The Kayardild word malji means both “hole” and “school of fish”. He couldn’t work out why until he saw a painting of Gabori’s depicting a school of mullet as a mass of circles, or holes. “It’s when they come to the surface and their mouths just sort of let out these little bubbles and that’s how you see them,” she explained.

Being so immersed in his informants’ lives, he has occasionally been drawn into their struggles. In the 1990s, when the indigenous inhabitants of Mornington Island were trying to get their ownership of the land legally recognised, he acted as an expert witness. There was a meme circulating at the time, that indigenous people don’t own the land, the land owns them. He could point to his grammar of Kayardild and say it wasn’t true. They had the same concept of ownership as everyone else, and the word – actually the suffix – to prove it.

The hardest part of his job remains translating the thought world of one language to that of another, he says, because even if humans inhabit the same broad reality, different languages crystallise different aspects of that reality. Evans is reminded of this every year when he travels to Bimadbn. As the banana boat bobs past the mangrove swamps that screen the New Guinea coast, it occasionally strays into the range of Australian telecoms and a message pops into his phone, in which Domino’s promises to deliver pizza anywhere. “I haven’t tested them yet,” he says.

Photographs by Jimmy Nébni, courtesy of the Estate of Sally Gabori, Alamy