This article first appeared as part of the Daily Sensemaker newsletter – one story a day to make sense of the world. To receive it in your inbox, featuring content exclusive to the newsletter, sign up for free here.

Jury trials are to be scrapped in cases likely to result in a sentence of under three years, in a bid to reduce a backlog in the crown courts.

So what? This is one of the biggest shakeups in generations. Critics say it imperils an ancient and uniquely British right. The justice secretary David Lammy says it is necessary to save the court system from collapse. The truth is somewhere in between, as the policy

•

could make trials less fair; but

•

affects fewer than 3% of criminal cases; and

•

is unlikely to make a significant dent in the backlog.

Logjam. The crown courts have a build-up of 78,000 cases, up from 33,000 before 2019. It is predicted to rise to more than 100,000 by 2028. Covid is the main culprit, but it is also a symptom of a crumbling system subject to years of deep budget cuts. The increasing complexity and duration of trials is another factor.

Justice delayed. People charged with serious crimes today may not have their cases heard until 2030. This means long waits for victims and suspects, many of whom are held on remand, which contributes to overcrowding in prisons.

Justice denied. Some innocent people may plead guilty in the hope of immediate release, according to the prisons and probation ombudsman. Delays can also lower the chance of conviction, as witnesses forget key details over time. This is a particular concern in rape cases.

By halves. Only 15,000 cases are tried by a jury each year, which will be reduced to 7,500. Magistrates and new “swift courts” with a single judge will deal with the others.

In the weeds. Juries will no longer decide assault, non-violent theft and most drug cases, as well as complicated fraud and financial trials. The practice of letting defendants elect to be tried by a jury rather than a judge will also end. The sentencing powers of magistrates will also be increased from 12 to 18 months to allow them to take some crown court cases.

Striking a balance. These changes are less bold than an earlier plan to end jury trials in all cases except murder, rape and manslaughter. But they still go further than the recommendations made earlier this year by the retired judge Brian Leveson.

Impact. The changes will reduce the workload of crown courts by an estimated 20%. But it may increase the labour of magistrates, who face their own record backlog of 361,000 cases.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Austerity hurts. Investment would have a greater impact. More than half of the courts in England and Wales were closed between 2010 and 2019. Meanwhile legal aid was cut by 28% from 2012 to 2022. This caused a sharp rise in defendants without representation. Their trials can take twice as long and weigh heavily on court time.

Ancient history. The right to be tried by “12 good men and true” is a principle that stems from the Magna Carta of 1215. Juries are imperfect but research shows that they result in fair and efficient outcomes.

Architect’s history. Lammy was against restricting jury trials when he was in opposition. In 2017 he conducted a review for David Cameron which concluded that juries “act as a filter for prejudice”. In 2020 he wrote that they were “part of the bedrock of our democracy”. This week he said changes were necessary to preserve the practice of trial by jury.

Backlash. The Criminal Bar Association and the Bar Council say there is no “real evidence” they will fix the logjam. Keir Monteith, a leading King’s Counsel, says they will “create further unfairness and miscarriages of justice for black and minority ethnic defendants”.

Sympathy of crowds. Unlike judges, juries can acquit defendants based on conscience, even when there is ample evidence that they broke the law. Prominent examples include anti-war demonstrators and civil servants who leak information out of public interest.

What’s more… This is particularly relevant in an era when protest and civil actions have been increasingly criminalised. Juries have recently acquitted Palestine Action, Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter activists, who may now be tried by judges instead.

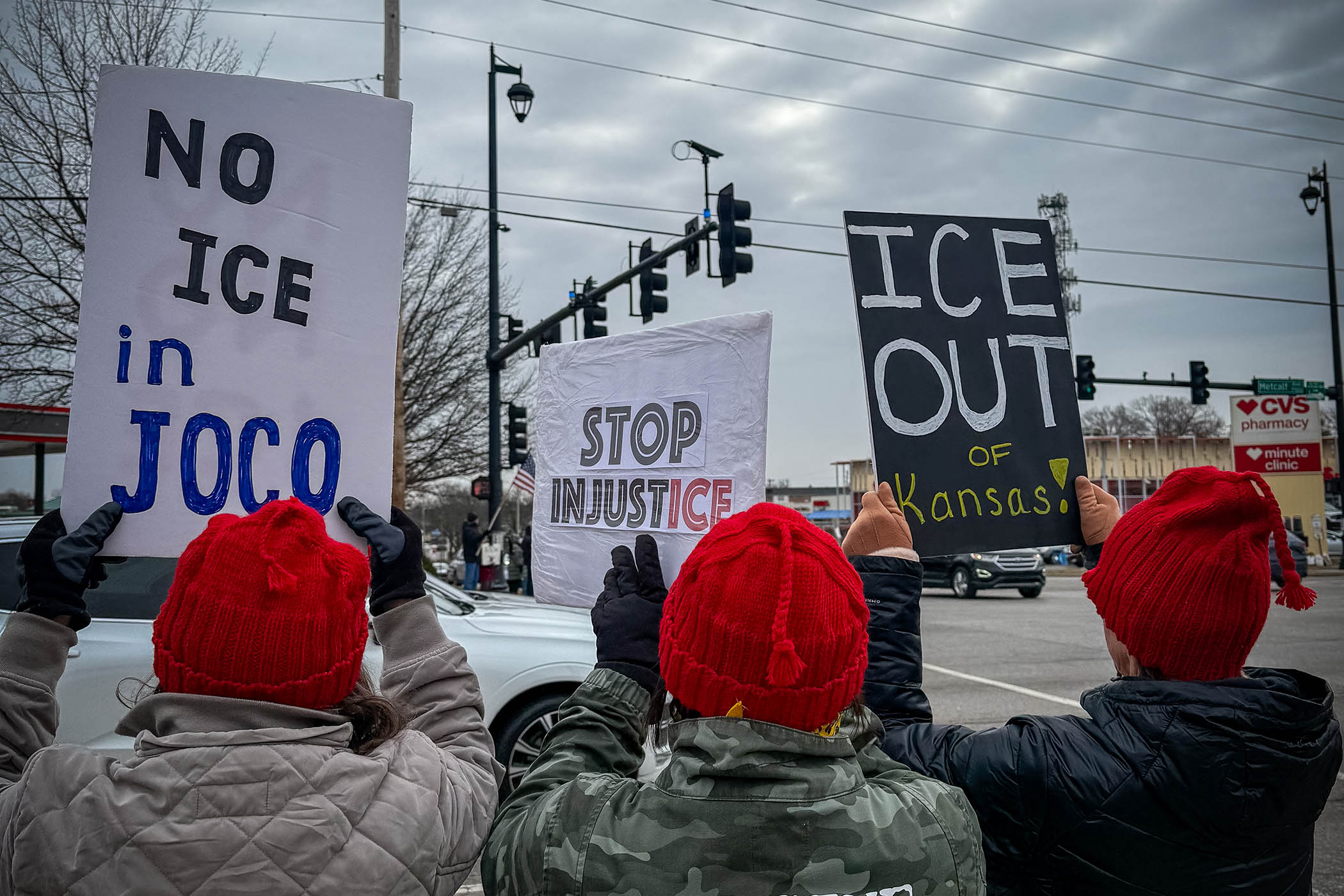

Photograph by Wiktor Szymanowicz/ Future Publishing via Getty Images