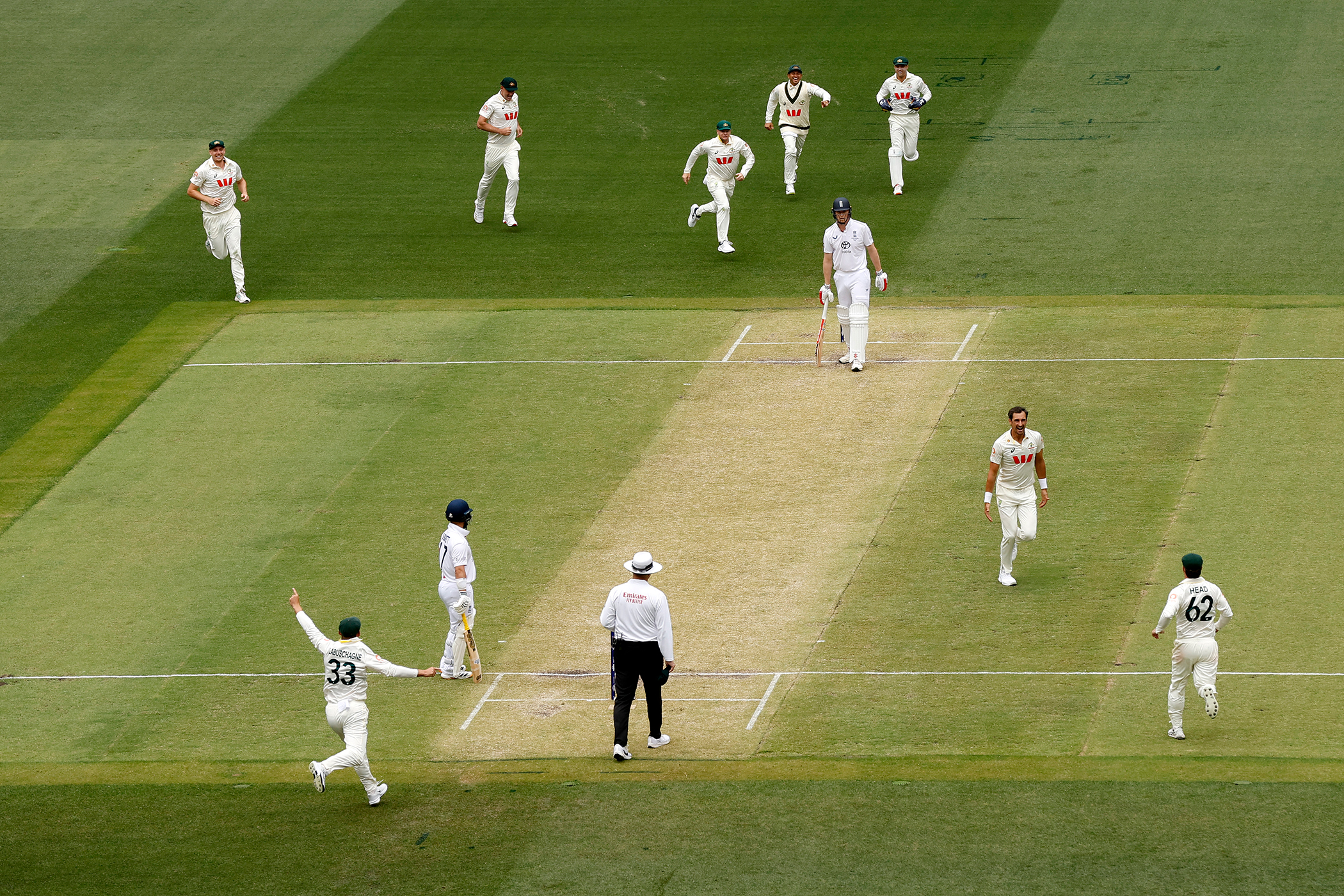

No country has lost more Test matches than England. To give them credit, they keep finding new ways. The old, desperate, backs-to-the-wall, fingernails-on-the-windowsill defeat is a thing of the past; the new, expansive, good-for-cricket, morally-victorious loss is now de rigueur. But even by this standard, England’s surrender in Perth will go down as a disaster.

At lunch today, the First Test was firmly in England’s grip. By tea, it had been dumped in Australia’s lap. England lost nine wickets for 105 in a 118-ball, as though trying to win the Ashes on net run rate. We had been promised Bazball with brains this summer; we got instead a newly-lobotomised version.

Enter Travis Head, in the scenario for which he is tailored – a smallish total, licence to attack, pace on the ball. With the Test in the offing last week, his coach Ryan Harris was interviewed. Yes, Travis was conscious he hadn’t made runs for a while. No, he was fine, just working on a few little things in the nets. It sounded like the description of someone pottering at home doing a few odd jobs. With a similarly laconic and unfussy air, he now biffed and boffed to a thirty-five-ball half-century, and the job was virtually done.

A six to third man off Carse, a six to long leg off Wood, four fours in an over from the flagging Stokes, and Head was away. So disciplined yesterday, England lost all semblance of sense, shape or plan. Bowlers who had appeared unplayable just 24 hours earlier were put to the sword. Jofra Archer was slapped impudently over his head. Gus Atkinson was reduced to bowling bouncers to clear the batters’ heads – which were duly called wide.

Head rampaged to the second fastest Ashes hundred – at 69 deliveries, it was two balls faster than Roy Fredericks’s madcap romp at the WACA half a century ago. The effect was infectious. Jake Weatherald basked in his South Australian mate’s glow; Marnus Labuschagne repented his strokeless defiance of Friday, drawing to leg side to swing for the bleachers.

Nobody would have been happier than Perth Stadium groundsman Isaac McDonald, who before Head’s innings had seen thirty wickets fall in 677 deliveries. There was nothing wrong with his pitch; there had never been anything wrong with his pitch. There has been some fearfully frivolous and self-indulgent batting, with England responsible for… ahem… the lion's share.

At lunch today, the First Test was firmly in England’s grip. By tea, it had been dumped in Australia’s lap. England lost nine wickets for 105 in a 118-ball, as though trying to win the Ashes on net run rate. We had been promised Bazball with brains this summer; we got instead a newly-lobotomised version.

Enter Travis Head, in the scenario for which he is tailored – a smallish total, licence to attack, pace on the ball. With the Test in the offing last week, his coach Ryan Harris was interviewed. Yes, Travis was conscious he hadn’t made runs for a while. No, he was fine, just working on a few little things in the nets. It sounded like the description of someone pottering at home doing a few odd jobs. With a similarly laconic and unfussy air, he now biffed and boffed to a thirty-five-ball half-century, and the job was virtually done.

A six to third man off Carse, a six to long leg off Wood, four fours in an over from the flagging Stokes, and Head was away. So disciplined yesterday, England lost all semblance of sense, shape or plan. Bowlers who had appeared unplayable just 24 hours earlier were put to the sword. Jofra Archer was slapped impudently over his head. Gus Atkinson was reduced to bowling bouncers to clear the batters’ heads – which were duly called wide.

Head rampaged to the second fastest Ashes hundred – at 69 deliveries, it was two balls faster than Roy Fredericks’s madcap romp at the WACA half a century ago. The effect was infectious. Jake Weatherald basked in his South Australian mate’s glow; Marnus Labuschagne repented his strokeless defiance of Friday, drawing to leg side to swing for the bleachers.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

How, then, to explain Bazball’s diminishing returns? It succeeded initially, of course, by being so disruptive – including, in 2023, of an Australian team that had built its cricket on productive partnerships and austere lengths. But if not passe, it has become predictable.

Much has been made of England’s ‘throttling down’ recently, from the palmy days of 4.7 an over to the relative sobriety of 4.3. But this is a species of delusion, as though scoring rates are something England set alone, in the manner of a cruise control, rather than them also being a function of other teams’ bowling and fielding. The fact is that the word is out. Opponents know what England will do, it is just a question of when they will do it.

There had in the morning been a brief intermission of relatively sensible cricket. England kept its score ticking efficiently. Hints of desperation crept into Australia’s cricket. In the tenth over, they twice gave away needless overthrows, the batters Ben Duckett and Ollie Pope being well home. At the break, the visitors were 99 ahead with nine wickets in hand. Lunch would have been toothsome.

An anonymous presence so far, however, Scott Boland again demonstrated his knack of backing into the limelight, nudging his line a little wider, bringing his length back a touch. But honestly, there are spells of bowling and passages of play in Test matches that one simply rides out. Last year, we learned, runmaking here grows considerably easier past the forty-over mark. In the next quarter hour, England gave themselves no chance of finding this out.

Duckett, Pope and Brook were all guilty of playing at balls they could have left. Pope was almost not going to be satisfied until he nicked one; Brook’s bat is like Lancelot’s sword one minute, Quixote’s lance the next. When Starc bowled Root through an expansive drive, England had lost four for 10 in three overs. The ball after Stokes nicked off, Atkinson aimed a wild drive and missed. What was he thinking?

We knew what Steve Smith was thinking. Sometimes in a Test match, in fact, the play can seem to condense around an incidental moment. Here we were just over half way through the second afternoon. Australian bowlers were on top. England were seven for 112, with two tail enders at the crease. But, huh? At the solitary wide slip, Smith was semaphoring fielders hither and yon. By the time he’d finished disposing his forces, six fielders were on the fence, leaving the broad expanse of the field looking almost deserted. But Smith’s reasoning wasn’t far to seek – England are as wedded to attack as the Light Brigade were committed to charging.

It might well have been a tactical error. These tailenders, Atkinson and Carse, did indeed keep coming – the field notwithstanding, they wellied 50 in 5.4 overs, with Atkinson taking two sixes from the magnificent but tiring Mitchell Starc. But you also knew that this could not last. With a run in every direction, Carse tried to ramp and was caught at the wicket, Archer then Atkinson surrendered their wickets, and the stage was set for the evening batting matinee.

Australia's one concern will be Usman Khawaja, who tried to field but dropped Jamie Smith’s low edge at slip, then was too earthbound to collect Smith’s flying edge. Halfway through the next over but one, the veteran walked off, slowly and gingerly, looking down, as if transfixed by the sound of his own footsteps. There was the slightest smattering of applause as Khawaja crossed the boundary, but that Sydney farewell has never looked further away.

The irony is, of course, that Khawaja could not have aggravated his back strain at a better time. His job was entrusted to Head, Head trusted to fortune, and 141.1 overs was all it took for Australia to take its first step to retention of the Ashes. When Head finally holed out with 13 runs required, English fielders in the vicinity converged on him to offer congratulations. A very generous gesture; almost as generous as gifting this Test to their hosts.

Photograph by Cameron Spencer/Getty Images