It was just a little jump, one of dozens that Melanie Reid had made in 30 years as a keen amateur equestrian. But this one went disastrously wrong. When her husband, Dave McNeil, was told by a doctor later that day that his wife had fallen from her horse, breaking her neck and lower back, and would never again walk unaided, his reaction was natural for a blunt Glaswegian newspaper photographer. “Oh for fuck’s sake,” he said.

Two lives were suddenly upended. Reid was an award-winning 52-year-old journalist; McNeil was 12 years older and easing down after a successful career. Dougie, a son from Reid’s first marriage, was at university and they had finished work on their adored 300-year-old cottage in the Stirlingshire wilds of the Trossachs. These should have been the golden years. Then everything changed.

McNeil went home and wept uncontrollably, literally howling at the moon. “I thought I was a tough guy because I’d done some really hard jobs with Glasgow criminals,” he later said. “I thought I was pretty inured.” Then, when the tears and rage passed, he realised that this was what they meant by “for better or for worse”. Over the following years, until he became the one who needed a carer, he was Reid’s rock.

Her accident and slow recovery became their biggest story, told on Saturdays until 2024 in the Times in what was called Spinal Column, and then for the past year in The Observer. Reid composed it at first on a Dictaphone, then by jabbing at an iPad with the only two fingers that still worked. She said it was like being a war correspondent, reporting from the front line of her body. And every scribbler needs a great snapper.

When she came home, they had The Conversation. “You can leave if you want to,” Reid told her husband. McNeil was a big character, universally loved. She didn’t want him to be stuck with “a lump of meat”. McNeil gave the once Amazonian woman he’d fallen in love with a robust response. “Don’t be so bloody stupid,” he said. Ten years later, in a joint interview, he added: “If I didn’t like you, I’d have been gone in a shot.”

She called him a “flawed saint and sacrificer-in-chief”. McNeil was not a natural caregiver but he learned to adapt, to abandon his natural spontaneity and set smaller goals. Reid wrote honestly about his failings, especially his technophobia, and his fears that she might one day fall from her chair and he wouldn’t be able to pick her up. Yet she also wrote of love and laughter. It was a column full of life and he was a willing stooge and sidekick. “You can write anything you like about me,” he told her.

“He loved it because he was so vain,” she said. For someone used to being the centre of attention, he admitted hating that the first question he was now asked in the pub was “How’s Melanie?” He was upset by only one column, she said, when she pondered what a great lesbian she could have made.

‘The key to Dave was that he wanted to be happy. His great talent was to make people laugh’

‘The key to Dave was that he wanted to be happy. His great talent was to make people laugh’

Melanie Reid

David McNeil was born in Glasgow in 1945, the son of a marine engineer. He was an enthusiastic member of the 108th Partick District Boys Brigade, playing the pipes for them and for the Red Hackle Pipes and Drums, a grade 1 band in Govan. Bagpipe music remained a lifelong love.

After school, he trained as a commercial artist with an advertising agency. Told by his boss that the future lay in photography, he got a place with John Stephens Orr, then regarded as Scotland’s finest portraitist, working for a guinea a week from the studio off Sauchiehall Street where he learnt his craft. One job was to retouch the glass plates using a soft pencil to remove wrinkles. “I was a kind of plastic surgeon,” he said.

He left after three years to run his own studio and was later official photographer for his beloved Rangers FC. He became chief photographer at the Sunday Mail, covering anything from fashion shows in Paris to Wimbledon finals to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. He was one of two photographers stationed near the altar of St Paul’s for the wedding of the Prince and Princess of Wales in 1981, responsible for supplying pictures to the world.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

With his first wife, Liz, he had a son, Stephen, and a daughter, Gillian. He was the Sunday Mail’s picture editor when he married Reid, a colleague on the paper, in 1996. Their guests were kept lively by the reigning world champion piper. McNeil loved rural life, becoming a skilled drystone dyker as well as building a nine-hole golf course with friends on their land overlooking the Campsie Fells.

“The key to Dave was that he wanted to be happy,” Reid said. “His great talent was to make people laugh. He was like the Pied Piper: he drew people to him with his outrageous humour. And so, even though we had this awful setback, he rose to it in a way that lots of people couldn’t.” It was aided by frequent trips to the pub, or “choir practice” as he called it.

The enforced solitude of the pandemic affected a man who so enjoyed company, and there was a cognitive decline. In 2023, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. In her final Times column, Reid wrote: “Now it’s time to look after Dave, as he looked after me… After the sacrifices he has made for me, the care he has given and the worry I have caused him, it is time to reciprocate.”

He was addicted to journalism to the end. Reid said that in his final days he still watched Sky News nonstop, critiquing the coverage of the stories of the day.

David McNeil, photographer, was born on 30 November 1945, and died on 17 February 2026, aged 80

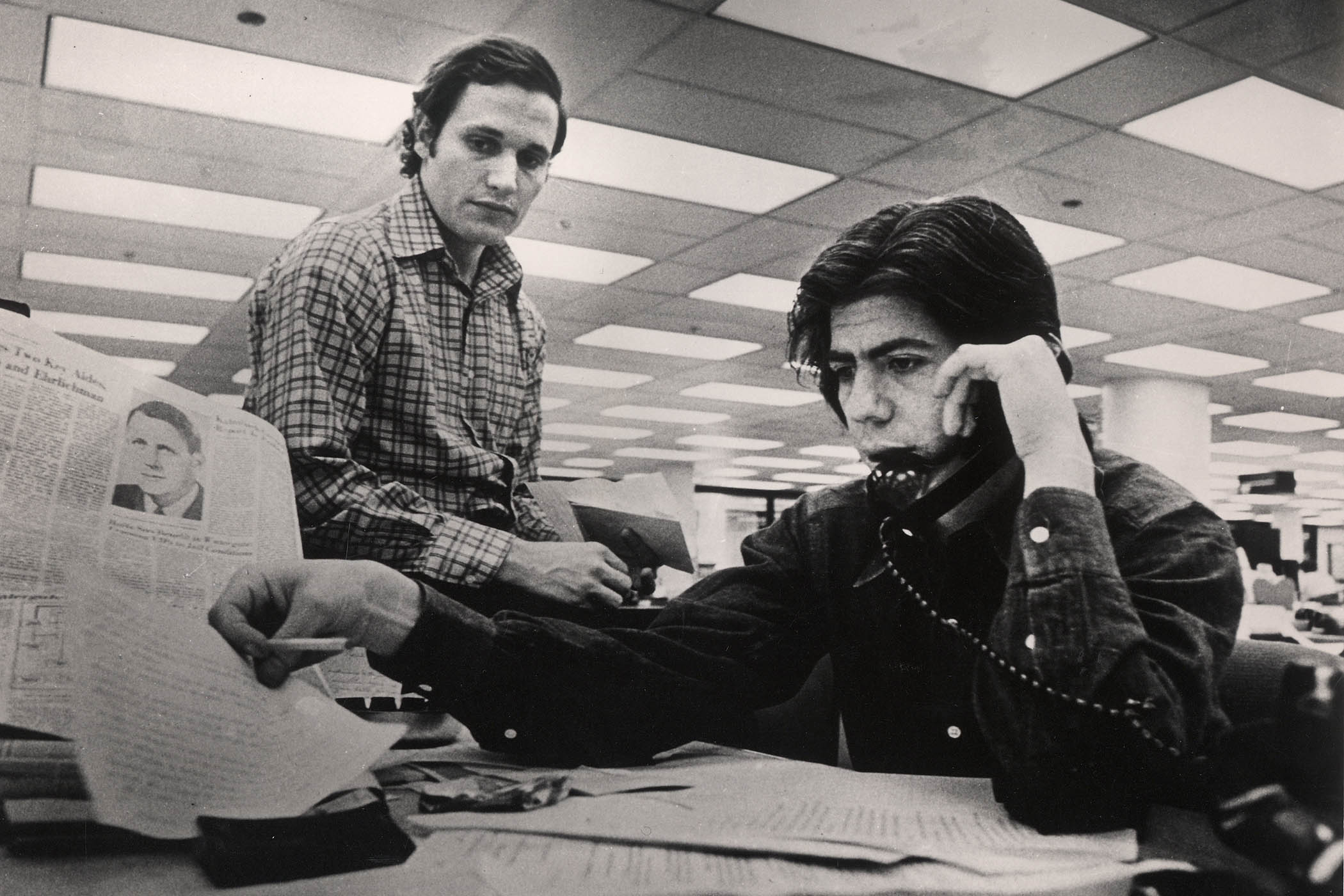

Photograph: family handout